(June 10, 2024) “I have tried to do good in the world via poetry,” Usha Akella, poet, reviewer, interviewer, editor, playwright, and creative nonfiction author, tells Global Indian. Having published nine books that include poetry, musical dramas, and creative nonfiction and founded Matwaala, the first South Asian Diaspora Poets Festival in the US, as well as the Poetry Caravan in New York and Austin that brings poetry to the doorstep of the disadvantaged, the 57-year-old has always worked towards reaching people with poetry.

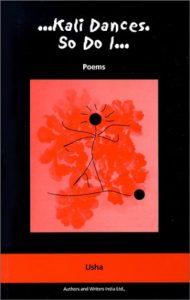

From her first book, Kali Dances, So Do I which came out in 1998, to her recent work, I Will Not Bear You Sons, she has always touched upon the topics of cultural traditions, feminism, immigration, travel, identity, patriarchy, politics, terrorism, and community. She has edited an anthology, Hum Aiseich Bolte, to celebrate Hyderabad, which was released at the Hyderabad Literary Festival in 2023. And she has edited a festschrift to honor poet Keki Daruwalla that was just published by the Sahitya Akademi.

Having immigrated to the US in 1993 after her marriage, she proved that knowledge is a lifelong quest when, at the age of fifty, she earned a Master’s from the University of Cambridge in 2018 in creative writing. Personifying the best qualities of being a Global Indian, she is deeply connected to her roots while she uses her work to create a difference across the world.

Usha Akella

Definitive formative years

Growing up in Hyderabad in the 1970s in a Telugu family, Usha calls them important years when summers were slow, filled with family, relatives, childhood friends, songs by MS Subbulakshmi and Ghanthasala, and an outing meant a trip to the bazaars of the city. Growing up with a father who worked in the then-RR Labs (now the Indian Institute of Chemical Technology) and a school-teacher mother, the campus was a green space and haven that was safe and centered around a close-knit community.

“Life on the RRL campus was a slice of heaven, innocent and uncomplicated,” she recalls and adds. “We are shaped by the times we come from, and those childhood values were instilled in us not by verbal teaching but by living a life centered around family and community. It was a certain India that existed at a certain time.”

The poet, till date, believes that India’s family structure is its greatest asset and that its philosophy of unity in diversity is inspiring. Her thorough grounding in Indian values and culture continues to motivate her and remains her safety net in trying times. It also inspires her constant striving to unite her writing craft with the community.

Unfurling her wings

After marriage resulted in a move to the US (from the Baltimore area to White Plains/Greenburgh in New York and currently to Austin, Texas), Usha drew strength from her Indian roots to assimilate and absorb the new way of life. She states, “The ability to adapt is a quintessential Indian trait. We have the strength to embrace new things and to work hard towards achieving our dreams.”

The only dream Usha always had was to write. Call it fate or genes (her grandfather’s brother, Uma Rajeshwarao, was a Russian and Telugu scholar, while her aunt Nidarmathy Nirmala Devi is a Telugu author, poet, and scholar), her childhood was characterized by three activities: read, write, and dream.

It was a dream that came true when she published her first book of poetry, Kali Dances. So do I in 1998, and I realized a life-long ambition. In those early days, prior to her first book, what helped her along the way were creative writing classes and doing poetry readings in Baltimore and New York to boost her confidence.

“For someone who wrote from the age of eight to finally be published was nothing short of miraculous. It was nothing short of a sadhana (dedication) that allowed me to fulfill a dream. When you pursue something without any expectation and work hard, it simply falls into place,” she states.

Charting new courses

Along with her poetry, Usha has worked tirelessly on initiatives that have a larger impact. The Poetry Caravan, which started in 2003, took poetry form from the confines of solitary readers and readings right into the heart of the community.

She explains, “While all of us are able-bodied and have the resources to engage in art (from movies to theater) or literature, what of those who have no access—be it prisons, hospitals, or senior homes? I thought of taking poetry to them via this initiative so that the disadvantaged are not cut off from the margins.” The initiative continued as a collective after she left White Plains for Austin and has offered over a thousand free readings when counted last. Though she is not directly involved with it any longer, it remains a lasting legacy she left behind.

Another brainchild of hers, Matwaala (co-directed with Pramila Venkateswaran), ensures that south Asian poets get the same opportunities as others and are not discriminated against. Working towards changing syllabuses so that there is diversity in curriculum and going to campuses to hold reading sessions where students are exposed to a fungible quality of voices, it works towards equality for poets of color.

She recalls with enthusiasm that during one of their sessions at NYU, Salman Rushdie walked in and stayed back graciously to listen to all the poets!

The power of words

Why does she write poetry? “It is my form of breathing,” she confesses. “Literally, I suppose. I was a chronic asthmatic as a child and youth while growing up in Hyderabad, which meant many days in bed by the window. I wrote to keep myself alive and feel alive. Perhaps the writer’s sensibility in me was formed in those days. I think that the primary reason is unaltered, though I am no longer in the grip of that ailment. I write to know I am alive.”

Art and literature are the glue that holds people together. For the poet, it gives ground for hope. She states, “At any given point in human history, there is always turbulence. It is the arts that unite. Write a poem, paint a canvas, and make a movie, and you are creating a virtual bridge for the world. We need to use art hopefully and carefully given the fractured times we live in.”

As emojis replace words and chats replace conversations, it is poetry that remains the last remaining bastion of emotion. It makes us think, ask questions, and capture consciousness. With her relentless quest to seek answers, Usha, through her work, is creating awareness and a witness to our shared histories.

Beyond poetry

When she is not reading literature of all genres, Usha likes to spend time with her husband Ravi and daughter Ananya, who, like her mother, is interested in the arts and is a trained Bharatanatyam dancer. She listens to numerous spiritual podcasts, paints occasionally, loves traveling, meeting friends, listening to music of all kinds, and visiting museums across the world.

As she signs off, I ask her, what has been the greatest gift poetry has given her? “Everything,” she answers, “Friendships, love, identity, travel, and my channel of evolution. I’ve learned to balance dreams with detachment, ambition with joy, and I see that I am the in-progress sum of all that I experience in my journey. Poetry reflects this centering self.”

- Follow Matwaala on their website.

Also Read: Alka Joshi: Re-imagining India as a debutant novelist at 61

Also Read: Gandhi & The Other Mohan: A childhood story takes author Amrita Shah to South Africa and beyond

The write-up covers different facets of the poet’s persona and talks about her creative journey at length. A very delightful are inspiring read. Congratulations and best wishes Usha Akella!