(October 19, 2024) What inspired Ruchit Garg to quit his job at the Redmond Headquarters and return to India to set up a social enterprise for small holder farmers? Especially when Garg, who grew up struggling financially, actually made it to the Holy Grail of tech jobs. It was the desire to make a change at the bottom of the pyramid that took the young boy who would sneak into his local library in India to read the Harvard Business Review, to actually being featured in it himself. In March 2023, the Global Indian, who is the founder and CEO of Harvesting Farmer Network, was invited discuss financial inclusion for smallholder farmers at Harvard University.

Humble beginnings

Ruchit Garg lost his father when he was young, and the family had only his mother’s meagre earnings on which to survive. He was born in Lucknow, where his mother worked as a clerk for the Indian Railways Library. Since the family couldn’t really afford books, the young boy would sneak into the library to read. The library was well stocked, however, and he read a wide range of books and magazines, including the Harvard Business Review, which he loved.

Ruchit Garg, Founder and CFO, Harvesting Farmer Network

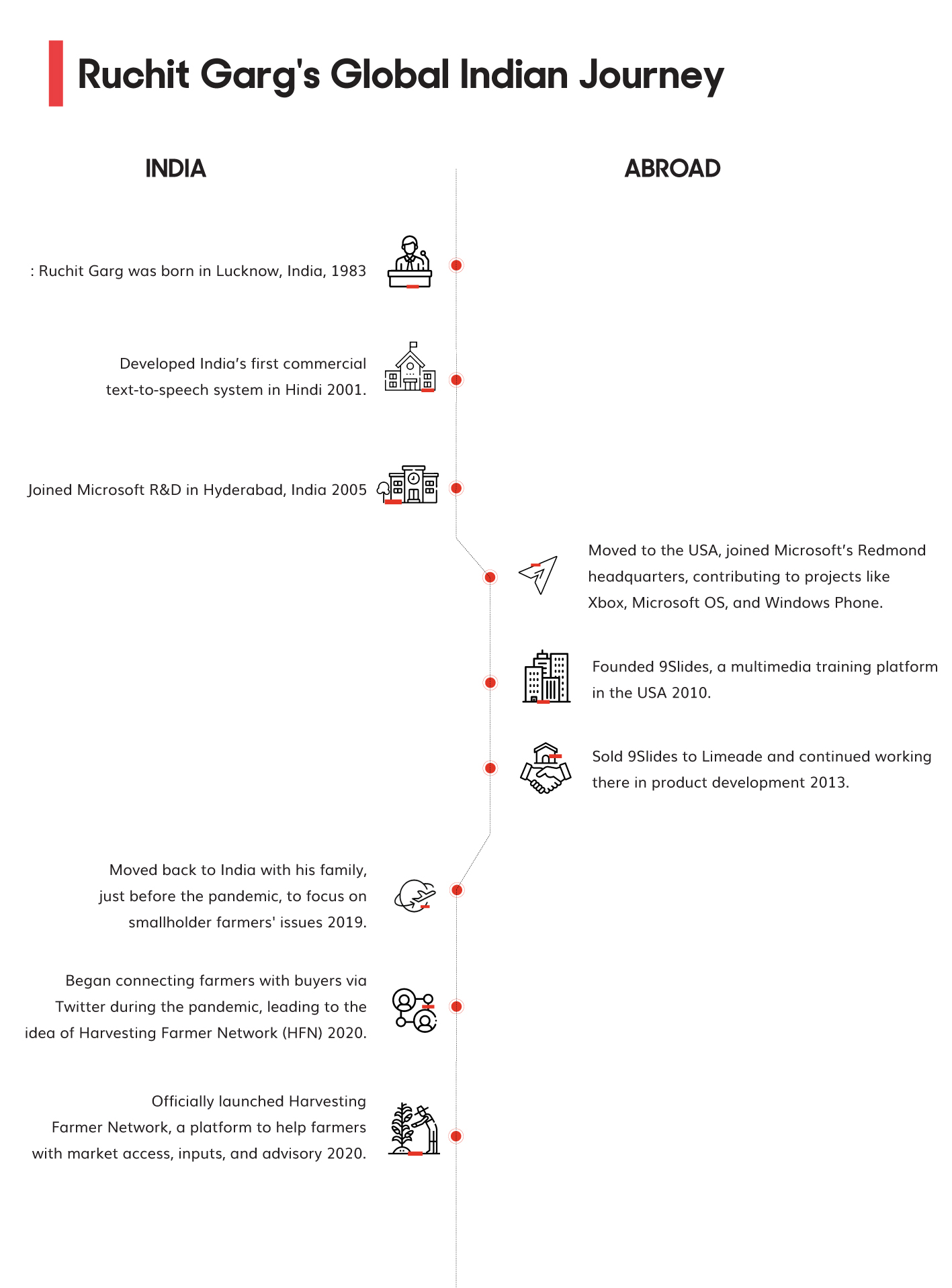

“I grew up in Lucknow, then West Bengal and back to UP where I did a master’s in Meerut,” Garg said. He loved coding and computers and went on to create India’s first commercial text-to-speech system in Hindi, back in 2001, when he was part of a young company. From there, in 2005, he went to Microsoft R&D in Hyderabad and later moved to Redmond, Washington where he helped build XBOX, the Microsoft OS and the Windows Phone.

There was only one problem. “I got bored,” Garg confessed in an interview. “I felt like a misfit there. I always wanted to start a business.” At the time, he was also seeing the startup economy boom in the US, and he decided it was now or never. He founded 9Slides, a multi-media traning platform which allowed business to create, publish and measure their training content on any device. The company was eventually acquired by Limeade, where he worked in product development for two years.

A change of heart

“I saw some recognition and everything that comes with selling a company,” Garg said. “But I realised it’s also not worth it to me, to build something with a solely monetary focus. Obviously, you want to build a hugely successful company, but which can also help people at the bottom of the pyramid,” he says. He recalled his grandfather, who was a farmer in India and the hardships that small hold farms continue to face.

It’s not worth it to me to build something with a solely monetary focus. Obviously, you want to build a hugely successful company, but which can also help people at the bottom of the pyramid.

When he began in 2016, there were 480 million small holder farmers in the world. In 2024, there are roughly 500 million, and they continue to make up a large portion of the world’s poor, who live on less than $2 per day. In contrast, the food agriculture industry is worth trillions of dollars, and small holder farms produce about 80 percent of the food consumed in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. This was one part of the picture that gave him pause. The other was the number of people who go to bed hungry every night – according to the WFP, the number is around 783 million people, that’s roughly 1 in 10 of the world’s population. “Unless we fix the problem, it’s going to be bad for the human race as a whole,” Garg remarked.

Smallholder farmers are central to his solution. Apart from producing the majority of food consumed in large parts of the world, they also reduce dependency on imports and help stabilize local food prices. Many smallholder farms sell their produce at local markets, creating a supply chain that benefits local vendors, transporters, and other small businesses. By purchasing seeds, fertilizers, and farming tools locally, they also help sustain agricultural input markets. They might be small, but they play a crucial role in providing food security for their communities by ensuring a consistent, localized food supply, which is particularly vital in rural areas where larger commercial farms might not operate.

Bridging the gap with tech

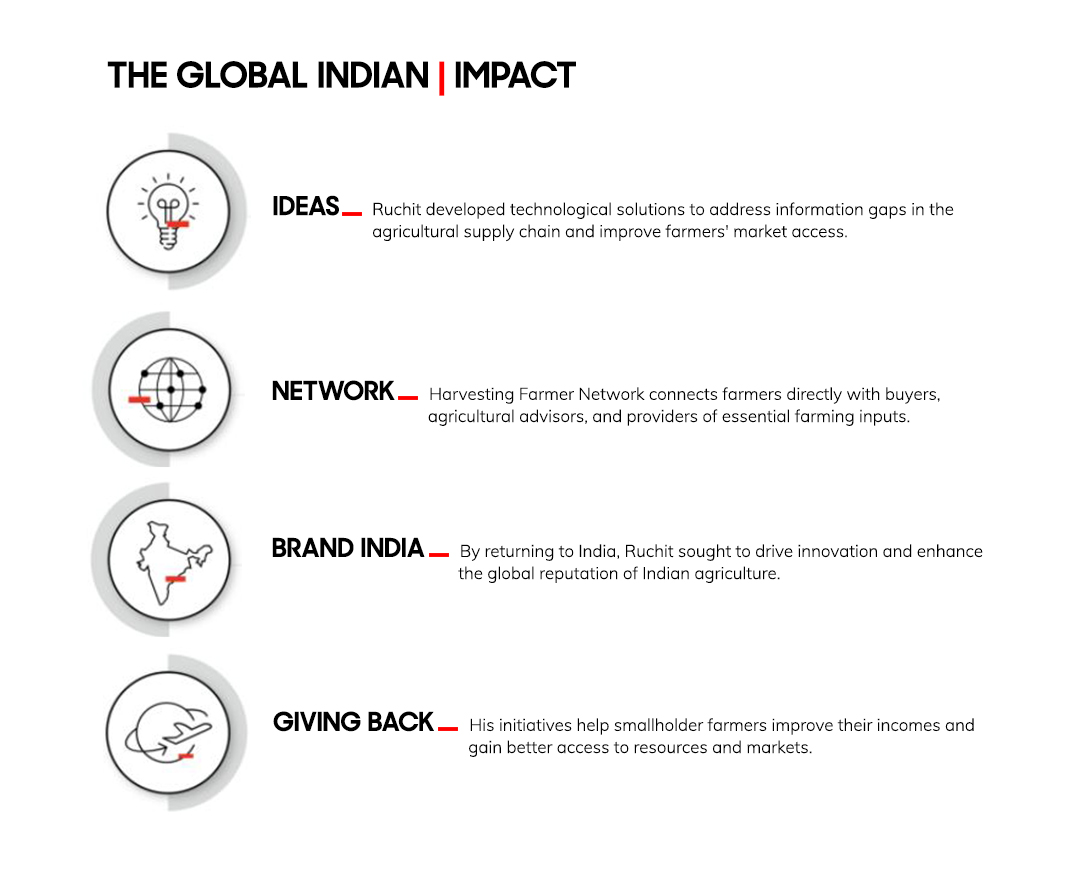

Despite these contributions, smallholders face challenges such as limited access to finance, quality inputs, and market connections, which makes it difficult for them to scale operations or achieve consistent productivity. So, Ruchit Garg began studying these issues and found there were fundamentally three problems. “Access to market, access to inputs like seeds and fertilizers and access to financial instruments like insurance and so on,” Garg explained. “From my perspective as a data tech guy, this can all be seen as information asymmetry; there is a gap between small holder farmers and everyone else in the value chains.” There were lots of companies to give loans to farmers, but it was hard to figure out where the farmer is exactly, what his networth might be or how much crop he produces. “If we could match, make it easier, affordable and timely and available to stakeholders, we could solve a lot of problems.”

Could cutting-edge tech be integrated into the age old practices of smallholder farms? Digital tools are transforming smallholder farming by connecting farmers directly to buyers, reducing their dependence on middlemen. Precision agriculture, including IoT sensors and mobile apps, helps farmers manage irrigation, monitor soil conditions, and predict weather patterns, which boosts yields and cuts costs. India’s investment in agri-tech reached $1.7 billion between 2014 and 2019, showing the sector’s growth potential. However, issues like poor connectivity and digital literacy still limit broader adoption, something Garg’s Harvesting Farmer Network is actively addressing

Moving back to India

Shortly before the pandemic hit, Ruchit Garg decided to move his family back home. He was travelling a lot for work, doing around one international trip every month from California to Nigeria, Kenya and to Europe. Being in India made sense and he would have access to the huge number of small holder farmers in Asia. “Also, my kids were growing up and hadn’t really seen India, I thought it would be a good time for them to move back and also be near their grandparents,” he said.

As soon as the move happened, though, the pandemic struck and the world went into lockdown. Garg was also reading news about farmers throwing away produce and feeding it to cattle because they couldn’t transport it to markets and to buyers. Again, the problem seemed to be an information gap. Garg got on Twitter and began linking farmers with buyers, and immediately, calls started pouring in. There were cases when farmers had huge orders for thousands of kilos which they could not transport because of pandemic restrictions. “I would call the local bureaucrat and arrange for the person to be given a pass. I also worked with the Indian Railways. They were also very cooperative, they even offered to arrange a special train for me. It was a community effort and I found myself at the centre of it,” Garg recalls.

How it works

Simply put, Harvesting Farmer Network describes itself as a “mobile marketplace,” which collaborates with offline centres to help farmers at every step of the growing process, from seed to market. Driven by data, intelligence and technology, HFN establishes digital and physical connections with farmers, providing them with access to inputs (seeds, fertilisers, equipment etc), finances and to buyers, as well as with expert advisory and better pricing. HFN reportedly has 3.7 lakh farmers in its network and covers 948,043 acres of land.

Farmers can also get help on call, and HFN has linked up a network of agronomists and advisors to give them scientific and reliable advices. What’s more, this advice is available in local languages. It also helps to sidestep the middlemen and connect farmers directly with buyers, helping generate better value and revenue for farm produce, using a tech-driven, integrated supply chain.

Follow Ruchit Garg on LinkedIn.