(February 17, 2024) While the effects of AI on health and work-life balance are receiving widespread attention, snakebites continue to be a neglected public health issue. WHO estimates about five million snakebite occurrences in India annually leading to nearly 2.7 million envenomings (a life-threatening disease caused by snake venoms). These incidents lead to somewhere between 81,000 and 138,000 deaths annually in the country. Snakebite envenoming also causes up to 400,000 cases of amputation and other permanent disabilities. American by birth and Indian at heart, herpetologist and conservationist Romulus Whitaker is one of the few individuals who has dedicated his life to addressing this problem.

Born in New York in 1943, Whitaker arrived in India as an eight-year-old. He fell in love with the country and made it home. Driven by his deep passion for wildlife, he embarked on a life-long journey dedicated to the study and conservation of India’s reptiles, establishing himself as a herpetologist and conservationist. Over the years, he has made invaluable contributions to wildlife research and nature conservation in India, and has pioneered several significant projects. He established the Madras Snake Park in 1969, the The Madras Crocodile Bank Trust in 1976, the Andamans Centre of Island Ecology in 1989, and the Agumbe Rainforest Research Station in 2005. His contributions have been recognised with prestigious awards, including the Whitley Award, Rolex Award, Order of Golden Ark, Peter Scott Award, Salim Ali Award, and the Padma Shri.

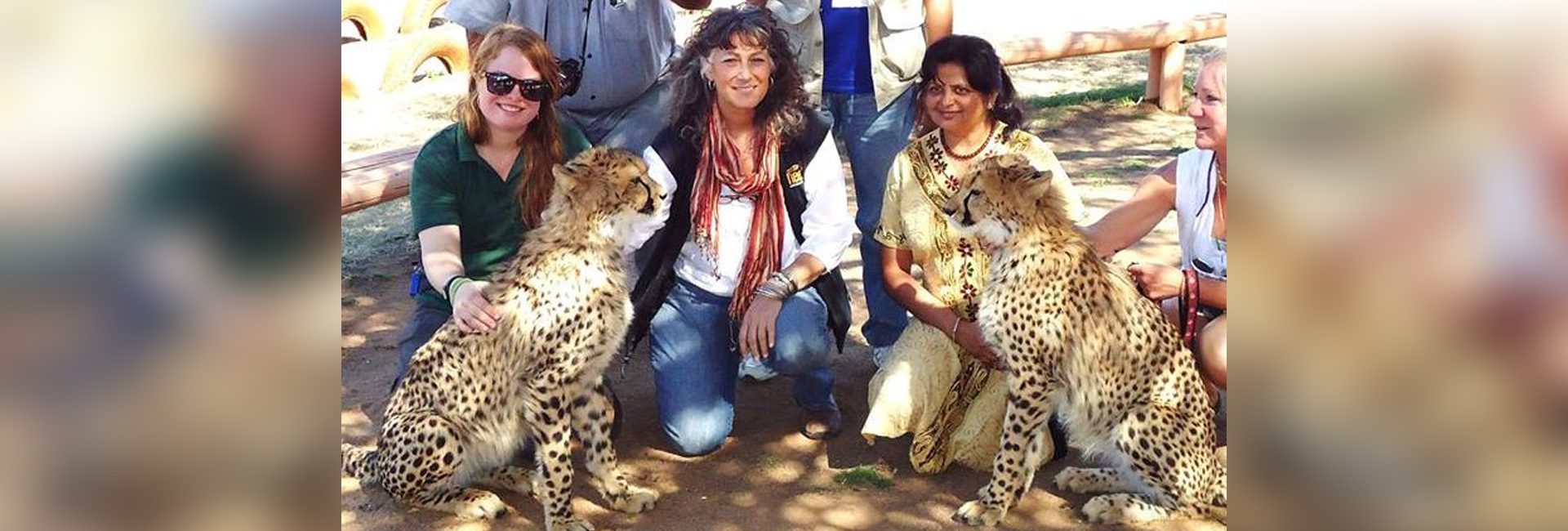

Romulus Whitaker

Two species, Eryx whitakeri, a type of Indian boa, and Bungarus romulusi, a species of krait, are named after Whitaker. In addition to penning numerous technical papers and books, such as ‘Snakes of India: The Field Guide,’ Whitaker has directed and produced several wildlife documentaries, including the Emmy Award-winning ‘The King and I,’ that explores the natural history of the king cobra, the largest venomous snake in the world. Acclaimed as the ‘Snakeman of India,’ Whitaker is professionally affiliated with multiple organisations working towards wildlife conservation across the world. Fluent in Tamil and Hindi, Whitaker has recently released the first volume of his three-part memoir, ‘Snakes, Drugs and Rock ‘n’ Roll: My Early Years,’ published by Harper Collins and co-authored by Janaki Lenin.

Addressing the ‘poor man’s disease’

For decades, Romulus Whitaker and his team have been dedicated to addressing snakebite issues in India. Referred to as a ‘poor man’s disease,’ it not only causes physical harm to its victims but also places a considerable burden on their families, as those affected are predominantly individuals employed in agricultural settings.

Dealing with snakebites in rural areas is tough. Awareness is crucial, especially about medically important venomous snakes like the spectacled cobra, Russell’s viper, common krait, and saw-scaled viper, most commonly found across the geographical region.

– Romulus Whitaker

Romulus Whitaker

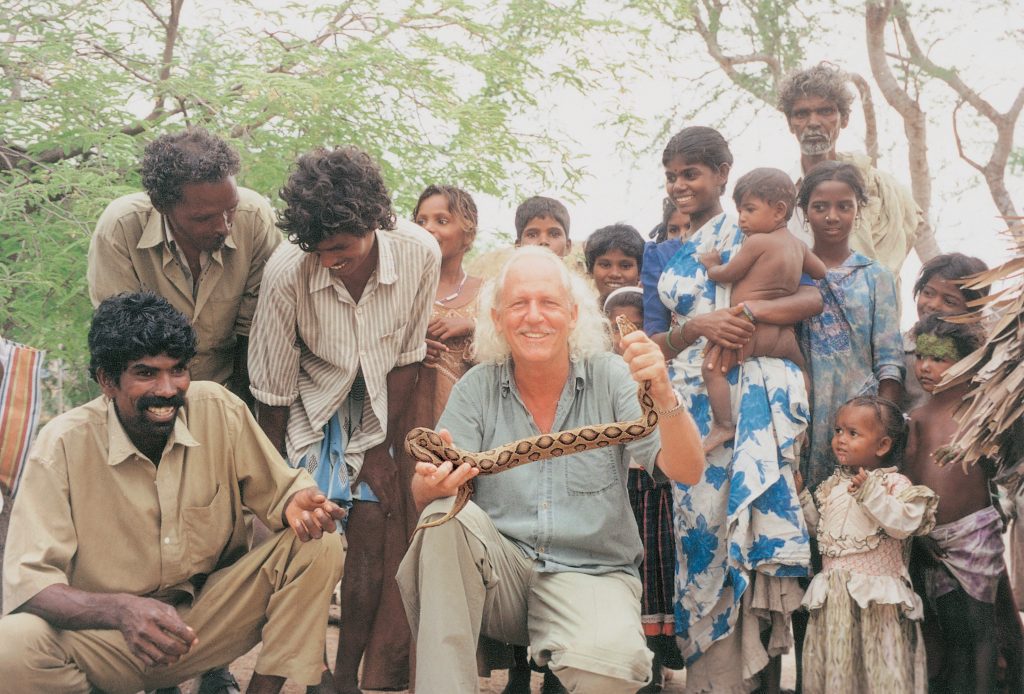

Over the years, Whitaker has worked towards educating rural communities on snakebite prevention, providing guidance on safety protocols, and aiding in the identification of the four most dangerous snake species. Through workshops conducted for local rescuers, forest departments, and fire departments, Whitaker and his team have strived to minimise human-snake conflicts and ensure the safety of all involved.

Improving rural healthcare access

“Dealing with snakebites in rural areas is tough. Lack of healthcare means victims often don’t make it to a hospital on time. With so many snake species, identifying the dangerous ones is tricky,” Whitaker mentions in one of his blogs. “People sometimes go to traditional healers, and transportation issues delay treatment. On top of that, different venom types and a lack of trust in healthcare workers make things even more complicated. Sadly, snakebite isn’t a priority in many hospitals, and healthcare workers often need proper training,” he adds.

Whitaker and his team collaborate with regional, national, and international organisations, including US-based Global Snakebite Initiative (GSI) that aims to improve the quality, effectiveness, and accessibility of treatment options globally.

Romulus Whitaker with tribals

“We are also training ASHA workers and health staff to boost their confidence in administering antivenom (AV). Some hesitate due to the risk of allergic reactions from antivenoms. We are collaborating with researchers to develop better antivenoms, not only to reduce reactions but also to make it region-specific,” he mentions.

Recognising the under-reporting of snakebite incidents, Whitaker and his team are advocating for a snakebite registry and are involved in developing regional, state, and national strategies to address the problem comprehensively.

Developing friendship with snakes

Growing up in the countryside of northern New York State, Whitaker developed a fascination for snakes, in the way most children have a fondness for toys. Rather than discouraging his fascination, his mother actively supported his interest by even allowing him to bring snakes home, taking him to the Natural History Museum in NYC, and getting him books about snakes.

At the age of eight, in 1951, when Whitaker relocated from the USA to India with his mother Doris Norden, and stepfather Rama Chattopadhyaya, he was instantly captivated by the warmth of the people. He studied in Kodaikanal, where he cultivated a deep appreciation for the natural world through explorations in the forests of the Palni Hills.

Romulus Whitaker with school kids

In 1961 he went to the U.S. for higher education, and briefly served in the U.S. Merchant Navy before joining the Miami Serpentarium, where he met his mentor William Haast and gained expertise in venom collection. Whitaker’s deep love for India compelled him to return in 1967.

Becoming central figure in snake and crocodile conservation

Upon his return, he was introduced to the Irula tribe, renowned for their snake-catching abilities. He discovered they were misusing these skills. “They were amazing at catching snakes, but sadly, they were misusing their skills in the snake-skin industry,” Whitaker says. This prompted him to establish a snake park for their welfare. His initiatives coincided with the government’s efforts to ban exploitative activities involving snakes.

My early days with snakes taught me we needed to change how people see them.

– Romulus Whitaker

In 1969, Whitaker established a snake park near Madras, employing Irulas as caretakers to alter their relationship with snakes. By 1971, with assistance from the chief conservator of forests, the park was relocated to the Guindy Deer Park in the city, attracting a million visitors in its inaugural year.

During the mid-1970s, he collaborated with his ex-wife, Zai Whitaker, to launch the Madras Crocodile Bank Trust near Mahabalipuram’s Shore Temple – significant initiative in crocodile conservation and now a premier attraction in Chennai. Also known as the Centre for Herpetology, crocodiles are bred in captivity there with the purpose of releasing them into the wild.

Romulus Whitaker

For me, it wasn’t just about saving the animals from the destruction we humans were causing in trying to get our resources; it was also about preserving nature’s balance by protecting its habitat. Because caring for the environment and its animals benefits us as well.”

– Romulus Whitaker

Over the next seven decades, Whitaker developed deep interest in two of India’s iconic reptiles, the gharial crocodile from the northern rivers and the king cobra from the southern rainforest.

Transforming snake hunters to snake protectors

Recognising the need to provide the Irula Tribe with sustainable livelihoods, Whitaker founded the Irula Snake-Catchers Cooperative in 1978. This cooperative transformed snake-catching into a humane practice, focusing solely on venom extraction, with released snakes returning to the wild. Today, the cooperative supplies 80% of India’s snake venom for antivenom production, saving countless lives across the nation, while the Irula tribals are engaged in dignified livelihoods.

Man of many achievements

Deeply committed to wildlife, in 1986, at the age of 43, Whitaker obtained a B.Sc. in wildlife management from Pacific Western University. He was appointed as a wildlife consultant by the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization which led him to provide his expertise in Papua New Guinea, Mozambique, Malaysia, Bangladesh, and Indonesia. He also served as the vice-chairman of the Crocodile Specialist Group under the IUCN/Species Survival Commission, and led efforts to rescue the gharial from the verge of extinction.

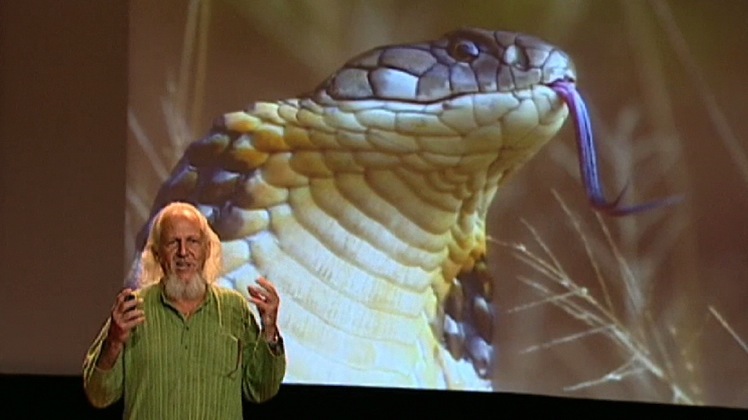

Romulus Whitaker during a talk

“I am happiest out in the wild just watching turtles, snakes, crocs and other herps,” tells the herpetologist, conservationist, wildlife researcher, filmmaker and author whose life revolves around wildlife.