(August 7, 2024) In 2010, Shubhendu Sharma decided to try something in his backyard. He cleared the grass from the 75-sq metre space, in Kashipur, Uttarakhand. Shubhendu began with the soil, making sure that it could hold moisture and nutrients. Then, he planted over 200 saplings, all of them native to the area, comprising around 19 species of shrubs and trees like timber, guava, and mulberry. In a couple of years, the shrubs and trees were growing tall and thick, the dead leaves would decompose into humus and convert to nutrients, as the forest became a single, living, breathing organism that can regenerate forever. This is the Miyawaki Method, named after Japanese botanist Akira Miyawaki, one of Shubhendu’s teachers and his great inspiration. Now, as the founder of Afforestt, Shubhendu takes inspiration from the Miyawaki Method to grow mini forests in homes, schools, factories and open spaces, creating 75 forests in 25 cities across the world, including the USA, Netherlands, Singapore, Pakistan and India.

The forest in Shubhendu’s backyard. Photo: Afforest

Afforestation is not as simple as planting a bunch of trees. A forest functions as a single organism made up of trees, shrubs, herbs, fungi and million sof other organisms, all of which interact with each other and their surroundings. But until 2009, Shubhendu Sharma had not thought about all these things. Growing up in Nainital, he loved machines and how they work, and wanted to be a engineer. He followed through on his dream, graduating with a degree in engineering and landing a job at the top company on his list – Toyota, where he specialised at making cars. He learned how to convert natural resources into products, how sap was dripped out of the acacia tree and converted to rubber to make tyres. “We separate elements from nature and convert them into an irreversible state. That’s industrial production. Nature, on the other hand, works by bringing elements together, atom by atom.”

Then, in 2009, Toyota invited Japanese botanist Akira Miyawaki to plant a forest at their factory, Miyawaki’s first forest in India. “I was so fascinated just by looking at pictures of his work in his presentation that I joined his team as a volunteer,” says the Global Indian. “I learned the methodology and like any engineer, I wrote a standard operating procedure on how to make a forest.” He volunteered at the afforestation of the Toyota factory, and for the next year and a half, observed, studied and wrote manuals on the Miyawaki Method.

The Miyawaki method: A deep dive

Miyawaki believed that if a land is deprived of human intervention, the forest will return to it. This begins with grasses, then small shrubs, trees that are pioneer species, usually soft wood that are fast growing, and finally slow growing trees like oak start to appear, Shubhendu explains.

Visual credit: Shubhendu Sharma | TED

“To make a forest, we start with soil. We touch, feel and even taste it to identify w hat it lacks.” Soil that is too compact won’t allow water to seep in and is mixed with locally available biomass, like peet, so the soil can absorb water and remain moist.” Plants need water, sunlight and nutrition to grow. If the soil doesn’t have nutrients, they don’t just add them. Instead, they add micro organisms to the soil which feed on the biomass, multiply and produce nutrients for the soil.

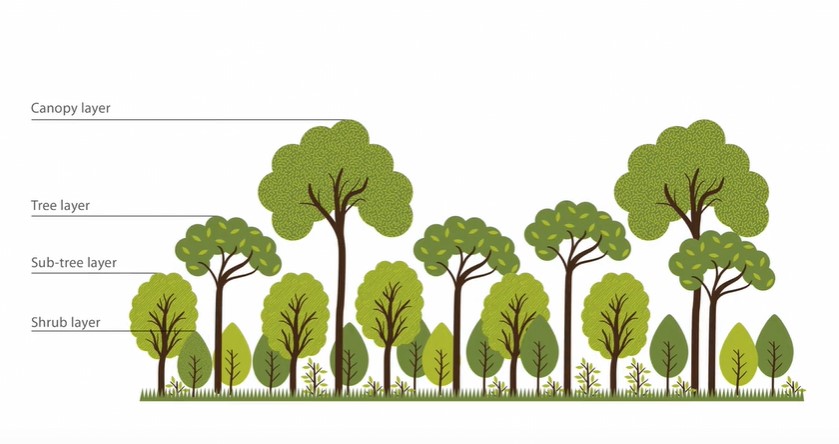

The other important thing is to use only native species. “What existed before human intervention is native,” Shubhendu explains. They survey national parks and reserves to find the last remains of a forest, the sacred grooves and forests around old temples. If they don’t find anything they visit museums to identify the species that belong there. “Then we identify the layers – shrubs, sub-tree, tree and canopy.” They sometimes make fruit bearing and flowering forests, those that attract a lot of birds and bees, or simply a native, wild evergreen forest. “We collect the trees and germinate the saplings and make sure the trees belonging to the same layer are not planted side by side or they will fight with each other for sunlight.”

Finally, on the surface of the soil goes a thick layer of mulch, so the soil can stay moist when it is cold, and remain protected from frost in the winter. Even while it’s freezing outside, Shubhendu says, “the soil is so soft that roots can penetrate rapidly.”

How does the forest grow?

In the first three months, roots reach a depth of 1 meter. These roots form a mesh, tightly holding the soil. Microbes and fungi live through this network of roots. “If nutrition is not available in the vicinity of a tree, these microbes will bring the nutrition to it.,” says Shubhendu. Whenever it rains, mushrooms appear overnight. This means that the soil below has a healthy fungal network. Once these roots are established, the forest grows on the surface.

Shubhendu Sharma

“As it grows, for the next two or three years, we water the forest,” he says. “We want to keep all the soil and nutrition only for the trees.” As the forest grows, it blocks the sunlight. Eventually, it becomes so dense that sunlight can’t reach the ground anymore. Weeds cannot grow because they need sunlight too. At this stage, every drop of rainwater that falls into the forest doesn’t evaporate back into the atmosphere. This dense forest condenses moist air and retains the moisture.

“Eventually, we stop watering the forest, and even without watering it, the floor stays moist, sometimes dark,” Shubhendu says. When a leaf falls on the forest floor and starts decaying, this decaying biomass forms humus, which is food for the forest. As the forest grows, more leaves fall, so that means more humus, more food, and the forest keeps growing exponentially. Once established, the forests will regenerate again and again, probably forever. In a natural forest like this, no management is the best management. “It’s a tiny jungle party. This forest grows as a collective. If the same trees, the same species had been planted independently, it won’t grow so fast. And this is how we create a 100-year-old forest in just 10 years.”

- Learn more about Afforestt on their website.