(June 1, 2024) When the pandemic hit in 2020, people began washing their hands often, wore masks when they stepped out and maintained social distancing protocols. When the vaccines were rolled out, they lined up to receive them. Ramit Debnath, a Gates-Cambridge and Cambridge Zero (the university’s climate action initiative) scholar, wondered how the government went about tackling a task on such a massive scale and how over a billion people, even those who were not personally affected, conformed to a new and elaborate set of rules. The winner of the Turing Enrichment Award, Ramit, who is currently at Churchill College, Cambridge University, found that some methods used were in line with the Nudge Theory, a means of using positive reinforcement to modify behaviour.

At no point did the Indian government, for one, declare vaccines mandatory. While lockdowns and other measures were put into place, punitive and coercive techniques but the latter can only be applied with very strict limitations and protocol like washing one’s hands regularly cannot be constantly monitored. After all, this is not the world that Anthony Burgess’ famous anti-hero, Alex, inhabits in A Clockwork Orange, where negative reinforcement can be used to alter behaviour. However, those who paid close attention might have noticed what experts call ‘behavioural nudges’ – from things as seemingly bizarre as banging cutlery shouting “Go Corona Go’ or the ‘clap for carers’ initiative, or the countless pictures of politicians proudly flaunting their masks. The idea is simply based on positive reinforcement, if you see your family, friends, neighbours, and your favourite public figures wearing masks, you’re more likely to do so yourself.

Bridging data science, AI and policy

Ramit, who now works on countering climate misinformation using Machine Learning to analyse crowd intelligence on Twitter, used Artificial Intelligence and ‘topic modelling’, looking to see how often terms like ‘health’ occurred across social media posts and government communications. He found that behavioural nudges did in fact occur across communication channels. The Nudge Theory is fairly new, developed as recently as 2008 by behavioural economists Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein, in their book, ‘Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth and Happiness’. “Choosers are human, so designers should make life as easy as possible,” they write.

Ramit Debnath

Ramit is among a handful of academics and researchers who are the forefront of a new, cutting-edge approach that involves the intermingling of various specialisatoins, which previously existed in their silos, to address and solve real-world problems. His area of work lies at the intersection of data science and public policy, using AI and Machine Learning to inform policy, mainly in terms of climate change and sustainability. He is also interested in exploring how decisions related to energy and climate justice are made at various levels: policymakers, large multinationals, communities, and individuals.

The Stanford Experiments

“I’m trained as an electrical engineer and moved from core engineering to public policy,” Ramit tells Global Indian. Born in Kolkata and raised in Arunachal Pradesh, Ramit’s career saw a major transition when he arrived to study at IIT-Bombay. “The course was called Technology and Development and it was about using engineering to influence policy for sustainable development,” he says. Soon after, he moved to Stanford University as a visiting researcher. His work has been varied, from working with low-income housing in India, Africa, and South America to analysing Twitter for climate misinformation. At every point, he realised, “The problem is connected with climate action.”

Starting in 2016, Ramit and his colleagues at Stanford University’s Civil and Environmental Engineering Department experimented with install temperature and humidity sensors in slums, “to understand the thermal comfort characteristics of people and how we can make informal settlements more liveable using data-driven design.” One technique involved building computer simulations to model thermal comfort in slums, “and trying to scale it up to a country scale. We studied between 10 and 20 slum houses and installed sensors to gather data over about three months. The idea was to create a robust simulation model and scale up from the micro level.”

A people-centric, sustainable approach to low-income housing

At Cambridge University, he continued to build on the work. “It’s where I started examining it through the angle of energy justice. I had realised that it was a socio-cultural problem and not just an engineering problem,” Ramit explains. The end goal for governments in developing countries – they studied India, Brazil, and Nigeria – is affordable housing for all. It’s a noble goal, no doubt but all three countries reflected one obstacle in common – rising energy costs. The nature and context of the problem is unique to each country, but the issue was the same.

In India, people in slum communities were organised according to a social structure that allowed people to share, especially electrical appliances. When they moved to vertical social housing structures, they became more individualistic and bought their own refrigerators, televisions, and so on, increasing energy costs. “The other reason, the ‘informal’ one, is informal businesses. People would set up welding shops and other businesses like that on the ground floors of the housing complexes. They use a tremendous amount of energy and require high-voltage transformers. These bills are added to household metres. It’s an informal spike in energy that is hard to quantify because nobody wants to reveal what’s happening.” The power distributors would also send bills once in several months, saddling the average, low-income household with an exorbitant sum that they had to pay, pronto. “This is why I call it an energy justice issue,” Ramit remarks.

The culture of sharing exists in Nigeria too, albeit very differently. Low-income communities exist in clusters on the outskirts, made up of daily wage and informal workers. “People use communal freezers to store their things, especially during summer. In Abuja, Nigeria’s capital city, if an appliance is damaged, the owners would have to travel far, to the city centre to get it fixed. “Usually, it means losing that day’s pay. There are also up to seven hours of load-shedding and lots of voltage spikes, so new appliances are damaged quickly.” Load-shedding is a problem in Brazil too, where the government runs a well-intentioned programme in which the rich donate used appliances that are distributed among low-income communities. “At every point, I would realise that energy and climate injustices were at the core of the problem.”

Net-zero futures at COP 26

Ramit then participated at COP 26, in the ‘Futures We Want’ workshop, a flagship programme by the UK government, in which people in six regions were asked to imagine a globally net-zero, climate-resilient future. “That exposed me to various cross-cutting themes, not just in terms of energy but also its implications in climate change and vulnerability. The India chapter includes declarations like, “By 2050, India will have shifted decisively away from fossil fuels. Local renewables generation, coupled with battery and hydrogen storage will give rural communities more autonomy.”

Agroforestry is also on the wish list, with the need for sustainable farming techniques that will protect the environment and also improve food security. “Traditional practices like rice-fish culture- rearing fish in rice paddies to eat pests and oxygenate water are likely to be more popular,” the website reads.

“In India, people were concerned about agriculture, worrying that India might not be able to produce enough food to meet the growing needs of the population,” Ramit explains. “Lack of rainfall and a rise in the frequency of drought is an effect of climate change. The land is also being flooded due to a rise in sea levels. how do we take these things into account?” Ramit worked with two professors, one from IIT-Delhi and another from B.R. Ambedkar University to write a policy brief on evidence of what India has in terms of climate vulnerability, looking at various sectors including agriculture, energy, water, food, and land, to try and connect the dots.

Climate-action and greenwashing

After this, Ramit shifted his focus to ‘climate action through net zero action’. When people talk about ‘climate action, what actions do they talk about’, he asks. “How can those systems be integrated into the current policy?” That’s the project he’s working on now and he uses Twitter to do so.

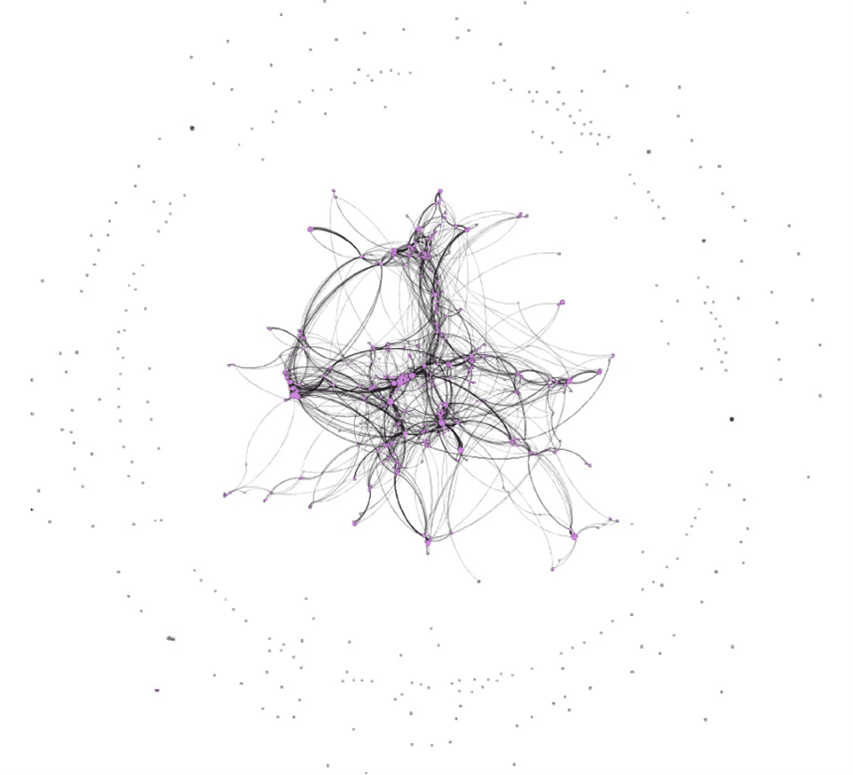

Graph showing network of Twitter interactions. Source: Cambridge Zero

Social media provides a very unique data set, it’s cross-sectional, spanning various geographies,” Ramit says. “How do people react to climate events, extreme weather events, and greenwashing?” I nudge him on the latter- the average social media user’s account is usually flooded with advertisements for consumer products trumpeting their sustainable practices. His answer is surprising. “Most greenwashing is popularly believed to come from fossil fuel firms,” he says. The term greenwashing, also known as ‘green sheen’, is a form of misleading advertising or marketing spin, in which green PR and green marketing are used deceptively. “A major company might be drilling for oil but they say they are creating economy or investing in green technology.”

Ramit uses machine learning and AI to take a people-centric point of view to climate action, examining “global Twitter accounts that are very public-facing,” he says. “How do they talk about climate change? What do fossil fuel firms talk about, versus governments and NGOs? What are the leading social media narratives?” From there, it leads naturally to how the stock markets affect these conversations, especially with fossil fuel firms. “Much of the misinformation is driven by investors,” he says.

Countering misinformation

At the same time, there also exists another end to climate action. One movement, Ramit says, is called Climate Repair, which involves a group of people claiming they can “intervene in the earth’s system and use technology to solve problems.” They talk of geo-engineering and solar-engineering, “like solar-radiation management with means spraying ions into the sky that reflect radiation, reducing the amount of radiation that space receives. It’s very controversial at the moment,” Ramit adds, “Because nobody knows what the impact of such measures will be. Say, if something is deployed in the UK (strictly hypothetical), will it impact India?” This end of the spectrum, Ramit explains, and anybody who disappeared into Twitter’s rabbit holes can probably confirm, leads to a whole other range of conspiracy theories, like ‘chem trails’, for instance.

What’s the end goal in all of this? “We’re trying to inform policymakers – the problem of energy justice and climate change is very real, as is that of misinformation,” Ramit explains. “We also want to work with platforms like Twitter and Google, how do they counter misinformation or climate change deniers?”