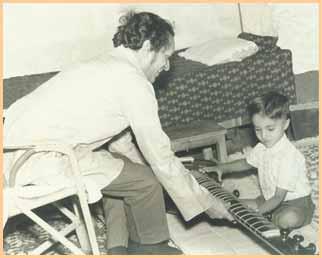

(October 2, 2022) Pandit Shubhendra Rao’s earliest memory is from when he was around three years old, of Pandit Ravishankar visiting his house in Bengaluru along with Alla Rakha and his own son, Shubhendra (Pandit Rao’s namesake) and showing him how to hold the sitar. By the age of three, Rao had already displayed a talent for the instrument, although he was too small to hold it upright. He would place it flat on the floor like his mother did the veena. The sepia-toned black-and-white photo of himself and his guruji is up on the wall behind him as he speaks to Global Indian from his home in Delhi.

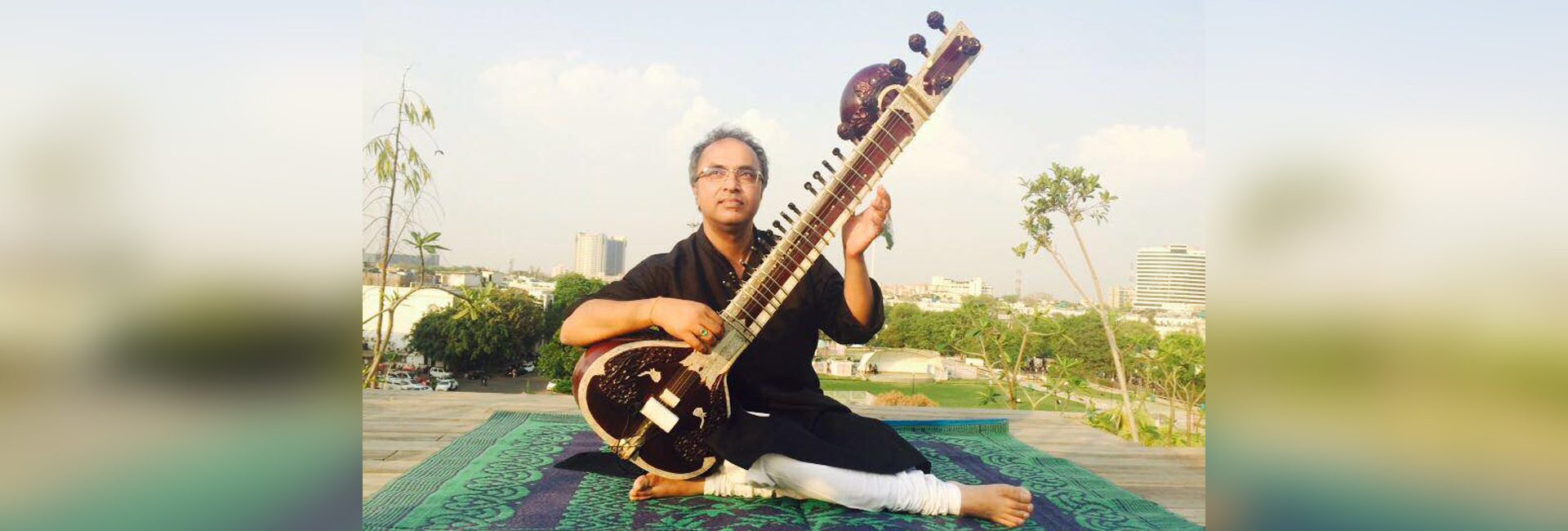

One of India’s top soloists, Pt Rao has collaborated with musicians from around the world and performed at the most prestigious venues and festivals, including the Kennedy Centre, Carnegie Hall, Broadway, the Sydney Opera House, the National Arts Festival, Theatre de la Ville, Beijing Performing Arts centre, National Arts festival in South Africa and the Dover Lane Music Conference. He’s also a long-time disciple of Pandit Ravi Shankar, has hung out with the Beatles and established himself as one of the foremost Indian sitar exponents of his time, a name known around the world.

Pandit Shubhendra Rao meeting Pandit Ravi Shankar for the first time. Photo: Facebook

Pandit Rao’s first teacher was his father, although Pandit Ravi Shankar would check on his progress every time he was in Bengaluru. “I was seven or eight when I got my first lesson from him.” “He had a concert in Mysore and I had taken my sitar with me. That morning, he sat with me for half an hour.” From then, he would receive a class every time the maestro was in town and when he was old enough, would meet him if he was in the country. The child performer gave first concert on AIR Yuva Vani when he was a teenager.

Following his bliss

“You will get a bachelor’s degree, but what will that piece of paper do for you?” They were seated on the huge lawns of Pandit Ravi Shankar’s home in Delhi, where a young Shubhendra had just moved to live with his guru. Pandit Rao was taken aback – back home, all his friends were focussed on the only two ‘kosher’ choices, engineering and medicine. Pt Ravi Shankar pressed on: “You seem to have chosen music, why not take that further? Instead of spending eight hours in college, dedicate that time to your practice instead. Beta, I’m a fifth standard fail. Do you consider me any less educated than a person with a PhD?”

That settled the matter. “He was telling me, if you know what you want, go with it, become a master. That’s the real education.” Perhaps that’s the answer Pandit Rao was hoping to hear. “But that’s the job of the guru, isn’t it?”

After that, Pandit Rao remained in Delhi. All they had to do was practice, the ‘true Guru-Shishya Parampara,” he calls it. In turn, he did his own service too, taking care of his guru’s personal and professional requirements, even becoming the signatory to his bank. “I was learning about life in a way I couldn’t have imagined. I was taking appointments with ministers (Pandit Ravi Shankar was a Rajya Sabha member) and setting up meetings and keeping up with my own practice.” And there was the glamour of being by the maestro’s side – “He taught the Beatles how to play sitar and was one of the icons of the hippie movement in America,” Pandit Rao says. In 1973, George Harrison, who wanted a South Indian meal, visited his home in Jayangar, Bengaluru.

Signs of genius might have shown up early, but life as Pandit Ravi Shankar’s disciple allowed no compromise on discipline and hard work. “We would wake up at 4.30 am and begin the day with four hours of practice,” he says. “I did this for about eight years.”

Spic Macay, Hong Kong

The first performance

In 1985, when he returned home after running errands, he was told, “Guruji has been calling you for 45 minutes.” The dedicated student ran at once to meet his guru, who said, “Jao, sitar tune karo apna. Umashankar is not coming, you can sit with me today.” Pandit Rao emerged from the room open-mouthed, to find tabla maestro Swapan Choudhary, who was to play with Pandit Ravi Shankar that day, smiling at him. “Don’t worry,” he said. “All his disciples will part with a hand to sit with him on stage. If he didn’t think you were ready, he wouldn’t have asked you. Trust yourself and trust your guru.”

In August 1987, he gave his first performance alone as a protege of Pandit Ravi Shankar, at the Guru Nanak Bhavan in Bengaluru.

On the world stage

In 1988, at the Kremlin, Rajiv Gandhi and Mikhael Gorbachev sat in the audience. Pandit Rao was among twenty eminent Indian musicians joining the Russian Philharmonic, the Russian Choir and the Russian Folk orchestra. Pandit Ravi Shankar was conducting – this was the grand finale of the year-long India-Festival in Moscow. “This was my first time outside India,” he smiles.

In the 1990s, he got his first big break, during a trip to the US. “There was a big promoter in America at the time, promoting musicians like Pandit Hariprasad Chaurasia and Pt Shiv Kumar Sharma. I was one of the younger musicians in the lineup.” In 1997, he did his first solo performance in Paris, at the Theatre de Leville, at a show that was 90 percent sold out. The next morning, as he walked through the streets, someone stopped him, asking, “Hey, didn’t you perform last night?”

Carnegie Hall and the International Music festival in Salzburg

Pandit Rao had begun finding his feet as a global performer, pushing the boundaries of the Hindustani tradition and collaborating with musicians from around the world. One of the first was with Pipa maestro Gao Hong – “The instruments are very similar, so we composed for each other.” They performed together at Carnegie Hall, New York.

“I have also played at the Royal Festival Hall, Queen Elizabeth Hall, the International Music festival in Salzburg…” Pandit Rao frowns as he recalls, his is a long list. In Salzburg, the birthplace of Mozart, his concert was scheduled for 6.30 am on a Sunday, in a church. He wasn’t expecting anybody to show up. “All 800 seats were sold out three weeks before the show. That’s the amount of respect they have for culture in that part of the world. In India, it’s hard to get 80 people, even in Delhi where no concert is ticketed.”

Foreign embassies got in touch with Pandit Rao if there was an artist visiting. He was becoming a known name in music circles around the world. In 2005, the American Embassy asked him to collaborate with the guitarist Freddie Brent, with whom he remained in touch. The duo performed together later, in Amherst and New York.

Halloween night at the Sydney Opera House

On October 31, 2008, Pandit Rao was scheduled to perform at the Sydney Opera House. “I was prepared, I had changed the strings on my sitar, everything was in place.”

Five minutes into the concert, his main string snapped. “There was nothing I could do. I had to put the sitar down and re-string it.” That took a good three minutes, even for an expert like himself. He closed his eyes and resumed playing. That evening, his tabla player’s instrument cracked and he had to change it too. Ten minutes later, the sitar string snapped again. Pandit Rao lightened the mood with a joke – “It’s Halloween and I think there are a lot of spirits around. That’s why we call our music spiritual.”

One learns to handle these situations with time, he explains. “At that moment, you have no choice but to take a deep breath and relax.”

Home, in Delhi

In 1993, he met the woman he would marry. Saskia de-Haas was a Dutch cellist in Delhi to further her knowledge of Indian music by studying under the great masters of the time. They remained friends for five years and caught up occasionally in Amsterdam. “We realised we had a life together and it’s been a wonderful journey,” he smiles. Saskia Rao-de-Haas is a musician and scholar in her own right – her latest book, Shastra, is a magnum opus that traces the origin of Indian classical music from 5000-6000 BC to the present day. She has also modified the cello for Indian music.

The couple perform together and live in Delhi with their son, Ishaan, a pianist now at the Berklee College of Music. They also run the Shubhendra & Saskia Rao Foundation, an NGO that introduces a new approach to music education in India, which they call, A ‘Glocalized music experience’. Their life together is truly multicultural, with four languages spoken between the three of them – Dutch, English, Hindi and Kannada. “Even our cuisine is global, from bisibelebath to goulash,” he smiles.

Pandit Shubhendra Rao says India will always be home, even if he has learned a great deal from his time abroad. However, like his guru, Pandit Ravi Shankar, he has never shied away from pushing the boundaries of Hindustani Classical music, making huge strides towards increasing India’s soft power around the world.

Follow Pandit Shubhendra Rao on Facebook

Also Read: The rhythm divine: Ustad Zakir Hussain, the tabla virtuoso whose music bridged continents

Also Read: Raising the bar: The remarkable journey of record-breaking pianist TS Satish Kumar

🙏🙏🙏🙏🌸🎼🌻🌷👩🎨