(November 24, 2023) A fresh ibex carcass was a tell-tale sign that a snow leopard was nearby. This was back in 2010, in South Gobi, Mongolia, where Dr Koustubh Sharma, the Conservation Science Director at the Snow Leopard Trust, stood with a team of seven researchers on a peninsula-shaped ridge line that dropped into a steep slope. It was mid-morning, though, an unlikely time for a snow-leopard sighting. As a colleague, Orjan, inched closer to examine the carcass, the snow leopard, which had been hiding just out of sight, jumped up on to the ledge to avoid him and found itself face-to-face with Koustubh. “He was so very surprised,” Koustubh laughs, as he recalls. “I still remember that look on his face, and all the scars he carried.” The snow leopard overcame its surprise and slunk away as quickly as it had appeared – Central Asia’s apex predator can also be quite shy. In fact, Koustubh says, there are hardly any known encounters where a snow leopard has deliberately attacked humans.

In the 15-odd years that Koustubh has worked on the conservation of the species, he has only seen it a handful of times in the wild. The animal’s elusive nature was part of what drew him to it. “People work with snow leopards for years and never get to see them,” he says. They melt into their terrain, making them very hard to spot and can survive in no-man’s land atop snow-covered mountains, breathing very scant air fairly comfortably.

A career in conservation

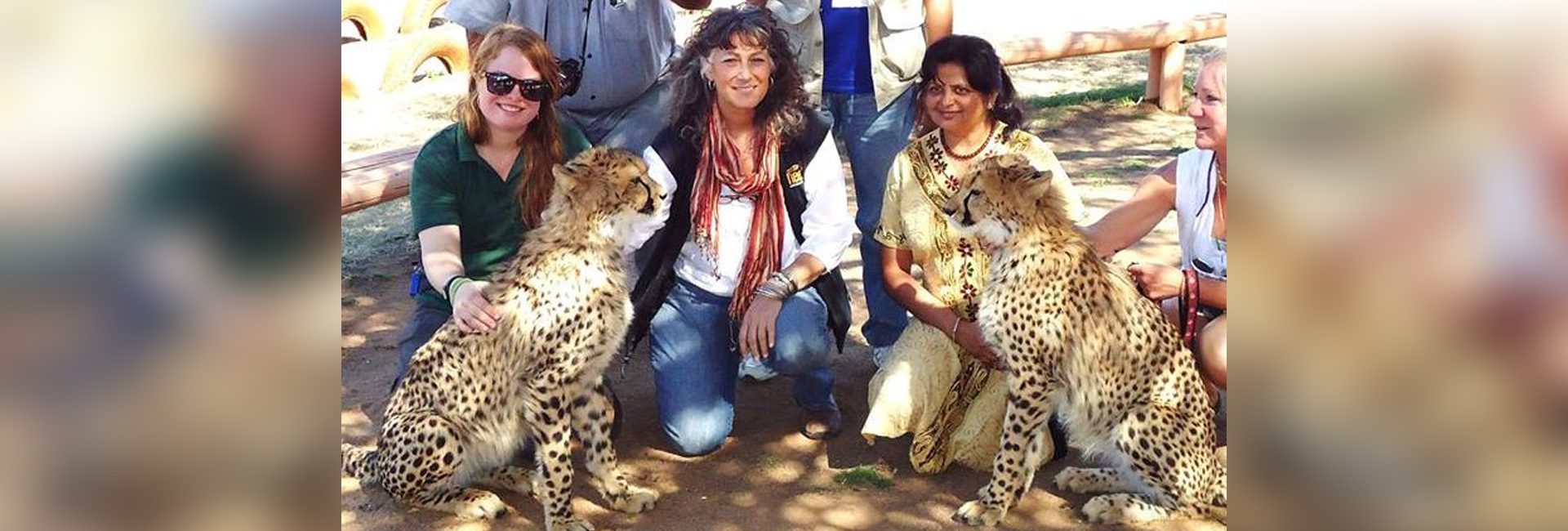

Dr Koustubh Sharma. Photo by Xavier Augustin

Koustubh speaks to Global Indian from Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, where he has been based since 2017, splitting his time between his role as International Coordinator at the Global Snow Leopard and Ecosystem Programme and as the Director for Science and Conservation at the Snow Leopard Trust. One of the species’ foremost researchers and conservationists, Koustubh’s work involves collaborating with policymakers, conservationists and organisations from snow leopard range countries. It means working with partner organisations and making sure that the research and field terms have all the support they need – in terms of scientific and financial resources. “There’s a lot of grant writing, outreach, communication and public speaking involved,” Koustubh explains. “And since a third of the world’s snow leopards live within 100km from international borders, you need to work with multiple governments.”

It also involves braving some of the world’s harshest terrains, usually in alpine and sub-alpine zones, at elevations of between 3000 and 4,500 meters above sea level. Snow leopards have a very broad range – their habitat extends thousands of kilometres across diverse and very rugged landscapes, across the mountainous regions of Central and South Asia, covering some 12 countries including Afghanistan, Bhutan, China, India, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia and Uzbekistan.

Tech as a gamechanger

A couple of decades ago, being a conservationist meant a lot of treacherous hikes to set up camera traps, and going back everyday to change film rolls and batteries. By 2004-2005, the technology had evolved to digital cameras and conservationists had to visit every six months to replace the battery, collect data and put the traps back. Today, technology has done away with the need to physically camp out in the bitter cold of the rugged Central Asian terrain.

Testing camera traps. Photo courtesy: Dr Koustubh Sharma

Bridging technology and conservation holds a deep fascination for Koustubh. He even appeared in a Microsoft ad, talking about how scientists at the Snow Leopard Trust use the MS’ AI tech in their research efforts. “To protect snow leopards, you need to know where they are,” he said. Camera traps capture thousands of images that need to be analysed – a task that means days of work for humans, and 10 minutes for an advanced AI.

From Bhopal to Bishkek

His association with the snow leopard feels like kismet – he was in the right place at the right time. After completing his Master’s in Physics, Koustubh moved to the Panna Tiger Reserve to do his PhD in wildlife zoology by studying the Four Horned Antelope. “Those were blissful times” he smiles. “I would go in the morning, observe the wildlife and come back. It was like earning for a hobby.” Spread out over 552 km of forestland, life at Panna was not for the faint of heart. “It can be quite intense if being alone scares you,” Koustubh agrees. He wasn’t one to scare easily though – in college, he had picked up bird watching, because it was something he could do in Bhopal. When an overhaul of one of the city’s lake required compiling bird data, Koustubh, who was a college kid then, was taken on for the project. “And that was how my association with the Bombay Natural History Society started too,” he says.

At the Panna Tiger Reserve, he met another scientist, Dr. Raghu Chundawat, who incidentally, is the first person to complete a PhD on snow leopards, back in the 1980s. Given his background in Physics, Koustubh was fairly comfortable with numbers and he collaborated with Dr Chundawat to explore and experiment on a few methods to monitor and assess snow leopards. They tried and tested site occupancy methods – which are techniques used to determine whether a particular area or site is occupied by a certain species. These methods, which involve camera traps, surveys for tracks, scat or markings and DNA samplings were all fairly new at the time.

As he wound up his thesis, Koustubh heard about the Snow Leopard Trust. Founded in 1981 by Helen Freeman, the Snow Leopard Trust is a non-profit dedicated to the conservation of the endangered snow leopard and the preservation of its ecosystem. They were looking for a regional field biologist, someone who could stay in a remote area without worrying too much about what was happening back home. They also wanted someone to help the researchers in study designs and data analysis. Koustubh was the man for the job.

Where the wild things are

That’s how Koustubh began his journeys through the wilderness of Central Asia. “My first trek was in -40 degrees,” he says, when he was tasked with setting up a base station site for the first ever long-term ecological study of snow leopards in Mongolia back in 2008. He took off from Delhi, with his overcoat in his main suitcase. As the plane landed, the pilot announced that the temperature was 35 degrees Celsius. “I was like, why is everyone panicking back home? I have lived through 45 degrees Celsius. I stepped out and felt like I was being pricked by thousands of needles. I hadn’t heard the ‘minus’. My colleagues still make fun of me,” he smiles.

Extreme weather is part of the deal, though. Snow leopards tend to live higher up in the mountains, usually above the treeline but just below where everything is totally frozen. “It is the only species that is found only in the mountains.” Since prey is scarce so high up in the mountains, snow leopards wander extraordinary distances in search of food, accounting for their large home ranges. Creating and preserving a habitat is challenging, because it spans several thousands of square kilometres. “So, we work with people whose spaces overlap with the snow leopards,” Koustubh explains.

Community-driven conservation

Such a large home range means snow leopard territories often overlap with that of humans. With a global population of a few thousand mature individuals, which is projected to decrease by about 10 percent by 2040, the snow leopard faces significant threats from poaching and as mentioned already, the loss of habitat due to infrastructural expansion. “So by design, all conservation work is about community engagement,” Koustubh explains, adding, “By building partnerships with local communities, understanding challenges that snow leopards face and coming up with mutually agreeable solutions for people and animals alike.” Humans are the main threat to snow leopards, which attack their livestock – and their livelihoods. “We have developed community-owned insurance programmes that helps protect villagers from the onslaught of loss.”

Simply put, if people are losing their livestock already to disease, and then one is killed by a snow leopard or a wolf, they’re going to want to take their frustration out on the predator. If farmers are losing fewer livestock, they can better withstand the loss of one or two. “In some areas we even work with communities by helping them develop handicraft products. We also help them produce honey, and initiate tourism programmes.” Happy tourists can go a long way towards protecting the snow leopard, Koustubh says. “We have another programme to help communities build sustainable and conservation-oriented tourism.” At the end of the day, Koustubh says, there’s no replacing local skills. “You can bring in your skills and compliment them.”

When he’s not working, Koustubh is out stargazing on clear nights in Bishkek, to pursue his “rekindled childhood hobby” of astrophotography. I spot some equipment in the background as we speak. “I use a 70-200mm and 400mm standard canon lenses, Schmidt–Cassegrain catadioptric telescope, Doublet Refractor telescope and Newtonian telescope to photograph the night sky,” he explains. His Instagram profile is peppered with pictures of Orion’s Belt and the Horsehead Nebula, which appear to hold a certain fascination for him.

View this post on Instagram

Dr. Koustubh Sharma’s work in snow leopard conservation bridges gaps between science, policy, and community, shaping a future where both humans and these elusive cats can thrive. His journey underscores the importance of perseverance and collaboration in the face of environmental challenges.

- Follow Dr Koustubh Sharma on Instagram

Also Read: Wildlife, Fossils, and Policy: Anjali Goswami to join UK’s Defra as Chief Scientific Adviser

Also Read: Venkatesh Charloo: How a banker in Hong Kong returned to India to conserve marine life

Also Read: Afforestt: Shubhendu Sharma shows you how to grow a 100-year old forest in 10 years

Koustubh is such a great Mentor. I was fortunate to have interacted on some occasions while he was helping us and the children on a trip to understand Nature’s wonders in the Central Indian Highlands.