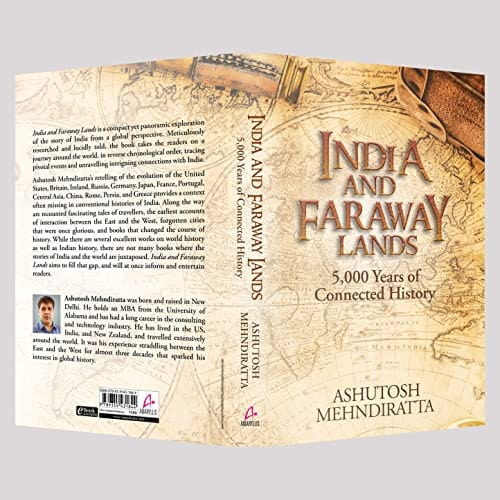

(June 18, 2024) A decades-long quest to understand his own identity culminated, for Ashutosh Mehndiratta, in his debut book, India and Faraway Lands: 5,000 Years of Connected History. The magnum opus has been condensed into a 386-page, imminently readable history of India and the world. It was a journey that began when he first moved to the US in 1995 as a student, where he remained for the next decade or so.

“When you’re living in India, you don’t think of yourself as Indian. When you step out of the country, you become very aware of your identity – you’re Chinese, Sri Lankan, or Indian. It’s a very simple but unique distinction Indians living in the country may not appreciate,” Ashutosh tells Global Indian, as he connects with me from his home in Eastern Canada.

Finding inspiration

Growing up, Ashutosh Mehndiratta would listen to his father tell stories of the Partition – both his parents were born before in pre-Independence India, in what is now Pakistan. When the partition took place, his parents’ families were among the millions who braved the bloodshed to travel to India, huddled in crowded trains, praying for their lives. “My mother was too young to remember but my father would tell me stories,” he says.

“We grew up reading Amar Chitra Katha and hearing stories about how India was IT – the golden bird. But today, we can see that other countries are far more developed and wealthier in many ways. If India had such a glorious past, when did it change,” asks Ashutosh, as he joins me for a chat from his home in Canada, where he now lives with his wife. How did this change happen – was it gradual or sudden?

Ashutosh Mehndiratta

The identity question

When he left India, he became aware of his identity as an Indian, which left him with many questions. How did India rise to greatness and what led to its fall? Some experts suggest geography, others say religion – Ashutosh, who naively believed he could read a few books and find an answer, realised, through years of research, that there was no one clear reason. Countless influences act upon a country, from within and without, to determine its transition to wealth or poverty.

“Over the years, I gathered so many notes and books that I thought, ‘Why don’t I write a book of my own?’ I started about six or seven years ago.” He was living in New Zealand at the time and in this case, geography really was the answer. “Living outside India was a good thing – there were fewer distractions. I lived close enough to the office to walk home as well, so I had time on my hands.”

Catching a break

Ashutosh Mehndiratta came back to India in 2017, where he headed Cisco’s Bengaluru’s account. In 2018, he attended the Bangalore Literature Festival, where the Lit Mart, a platform for aspiring authors to make pitches to major publishing houses, is a big draw. It can mean a big break for first-timers – “There is a 99.9 percent chance you won’t hear back from a publisher unless you are an established academic or Bollywood star. A history enthusiast without a pedigree rarely stands a chance,” Ashutosh admits.

Lit Mart did in fact open those doors for the techie-turned-historian, who met a representative from Manjul Publishing House. “I wrote to Rashmi and her editorial team liked the idea, so we began the editing process. That is a long journey – as a first-time author you don’t know the scale of effort that goes into editing.”

India: A History

The book gets off to a surprising start – it begins in the present and moves backwards. “History books begin in the past and move to the present but I personally feel it is not logical. The present is more familiar and relatable. I grew up in the ’80s and ’90s, I saw history being made when India won the World Cup. That resonates more than the Indus Valley Civilisation.” He wanted the subject to fascinate his reader as much as it did him, so he decided to go backwards, starting out with the 1930s, Independence and Partition.

“We have all grown up hearing that Gandhi’s peaceful protests got us independence,” Ashutosh remarks. “But the British empire itself had vanished – the country had gone bankrupt and London was destroyed. They had no will or resources to maintain a colony. In 1946, as Britain was left devastated by World War 2, came the Royal Indian Naval Mutiny. It was a failed insurrection but scared the British, nonetheless. For the first time, they realised the might of Indians bearing arms against them. The US had also come out of the Roaring Twenties and domination meant having to dismantle what was left of the Empire. The Japanese had also weakened the colonialists, forcing them to surrender in Singapore. Subhash Chandra Bose had also been running his propaganda war through a radio show he did from Germany.

Imagine there’s no country

During his study of Indian historians, Ashutosh found they were all confined to the boundaries of India. “Their story begins in 1608, when the first ship landed in Gujarat. They don’t ask why someone in a small island nation would get on a boat, go around Africa and travel 18,000 km to reach India. What was their motivation?” He discovered that a year earlier, in 1607, they had landed in Jamestown in America. “So, I thought, let’s take a break from India and see what was happening in London at the time.” He learned that London was a small city trying to enter the merchant trading business, attempting to compete with the Portuguese who had become rich through trade, bringing in silk from China and spices from India. He couldn’t just study India in isolation, everything is linked to everything else.

What’s more, when the British first arrived to trade with India, they were welcomed. “That was boom time,” Ashutosh says. “Like Bangalore is now – big tech is pumping money into the city. Of course, it would be a different story if big tech took control of the government but until then, we all love the millions we receive!”

A story of interconnectedness

“I wanted to focus on the interconnectedness of history,” Ashutosh says, adding that the cost was sacrificing depth to cover 5000 years in less than 300 pages. Instead, all his years of reading go into a voluminous bibliography. “The idea is to invoke curiosity in the reader,” he says.

The stories are remarkable – Ashutosh Mehndiratta tells a couple to appeal to the Bangalorean in me. For instance, “My job was Bangalored” is a common dotcom era joke in the US but there was another period of close ties between Bengaluru and America, back in the late 1700s, when Haider Ali, of all people, was a household name on the other side of the world. “The Americans were fighting the British, as were Ali and the French. The Anglo-Mysore wars made it to American newspapers and Haider Ali became “Haider Ally”. They would talk about his son, Tipu, the prince using rockets in war.”

When America won its freedom in 1783, it was a young country with lots of land and no money. “They sent their first ship to India,” Ashutosh says. “The ship arrived in Pondicherry, had a flag and was called the ‘United States’. That’s how they began their trade and eventually grew into a superpower.”

Drivers of progress

Could he identify trends that result in progress more than any other? “Any country that allows freedom of expression has progressed,” he says. “If you can express, debate and critique freely, it brings out the best in people. Trade is also important and because of that, places near calm oceans or rivers tend to thrive.”

Ashutosh Mehndiratta hopes his book, with all its fascinating anecdotes, will inspire his audience to read more, to learn about their Indian identity. “It’s not something that Indians at home are aware of but it comes up when you’re abroad,” he says. Since his wife works for an immigrations company, even their dinner table talk is diverse and multicultural. “Meeting people from other cultures, compels you to learn about the world and yourself. Diversity really brings out the best in you.”

Follow Ashutosh on LinkedIn.