(June 20, 2023) Growing up in a small farming community in Raipur, life was tough for Dr Sanjaya Rajaram and his family. Having seen stark poverty in central India’s rural heartlands, Rajaram had seen the ugliness of stark poverty. It led him to dedicate his life improving the lives of smallholder farmers around the world. The World Food Prize in 2014 was an acknowledgement of decades of scientific work – Dr Sanjaya Rajaram, who served for over 33 years at the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) in Mexico, developed more than 480 wheat varieties, leading to an increase of over 200 million tons in worldwide wheat production.

Humble beginnings

Rajaram was born in 1943 in Raipur, the same year, incidentally, that the CIMMYT was founded in El Batan in Southern Central Mexico, with its nascent programme headed by the legendary Norman Borlaug, known as the father of the Green Revolution. Borlaug’s work would bring him to India to spread the word, resulting the Green Revolution led by MS Swaminathan, with whom Rajaram would also work. Rajaram studied genetics and plant breeding at the Indian Agricultural Research Institute in New Delhi, during which time he worked with MS Swaminathan. Years later, Swaminathan would also be on the World Food Prize (instituted by the Nobel Peace Prize) jury that selected Rajaram as the 2014 winner.

“He is known for his genuine concern for farming and farmers,” Swaminathan said at the time, about Rajaram. “He is a worthy successor to the legacy of Norman Borlaug and was selected for his outstanding work in the improvement of wheat crop and wheat production in the world.”

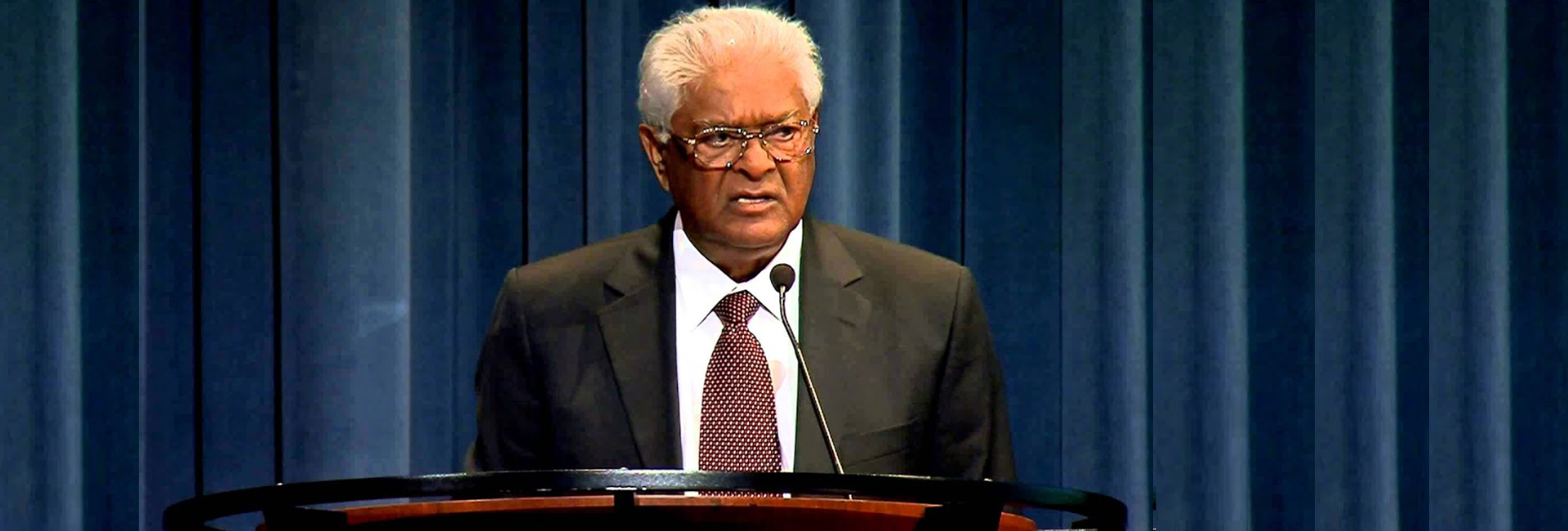

Rajaram, not always given to talking about his childhood, allowed himself a moment of reminiscence at the World Food Prize acceptance speech 2014. “My childhood wasn’t easy,” he

remarked. “My family made a meagre living growing maize, rice, wheat, sugarcane and millets. There were a few goats, cows and buffaloes as well.” Rajaram’s parents, he says, “valued education and made many sacrifices” to send him to school. “Seeing people live in poverty ignited a passion in me to dedicate my life to work that makes a real difference.” The newly-independent India in which Rajaram grew up was a tough place – at the time, 96 percent of rural children lacked basic schooling. “I was in the fortunate four percent,” Rajaram said. As acknowledgement of this, Rajaram dedicated a part of his $250,000 prize money to an educational institute in India.

Finding Norman Borlaug

Rajaram graduated with a BSc in agriculture from the University of Gorakhpur, which played a leading role at the time in the Green Revolution. He followed it up with an MSc in genetics and plant breeding from IARI and then moved to Australia, where he earned a PhD from the University of Sydney. A prolific researcher through his life, Rajaram had more than 400 research publications and had mentored hundreds of scientists around the world until his passing in 2021.

In 1969, after his PhD, Rajaram moved to Mexico to join CIMMYT, headed still by the legendary Norman Borlaugh, who would become one of the driving forces behind Rajaram’s own work. “It was a few years after the great events of the Green Revolution. Despite the food security gains, there was no time for complacency. There were mountains to climb and the fight against hunger has not yet been won. The fight for food and nutrition security had not even begun.”

Borlaug was quick to spot potential in the young man, who would spend his days wandering through small wheat farms, clad in baggy jeans and a sweatshirt, usually. Eventually, Rajaram went on to take over as the director of wheat research at CIMMYT and also as direct of ICARDA’s biodiversity and integrated gene management programme. He is also the owner and director of R&D for Resource Seed Mexicana, which promotes wheat varietes in Mexico, India, Egypt and Australia. “working for the poor and the hungry was the trademark of Rajaram. Borlaug was the main spirit of Rajaram’s work,”

said G. Venkataramani, Rajaram’s biographer and author of ‘

Mr Golden Grain, the Life and Work of the Maharaja of Wheat’.

Building worldwide food security

Rajaram was an active proponent of the private and public sectors working together – it is the only way, he believed, to tackle the enormity of the task at hand. “Feeding over nine billion people by 2050 will not be a trivial task. Sustainably increasing wheat production will have crucial impact on livelihoods and food security. For wheat alone, we will need to grow sixty percent more grain than now, on the same amount of land, while trying to use fewer nutrients, less water and labour,” Rajaram explained. “However, the staff of life for 1.2 billion people is one of the lowest-funded crops in terms of research.” It’s a daunting prospect, even after the robust successes of the Green Revolution.

Dr Rajaram is credited with developing 58 percent of all the wheat varieties that exist today, according to his biography. He is best known for his contributions to the development of two high-yield wheat cultivars – Kauz and Attila. These produce at least 15% higher yield than other types, holding more grains on each stalk. They are cultivated across over 40 million hectares worldwide. The process involved winter and spring wheat gene pools, shuttle breeding and mega environment testing.

Promoting young scientists

Working on the field and truly understanding the problems of farmers, Rajaram believed, was critical to promoting new ideas and technology. This is a nod to Borlaug’s legacy, which Rajaram dedicated himself to building. “Borlaug and I promoted the international community by connecting scientists across the world. Applied training should be the standard for any scientific institution,” said the

Global Indian. The way forward, he always said, was unity among the private and public sectors, free sharing of knowledge and seeds and training young scientists on the ground. “There can be no permanent progress in the battle for food and nutritional security until all the partners unite,” he remarked.

Dr Sanjaya Rajaram is also the winner of the Pravasi Bhartiya Samman, the highest civilian honour given by the Indian government to Indians abroad. He also received the Padma Shri in 2001 and the Padma Bhushan posthumously in 2022.

Published on 20, Jun 2023