(August 2, 2022) In the dense forests of the Western Ghats, somewhere in the Nilgiris in Tamil Nadu, the birds and insects make quite a racket, chirping incessantly through the still morning air. Rising through the din are the strains of a flute. The source of the music is Dhruv Athreye, the protagonist of the docu-fiction film, The Road to Kuthriyar, who sits beside a crudely fashioned Shivling. Here, nature is akin to God, stones and trees are often marked out, adorned with sandalwood paste and flowers by the locals who come by to offer their prayers.

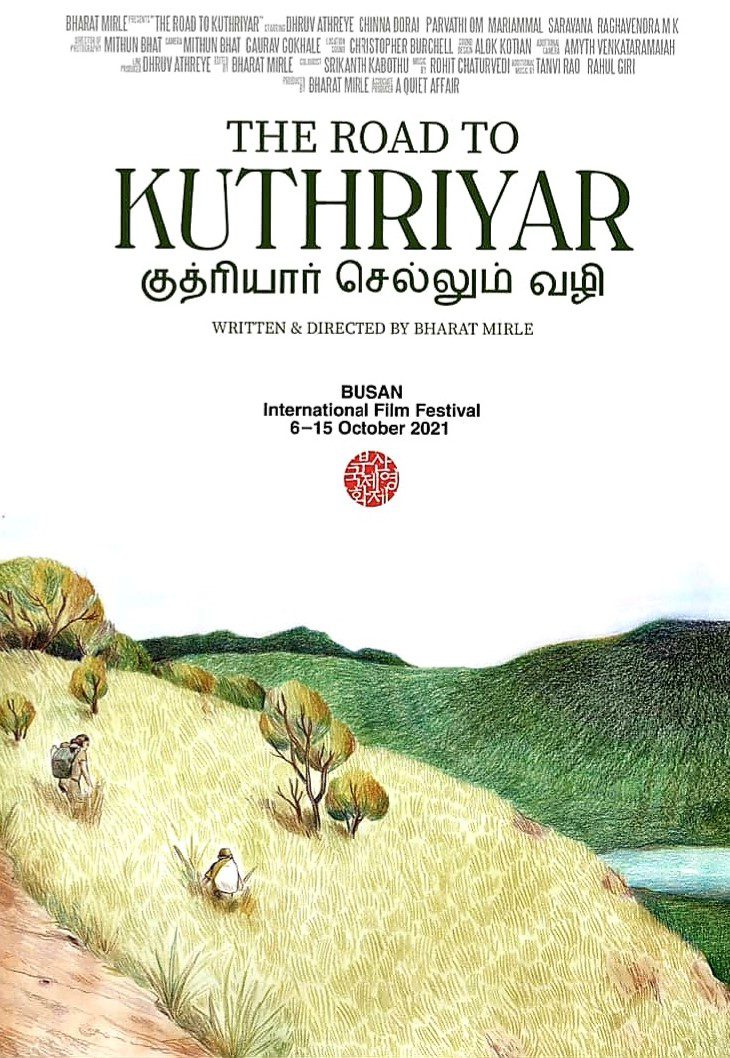

Bharat Mirle’s debut foray into feature-length films, The Road to Kuthriyar is an ode to the magnificent eco-zone that is the Western Ghats. In a couple of weeks, the film will be screened at the Indian Film Festival of Melbourne, along with Surya-starrer Jai Bhim and a curated lineup of other Tamil films. It also premiered at the 2021 Busan Film Festival in South Korea, one of the most significant festivals in Asia. The film draws the viewer into the heart of the Western Ghats, through the story of an unlikely friendship between Dhruv, an amicable researcher from Bengaluru who is conducting a mammal survey across the 600-kilometre Kodaikanal Wildlife Sanctuary, and Dorai, a local tribesman with a drinking problem, whom Dhruv recruits to serve as his guide.

As Dhruv plays his melancholic tune, a figure emerges from the foliage, pulling away on a beedi clutched in his right hand. “Hello. Don’t play over there. Nagamma will come,” he calls, picking his way through the grass. When Dhruv pauses, perplexed, the man launches into a little dance to demonstrate his point, fashioning his hands overhead to mimic a cobra’s hood. “Nagamma,” he says again. “Big snake will come.” He introduces himself as “Meen (fish) Kumar” and sits down beside Dhruv to talk on the phone, saying, in Tamil, “I’m in a shoot now.” This is where the story begins and as it unfolds, Dhruv finds that navigating his intrepid guide is as tricky as the dangers the forest holds.

It’s a jungle out there

The film brings to the fore the perils of rampant urbanisation, infrastructure projects, mining, and tourism in what is one of eight UNESCO World Heritage Centres around the globe. Believed to be even older than the Himalayas, the great Indian gaur, the world’s largest bovine, is an everyday sight, as are elephants. Locals are always happy to describe a hairy encounter with a wild boar or tell you about that time a leopard came prowling. The more dedicated trekkers, who befriend the tribal communities who live in the mountains and venture even deeper into the forests, will tell you about the tigers and lions too.

The rustic feel of a hand-held camera and seemingly unscripted dialogue were all part of Bharat’s plan. “The idea was initially to do a documentary,” Bharat tells Global Indian. “I had heard of someone doing interesting work in the Western Ghats and realised that the person was, Dhruv, whom I knew.” This was back in 2018 and Mithun Bhat, the film’s cinematographer, had already met up with Dhruv and taken the necessary permission to shoot. “After I met them, however, I thought it was more suited to the docu-fiction space. I wanted to tell a story.”

That’s how Bharat Mirle arrived at the Kuthriyar Dam. By this time, Dhruv had already spent about two years in the region, conducting his survey and taking on sundry social projects like building eco-friendly toilets. “As we did our research, we realised that there was so much about Kuthriyar that we didn’t know, that even Dhruv didn’t know,” Bharat explains. A dam, or any other form of large-scale government infrastructure, gives rise to pockets of civilisation, small communities who move nearby to eke out a living. “We tend to romanticise these things,” says Bharat, who is based in Bengaluru, where he is a full-time filmmaker. “We think of this beautiful, simple life but that’s not the case at all. But the idea is to tell a story without passing judgment. We saw things that made us uncomfortable, like alcoholism, for instance, but our duty was to tell the story without compromising its integrity or passing judgment. It is always a point of view and in this case, we tell the story through Dhruv’s eyes.”

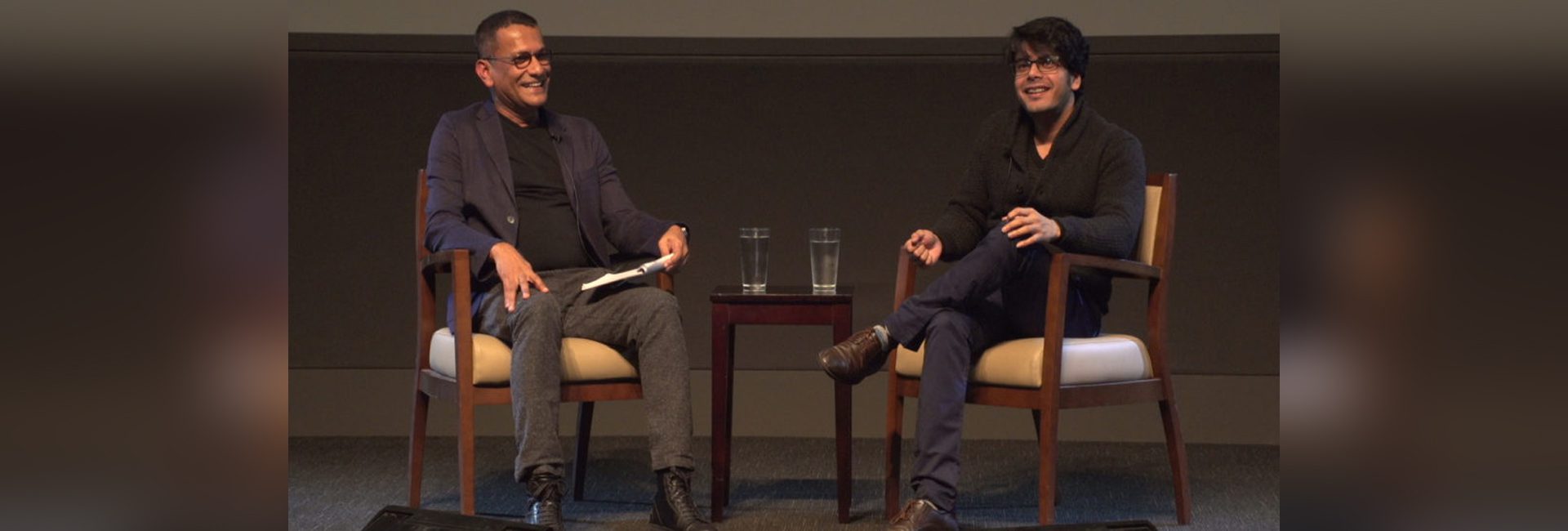

Bharat Mirle

A story within a story

Bharath decided to fund the film himself – although he has a fairly substantial repertoire as a writer, director, and editor, this was his first attempt at a full-length feature film. Working on a small budget with little freedom to experiment, they adopted what Bharat calls a “guerrilla style,” with “no setup, we would just go.” There was a sound guy, a cinematographer, Dhruv and Bharat, and later, a camera person. “You just go, set up, and start shooting. If we needed an actor, we would say, “Hey, do you want to be in the film.” The script too had been written around people we had met. “There were scenes when Dhruv or Dorai are actually talking on the phone for real.”

Much of the film plays out according to a prepared script but these little vignettes bring in the feel of a documentary. He wanted both – the finish of a scripted, well-planned feature film and the rustic spontaneity of a documentary. “It struck me when we were doing the initial film. So, The Road to Kuthriyar became a film in which the protagonist is making a documentary.” He attempts to understand India, to gain insight into the lives of the less privileged, rural communities, who carry out their lives in a complex exchange with the government.”

Kodaikanal to South Korea

Shooting began in Feb 2019 and was complete just before the pandemic hit, as Bharat’s team had begun to plan the release. “It was nerve-wracking,” he says. “You have spent two years doing this and now, the world is in lockdown and you don’t know what’s going to happen.” His worries proved unfounded, however, when The Road to Kuthriyar was part of ‘A Window on Asian cinema” at the Busan International Film Festival.

The exploration of our fragile, imperiled forest ecosystems, is a theme he has dealt with several times before. His advent into films and storytelling was also something of a given, he recalls that storytelling was always a childhood love. “Initially, I wanted to be a writer,” he says. “I was raised around literature and films.” His parents were both writers and his grandmother taught literature, so stories were always a part of his life.

A still from the film with Dhruv Athreye (left)

The filmmaker’s journey

Back then, in the early 90s, access to equipment was very limited, although Bharat recalls friends whose parents had ‘camcorders’. “We would hang out, make home movies and act in them as well,” he smiles. That marked his first foray into filmmaking, although making films for a living was decidedly not an option at the time. “I was in college when the DSLR revolution happened and I decided I wanted to be in films.” His parents, both writers, had cautioned him, telling him not to be a writer at any cost. “Being a writer is also a lonely job. Filmmaking is by nature collaborative. It also gives me the chance to meet more people.”

After a brief stint with a news channel, he quickly realised it wasn’t the life for him. Bharat then decided to try his hand at advertising and “was okay at the job,” he says. From there, he took the leap, joining Nirvana Films, an established film house at the time, as a trainee, which was one of the early filmmakers entering the documentary space. “There, I learned how to do less with more,” Bharat says. With two friends, he co-founded Yogensha Productions, to make corporate films as a way to make some money. Their film, 175 Grams, which told the story of FlyW!ld, the Chennai-based Ultimate Frisbee team, went on to win the Short Film Award at the 2015 Sundance Film Festival.

In Stories of Resilience: Chikkaballapur, produced by Bharat Mirle and Quicksand, they meet Narasimha Reddy, a small-scale farmer in Tumkur, an expert in traditional, organic farming practices and the use of indigenous seeds. In Byramangala, part of the same series, a group of cattle herders risk a polluted lake so they can feed their cows.

In 2017, Bharat was the director, writer, and editor of Vaahana, which was selected for the 2018 Jakarta International Humanitarian & Culture Award, the 2018 New Jersey Indian and International Film Festival, and the Bangalore International Short Film Festival. Bharat was also an editor on Krithi Karanth’s Flying Elephants: A Mother’s Hope, where a mother elephant confesses her fears to her little calf. The film was named the Best Global Voices Film at the Jackson Wild Media Awards and was selected for Wildscreen, Environmental Film Festival, S.O.F.A. Film Festival, and the Ireland Wildlife Film Festival.

- Follow Bharat Mirle on Instagram