(October 15, 2022) Waswo X. Waswo arrives at our video call looking irritable. The electricity had been erratic through the day – in Udaipur, the absence of air-conditioning is a serious problem. He has just returned from San Francisco, where he gave a talk at the Asian Art Museum. “I was afraid they would ask me to state my pronouns,” he tells Global Indian, only half-jokingly. Waswo is the “old fashioned liberal,” not given to accepting unfairness or dogmatism without a fight. It’s a personal struggle, one that has also defined him as an artist.

As we speak, he was preparing for another debate, this time in Delhi, put together by Aakshat Sinha, on ‘wokeism’ in art. “Of course, I’m the anti-woke contingent.” His art, an intermingling of photography and miniature painting styles, is a visual treat – it reminds me always of Henri Rousseau but mirrors his journey to find his identity, as a human being and as an artist. He works in the ‘karkhana’ style, working through collaborations with local miniaturists and border painters in Udaipur, reviving their legacy, bringing the artisans who have gone without credit for generations, to the fore, in India and abroad.

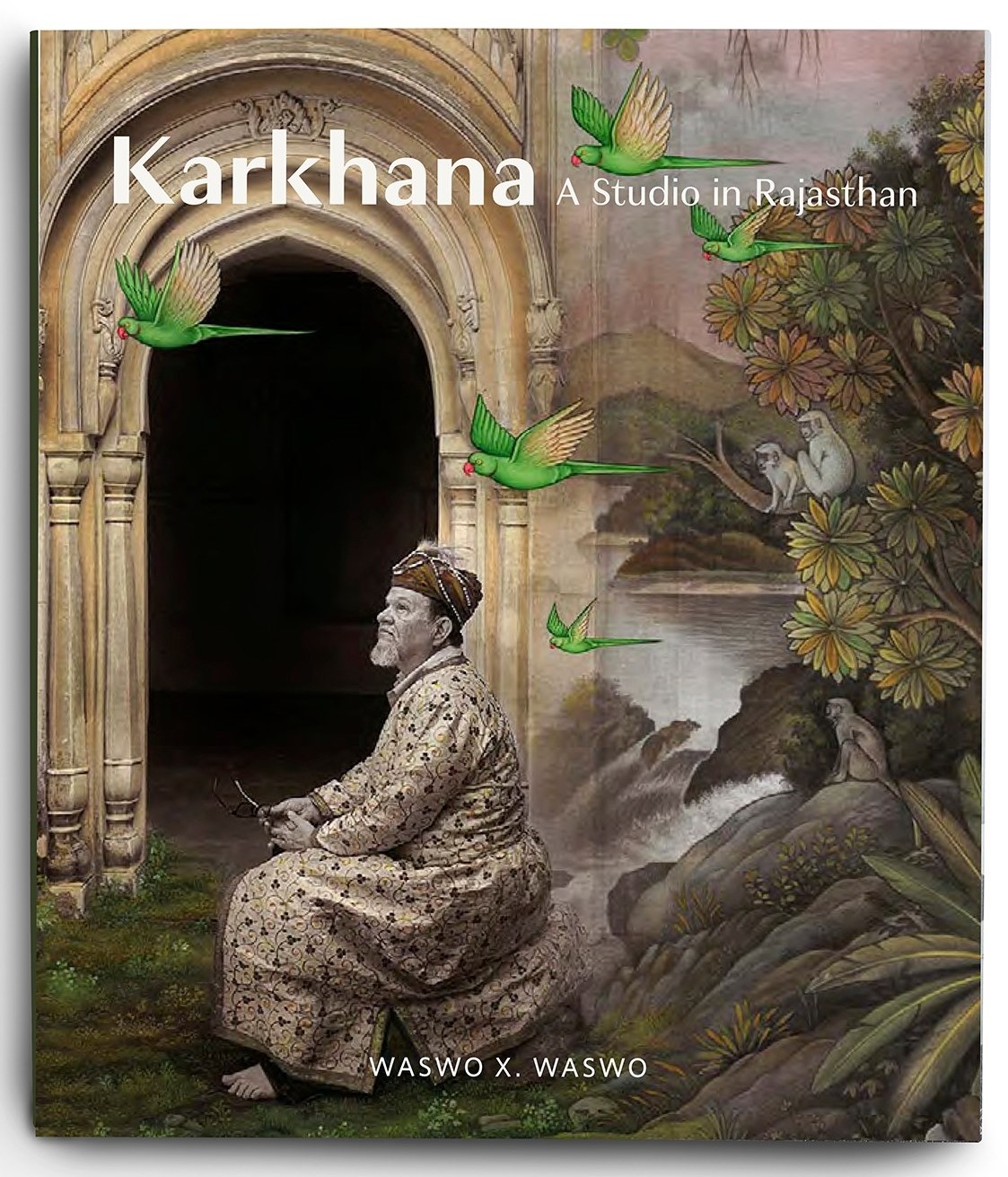

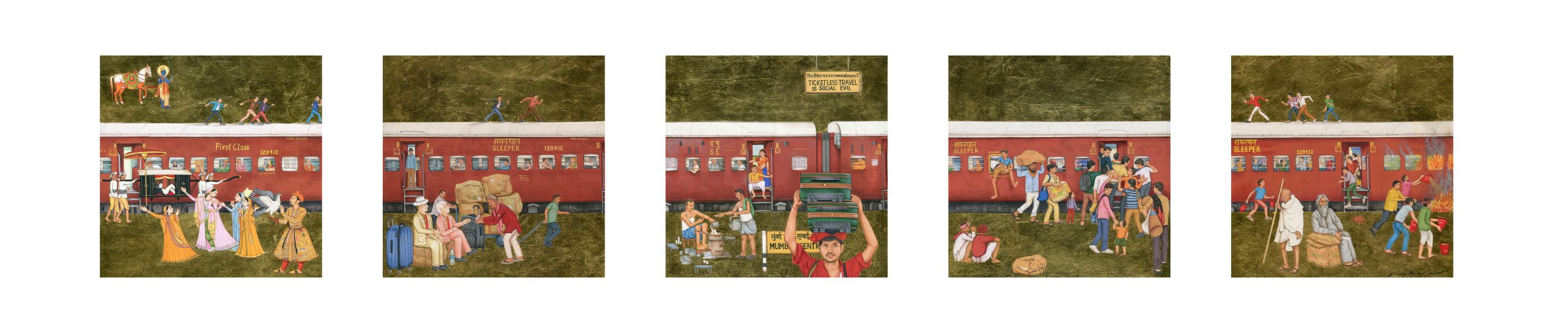

In his latest book, Karkhana, which will be out in November, Waswo documents his decades-long association with Indian artists – he works out of Udaipur, which has been home for the last two decades. His work comprises two styles, which often mingle with each other. There are hand-coloured digital portraits he co-creates with Rajesh Soni and the contemporary miniatures, which he conceptualises and are painted by the miniaturist R. Vijay, who also comes with a rich artistic lineage. Their collaboration of over fifteen years is a blend of genres, where Waswo himself is the protagonist, the bumbling foreigner trying to make sense of India. This extends to the miniatures, done in the Mughal, Mewar court Company School styles.

Udaipur – and the karkhana approach

Wandering through the bazaars of Udaipur, in his early days in India, Waswo fell in love with the miniatures on display in the shops. “They were generally low quality but I liked them.” They were done following the karkhana style, with groups of people working on a single painting. The shopkeeper, however, announced proudly that he was the artist. Waswo learned soon enough about the artists who work quietly in the background, as they have for generations, never signing their work. When he began collaborating with R. Vijay, who comes from a long line of artists himself, Waswo had to coax him to put his name on it. “He said his name didn’t belong on it and I had to push him to sign. Now, he always wants to sign his paintings.”

Waswo X Waswo first came to India in 1993 and spent 10 days here. In 1999, he came back and spent a month in Rajasthan. “That was when I started to fall in love with the place,” he smiles. In the fall of 2000, he returned with his partner, Tommy, and stayed on for six months. “In 2006, I bought the home in Udaipur because I wanted to work with the craftsmen there. I see one of my jobs as finding what people are good at and trying to incorporate that into my work.”

The etymology of the karkhana, Waswo explains, goes back to ancient Persia. It’s a story reminiscent of Orhan Pamuk. Karkhanas were artisans’ workshops, which were brought to Delhi through the Mughal courts of Jehangir and Akbar, and miniatures were painted. “When Aurangzeb came to power, the artists were terrorised and escaped to places like Rajasthan, where they found patronage under the Maharanas of Bikaner and Jaipur,” he says. It led to the founding of the Bikaneri, Alwar, and Mewar schools of art. The system continues to live on – “I didn’t meet R. Vijay directly,” Waswo says. “I met him through a shopkeeper.”

When he first started creating work in Rajasthan, Waswo was a photographer with a Rolleiflex and a dark room he had built for himself in Udaipur. “In the US, I used Ilford chemicals and paper and knew how things were mixed, as well as how to control water temperature. Here, the darkroom was always hot and dusty – dust is a real problem with negatives. I couldn’t find the right chemicals either.” The time had come to go digital and Waswo bought himself an Epson 2700, the first high-end digital printer in Rajasthan. “I met Rajesh Soni around this time, he saw the black and white photos I was printing up and said he could paint them.” His grandfather, Prabhulal Verma, was a photographer for Maharaja Bhopar Singh of Mewar. “I pushed Rajesh to colour the photographs and one thing led to another.” It resulted in a collaboration that lasted over 15 years.

The Campbellian struggle

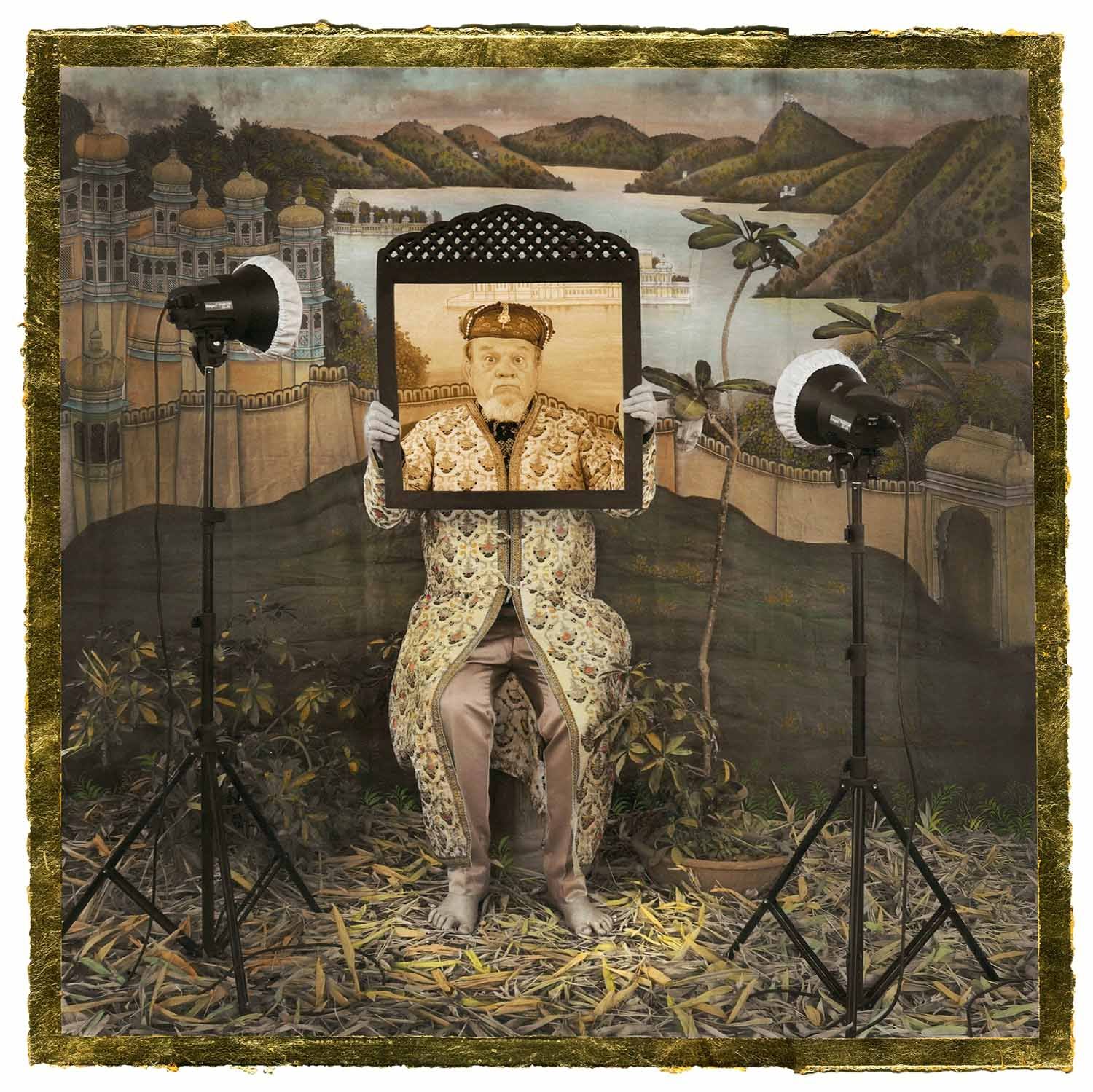

“Through my paintings, I have learned to look at myself and question myself,” Waswo tells me. “When I started, I was taking photos and writing poems, always with the idea that I would go back to the US and exhibit them. India was my subject and not my audience.” He attracted quite a bit of criticism from the west, however, for his supposedly “white gaze.” He was told he was “editing out modern India and keeping people blind to the truth.”

The western gaze, it seemed, wanted to see the crippling poverty, the starving children, and the dirty streets, not the moments of poignant beauty in which Waswo found inspiration. “I have always taken photos based on pictorialism, I like beautiful landscapes and common people – I like them as people. They have a lot of self-worth and awareness of that self-worth too.” Coming from the US, where so many children are born to single parents, he found a deep appreciation of the Indian family structure.” His critics, however, decided he was demeaning India.

Struggles against postmodernism and the ‘evil orientalist’

He has always been a rebel, however, never given to conforming, either to the left or the right. In the US, in Wisconsin where he grew up in a Christian home, he came to terms with being gay. “I was very much on the left then, fighting for gay rights. I even made a speech to the Senate.” In India, the struggle against the western system continued, albeit on the opposite side this time. “It has been a battle,” Waswo admits. “I have been battling post-modernism for a long time, much before Jordan Peterson started talking about it.”

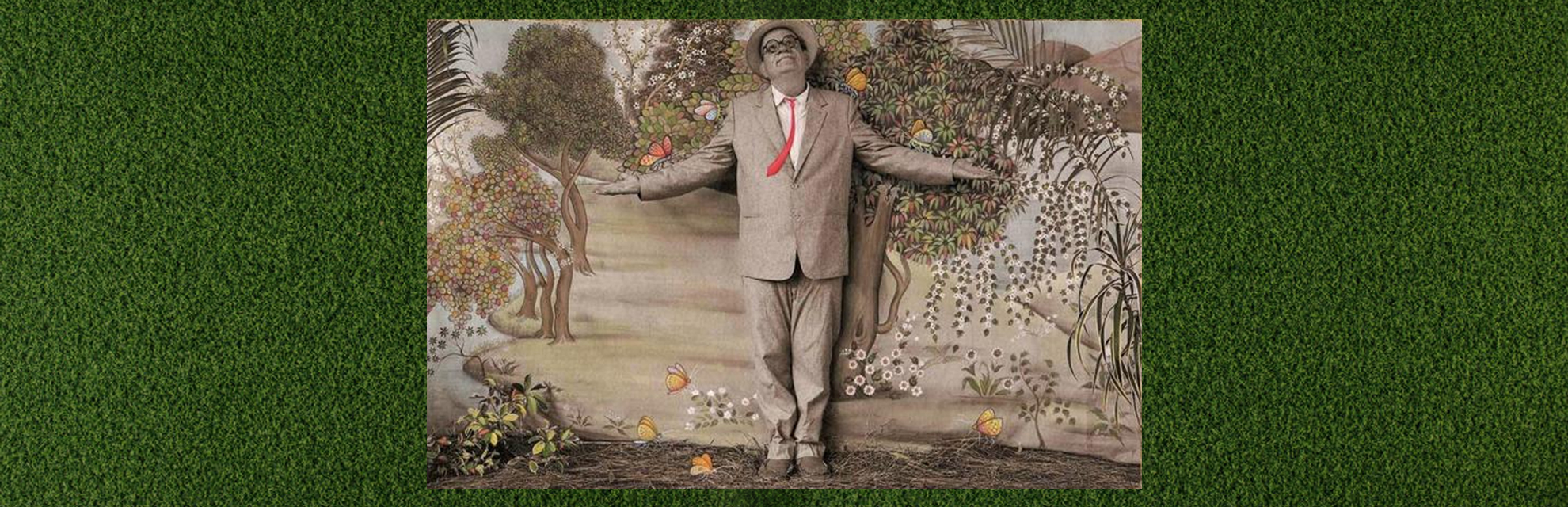

As he struggled to find himself and stay true to the artist within, Waswo found a solution – introducing himself into his works. Several series of miniatures were born of this – The Secret Life of Waswo X Waswo, Early Work with R. Vijay, A Dream in Bundi, and Lost. “I introduced myself into my work,” he says. “He’s the bumbling foreigner in India. The outsider doesn’t understand where he is but still has an appreciation for the wonder, beauty, and kindness of people. He has grown into his own man now.”

Sometimes, he’s the “evil Orientalist,” a role he plays gleefully and to the hilt. In other words, he’s wearing a fedora and a suit, chasing butterflies or squinting disapprovingly through his spectacles at a scene that is poetically, spectacularly Indian. In the series, The Observationist at Leisure in a Stolen Garden, he’s also chased by a crocodile. Waswo and I go back many years and although I have seen his work for a long time, at first glance, I confuse him with the French master, Henri Rousseau. Waswo looks pleased when I tell him this. “He’s one of my favourite painters. He’s an outsider, who taught himself how to paint. He never even went to the Tropics, although he paints them extensively. I’m the same. I have no degree in fine art, I’m a photographer.” The artists he works with are “very naive,” far removed from the elitism of the art circles. “The artists were trained by other miniaturists but don’t have academic backgrounds like many others in the art scene.”

The India Art Fair

Waswo is now also working on a solo booth at the India Art Fair. He shows me around the works as we speak and sends me a photo of artists working on gold leaf linings. This series is a shift from Waswo’s usual work. His artist, Chirag Kumawat, specialises in both realism and miniatures. “We’re combining hard-core realism with miniature elements, it will be something nobody has seen before.” Even Kalki, the god of destruction, makes an appearance in the paintings. “The world is changing at a very rapid pace. With the advent of AI, shifting politics, climate change, and pandemics, we are at a crossroads. Kalki makes an appearance because this is a time of chaos and we have to wait and see what emerges in the new era.”

Follow Waswo on Instagram and Facebook

Enjoy his work and enjoyed his introduction as well.