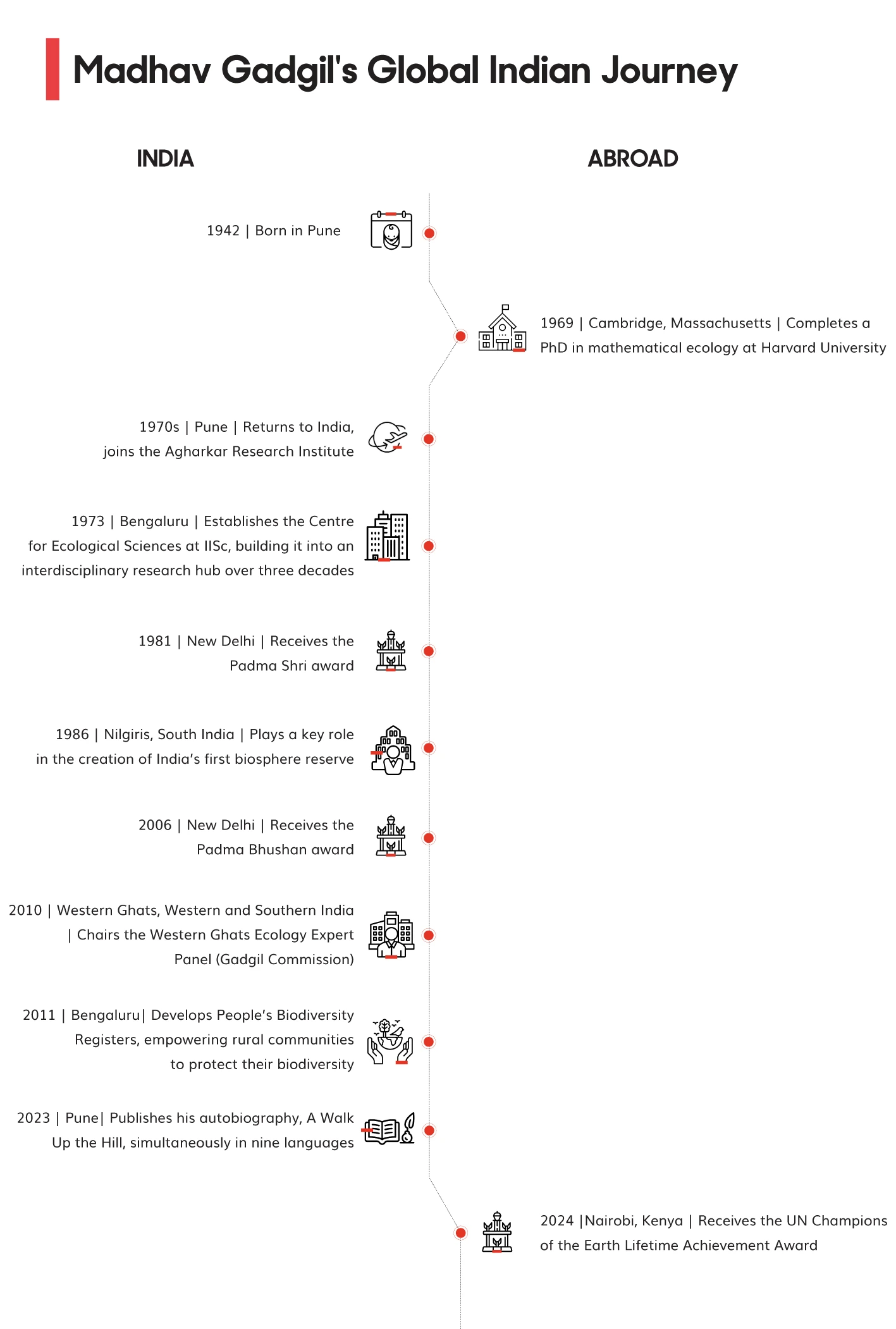

(December 18, 2024) Madhav Dhananjaya Gadgil, one of India’s most celebrated ecologists has received the 2024 United Nations’ Champions of the Earth Lifetime Achievement Award—one of United Nation’s top honours, for decades of dedication to community led environmental conservation in India. “This is a validation of the idea that people and nature must coexist, and that science can thrive alongside local knowledge,” Gadgil remarked following the announcement.

Despite being a Harvard PhD graduate in the late 1960s, when most Indian students preferred to stay abroad, Gadgil made the resolute decision to return to India. While his peers pursued careers in prestigious Western institutions, Gadgil chose a path of returning to India’s underfunded academic environment in the 1970s, driven by a vision to integrate ecological science with local wisdom. “The idea of field ecology fascinated me,” he shared. “I wanted to explore and contribute to the landscapes that shaped me.”

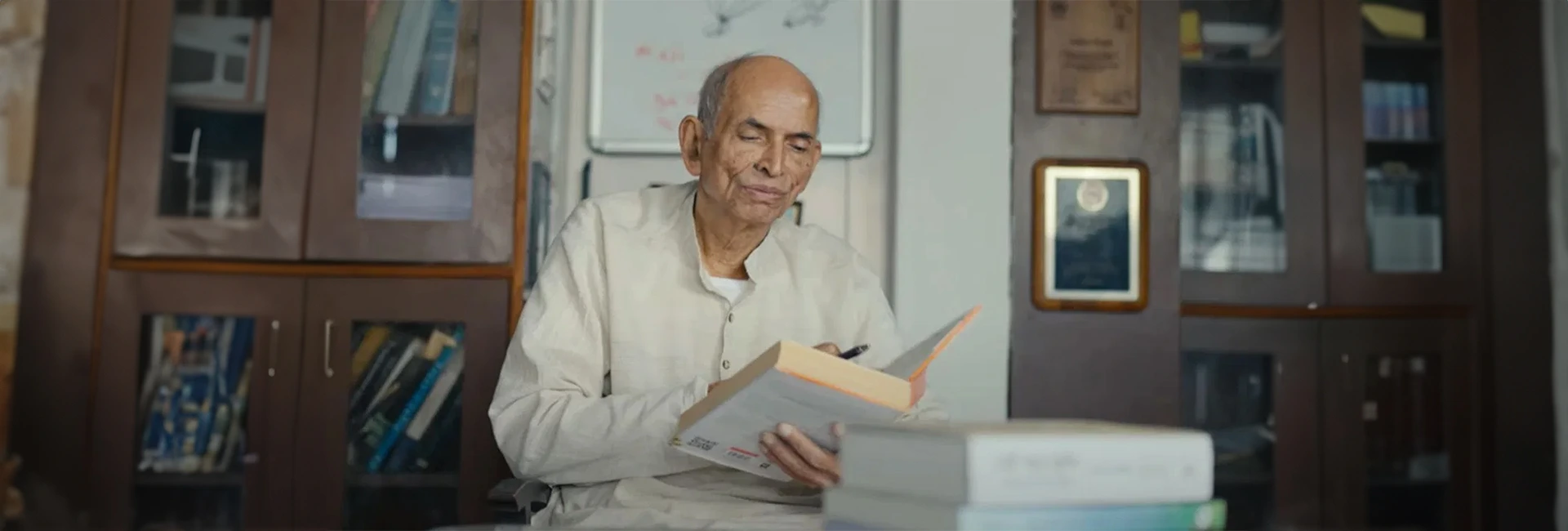

Madhav Gadgil | Photo Credit: Sanjoy Ghosh

Shaping India’s green future

Gadgil’s work has had a powerful impact on India, shaping policies and practices in environmental conservation. From pioneering India’s first biosphere reserves to advocating for People’s Biodiversity Registers (PBRs), his initiatives have empowered local communities to become stewards of their natural heritage. His leadership on the Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel brought ecological sensitivity into national discussions, influencing both government policy and public awareness.

Recognizing his extraordinary contributions, the Government of India had awarded him the Padma Shri in 1981 and the Padma Bhushan in 2006, acknowledging his role as a transformative figure in Indian environmental science. Gadgil’s efforts have not only preserved critical ecosystems but also inspired a generation of ecologists and conservationists to adopt inclusive, community-driven approaches.

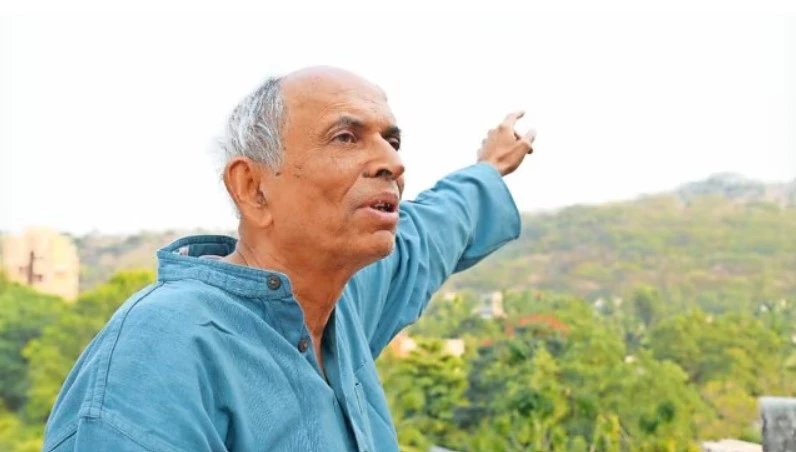

Madhav Gadgil

The early years: Seeds of curiosity

Born in Pune in 1942 to an illustrious family, Gadgil’s father, Dhananjaya Gadgil, was a prominent economist and creator of the “Gadgil Formula” for resource allocation. Influences from his father’s interests and interactions with luminaries like ornithologist Salim Ali and sociologist Iravati Karve shaped his childhood. Gadgil’s curiosity about nature was sparked early when he wrote to Salim Ali with questions about bird moulting. To his amazement, Ali replied with detailed explanations, encouraging the budding scientist. “It was a transformative moment,” Gadgil said, “to see someone so accomplished take time to mentor a curious teenager.”

Gadgil also credits his upbringing in Pune, surrounded by the Western Ghats, as pivotal. “The Ghats were my first love,” he said, “a place where my fascination with biodiversity and human interaction with nature began.” His early treks with his father, observing forests, birds, and rural life, planted the seeds for his lifelong commitment to ecology and social justice.

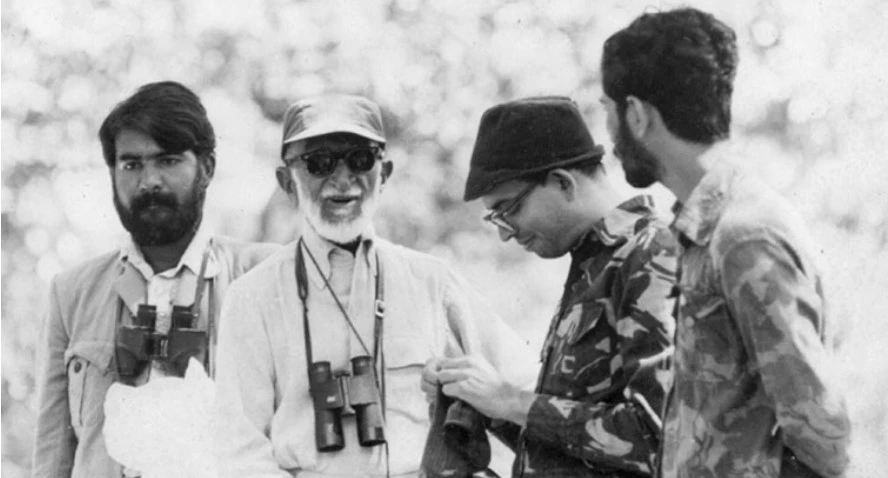

Gadgil with ornithologist Salim Ali Bandipur National Park in Karnataka in 1977 | Madhav Gadgil Archives

Harvard and the road home

At Harvard University, Gadgil explored mathematical ecology under the guidance of professors William Bossert and E.O. Wilson, graduating with a PhD in 1969. Harvard’s rigorous academic culture and opportunities to collaborate with prominent scientists like Paul Ehrlich and Jared Diamond left an indelible mark on him. Yet, the pull of India remained strong. “I saw science as a means to address real-world problems,” he explained, “and I wanted to contribute to India’s ecological and social landscapes.”

Rejecting lucrative offers at Harvard and Princeton, Gadgil returned to India upon completion of his PhD. He joined the Agharkar Research Institute in Pune, where he initiated research on sacred groves—traditional forest areas preserved by local communities. Gadgil’s observations contradicted the prevalent belief that conservation was purely religious. Instead, he demonstrated that sacred groves were valued for the ecological services they provided, such as water conservation. This early work laid the foundation for his later advocacy of community-led conservation.

Gadgil at his ancestral home in Pune | Photo Credit: Sanjoy Ghosh

Pioneering contributions at IISc

In 1973, Gadgil joined the Indian Institute of Science (IISc), Bengaluru, where he founded the Centre for Ecological Sciences (CES). Over three decades, he built CES into a hub of interdisciplinary ecological research. Gadgil’s work ranged from quantitative studies of ecosystems to using advanced tools like remote sensing. “The IISc’s interdisciplinary ethos allowed me to bring together ecologists, engineers, and statisticians under one roof,” he recalled.

A landmark achievement during this period was the establishment of India’s first biosphere reserve in the Nilgiris in 1986. Gadgil advocated for an inclusive conservation model that integrated local communities—an approach inspired by UNESCO’s biosphere reserve framework. “Protecting nature isn’t about excluding people; it’s about working with them,” he explained. This philosophy, though unconventional at the time, would become a hallmark of his work.

Another of Gadgil’s groundbreaking initiatives was the development of People’s Biodiversity Registers (PBRs), which enabled communities to document and protect their local biodiversity. “The PBRs gave villagers a sense of ownership over their ecological heritage,” Gadgil said, “and empowered them to challenge destructive policies and practices.”

The Gadgil Commission: Controversy and vision

In 2010, Gadgil was appointed as the chair of the Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel (WGEEP), tasked with identifying ecologically sensitive zones in the Western Ghats, a biodiversity hotspot. The panel’s 2011 report recommended designating 64 percent of the region as an Ecologically Sensitive Area (ESA), balancing conservation with sustainable development.

However, the report sparked fierce debate. While environmentalists lauded its scientific rigour, state governments and interest groups opposed it, fearing economic losses. Gadgil’s commitment to grassroots participation—organizing village meetings and essay competitions for schoolchildren to understand local perspectives—was both praised and criticized. “We put people at the heart of conservation,” he stated, “even if it ruffled feathers.”

The rejection of the report’s recommendations didn’t deter Gadgil. In 2018, devastating floods in Kerala reignited discussions around the report, with many citing its unheeded warnings. “Science cannot serve the vested interests of a few,” Gadgil asserted, “it must serve the people and the planet.”

Writing for change

A prolific writer, Gadgil has authored over 250 scientific papers and numerous books, including This Fissured Land and Ecological Journeys. He also wrote extensively in Marathi, bridging the gap between science and society. “Writing in regional languages brought my work closer to the people,” he shared, recounting letters he received from farmers and craftsmen inspired by his articles.

In 2023, Gadgil published his autobiography, A Walk Up the Hill: Living with People and Nature, simultaneously in nine languages. Reflecting on his journey, he said, “The book is not just about my work but about the people, landscapes, and cultures that shaped me.”

Gadgil’s ability to connect with a wide audience, from academics to rural communities, has been instrumental in his success. His writings often highlight the symbiotic relationship between humans and ecosystems, challenging the notion that conservation must come at the cost of development.

An enduring legacy

Throughout his career, Madhav Gadgil championed the integration of traditional knowledge with scientific research. His work on People’s Biodiversity Registers empowered communities to document their ecological heritage, ensuring grassroots participation in conservation. His advocacy for equitable resource management has inspired policies worldwide.

Even in retirement, Gadgil’s optimism remains undiminished. “I see hope in the implementation of community forest rights,” he remarked. “When people reclaim their connection with nature, ecological prudence follows.”

Gadgil’s influence extends beyond academia. His mentorship has shaped a generation of ecologists, many of whom carry forward his vision of community-driven conservation. He taught his students to look at local communities as allies, not adversaries, in the fight to protect nature.

A life well-lived

When asked if he made sacrifices by choosing a less lucrative path, and returning back to India after a Harvard education, Gadgil smiled. “I have made no sacrifices,” he said. “Every challenge, every climb, whether literal or metaphorical, has been a joy. To live amidst India’s landscapes and its people has been the greatest privilege of my life.”

Madhav Gadgil’s life exemplifies the power of staying rooted while reaching for global heights—a reminder that the greatest impact often comes from those who choose to serve their own soil.

- Discover more fascinating Stories