(May 21, 2022) Damp and derelict, the glint of out-of-use metal cutting machines cluttering its dark corners, the basement had a distinctly industrial air, when filmmaker Shaunak Sen first visited the place back in early 2019. Creating an unexpected scene of tenderness in this otherwise cold, decrepit space, Mohammad Saud and Nadeem Shehzad sat huddled in an inside room, tending to an injured bird. The brothers were whom Shaunak had come to see, having heard of their remarkable work saving scores of black kites in Delhi every day. Upstairs, the terrace held an even more surreal scene. In a giant enclosure overlooking a sea of blackened rooftops, hundreds of black kites waited to be set free when their wounds healed. Shaunak Sen’s All That Breathes is the story of these two brothers and their remarkable acts of kindness in an otherwise unforgiving city, where rats, cows, crows, dogs and people all jostle for space and survival. Scheduled to be screened at the 2022, Cannes Film Festival, the first Indian documentary to do so, All That Breathes will be part of the Special Screening Segment this week. It is also the first film to win the Grand Jury Award at the Sundance Film Festival earlier this year. On May 20, HBO announced that it will acquire worldwide television rights for the film.

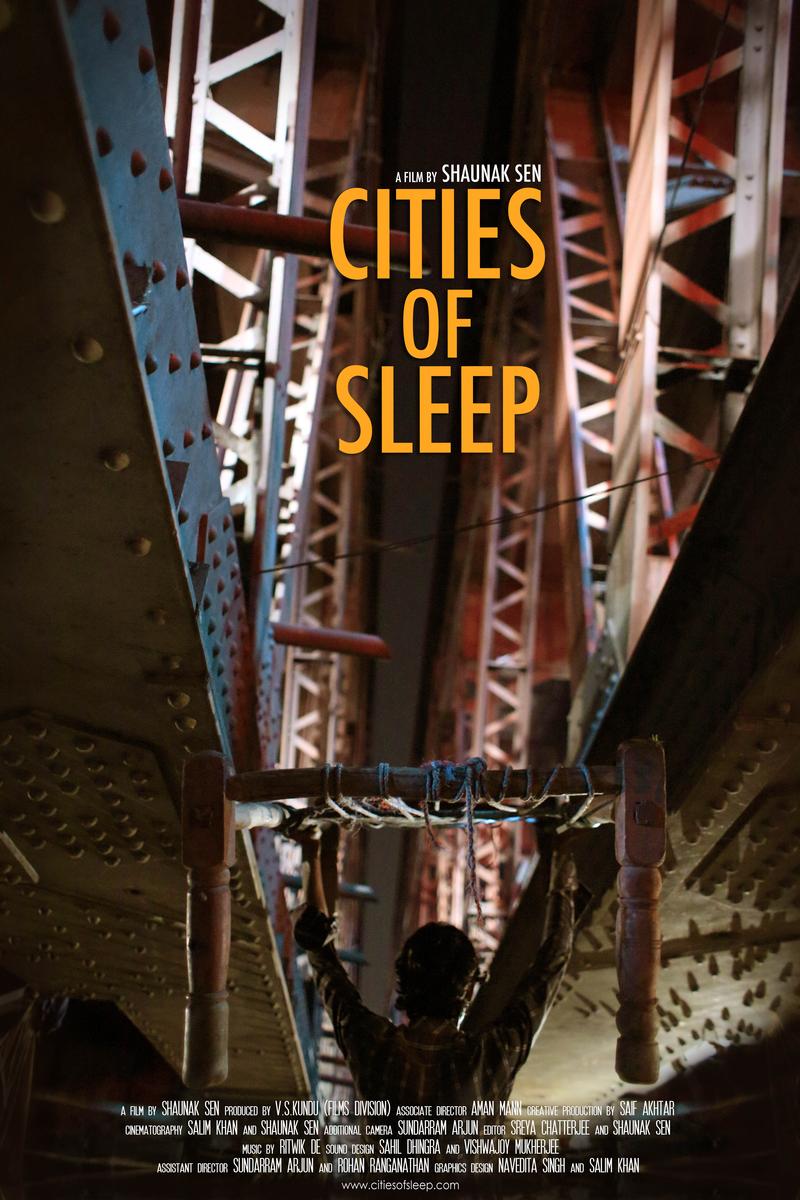

Shaunak is among a slowly growing but still small coterie of documentary filmmakers putting India on the world map. A steady rise is evident, with films like Writing With Fire and House of Secrets: The Burari Deaths capturing mainstream audiences from around the world. “I say this with guarded optimism but I think the Indian non-fiction circuit has fared better over the last few years than the fiction films,” Shaunak says, in an exclusive interview with Global Indian. Shaunak’s 2015 debut documentary, Cities of Sleep, was shown at over 25 international festivals and won six awards.

The world of narratives and storytelling

“For as long as I can remember, I cannot recall a time when I wasn’t interested in making films.” As kids, when he and his classmates were asked to write essays about what they want to be, Shaunak would talk of theatre and film. “Even in school, there was an inherent obsession with reading,” Shaunak says, which translated into a general love for narratives and storytelling.

Bluebells, the school Shaunak went to in Delhi, encouraged students to participate in extra-curricular activities, giving them a rich selection of choices. Shaunak was drawn to theatre, debates and quizzes, “the whole gamut of what makes up ECA in Delhi. I was interested in all of it.” Graduating with English honours from Delhi University, Shaunak threw himself full-time into the “world of narratives” as he puts it. Kirori Mal College’s theatre society was well known, “an old and hallowed group,” he says. Being part of the society was a formative experience, “Rigour and precision were expected of all of us in the group.” He did his masters in filmmaking at Jamia Millia Islamia and a PhD from JNU.

Shaunak Sen

Delhi’s ‘renegade sleepers’

Shaunak has always had trouble sleeping. “I have had intense patches of insomnia,” he says and from there grew an organic intrigue with the subject of sleep. “I chanced upon a text, Jacques Ranciere’s Nights of Labour, which looks at sleep through a different socio-political lens,” he says. From there began a series of visits to night shelters in Delhi, as Shaunak explored the idea of an urban space through the lens of its “renegade sleepers.” From this emerged Cities of Sleep, Shaunak’s debut documentary film, a portrait of Delhi through the eyes of people who sleep on its streets.

Delhi is home to some two million homeless people, according to the official figures. Many believe the real number is almost double. “The night shelters can only house an infinitesimal fraction of the total number of homeless people,” Shaunak says. But everybody needs to sleep and hundreds of informal, slapdash businesses have sprung up to cater to the swathes of homeless people. “Sleep infrastructure,” including bedsheets, blankets and maybe even a bed, are provided at nominal rates – and business is thriving. They have been somewhat unthinkingly dubbed ‘the sleep mafia’ by the media, a term that Shaunak confesses makes him “a bit uneasy.”

Made by a young team and shot on a proverbial shoestring budget, Cities of Sleep was a critical success, making its international debut at DOK Leipzig in Germany. It was also named the Best Documentary at the Seattle South Asian Film Festival.

All That Breathes

In All That Breathes, Shaunak paints what he calls “a dystopian picture postcard of Delhi in the 1990s.” “My first sense of tone was the sense we always have in Delhi, of gray, hazy skies and air purifiers humming everywhere. And in this all-encompassing grey, monotony, you can see birds flying around.” Mohammad and Nadeem presented a compelling story, driving what is otherwise a silent lament for a city in tatters.

The idea had begun a few months prior, around the end of 2018, when Shaunak was in the midst of a short-term Charles Wallace Fellowship at Cambridge University. There, housed in the department of Geography, he was surrounded by people working on different kinds of human-animal relationships. Working with his interlocutor, Dr Mann Baruah, the concept first entered his “philosophical ambit” at the end of 2018.

Such a long journey

The film involved nearly three years of shooting. “These films take long to make anyway. The idea is for the characters to get comfortable enough for the director to capture a sense of tone. You want the viewers to understand the passage of time, the quality of everyday life, to pick up on the emotions the filmmaker is putting out,” says Shaunak.

A still from ‘All That Breathes’

He headed to Copenhagen for the final cut, where he sought out editor Charlotte Munch Bengsten. In Denmark with his co-editor Vedant Joshi, Shaunak received the news that the film had got through at the Sundance Festival, the world’s largest platform of its kind, for 2022. “We worked feverishly to make it all happen,” he says. Their efforts paid off: Shaunak Sen’s All That Breathes became the first Indian film to win the Grand Jury Award.

All That Breathes is what is often called a “sleeper hit,” with its renown mainly through word of mouth.

The creative process

As a filmmaker, Shaunak’s process begins with being drawn to a broader conceptual idea, whether it’s sleep or the human-animal relationship. “Then, I start looking for people whose lives embody that idea,” Shaunak explains. “The specificity of their lives takes on the impact of blunt force – these are the tools I use. My style is observational, controlled and aesthetised, especially in comparison with the handheld, gritty feel of Cities of Sleep.” His work is a juxtaposition of fictional storytelling in service of the documentary world. “It’s what I want to do in the future as well – marry these two styles. Even a documentary should have that lyrical, poetic flow.”

The film comes with an important social message but Shaunak shies away from taking what could be conceived as an overly preaching tone. “If you look at anything long enough, whether it’s the homeless people or two brothers rescuing birds, it starts registering itself on every level – social, emotional and political,” he says, adding, “I don’t take an overt social approach, it sort of seeps in on its own.”

Optimistic future

He’s already on the hunt for his next project, “reading a lot and examining vague themes at the moment.” And there’s room for exploration. India is a good place to be for a documentary filmmaker, gone are the days of scrambling for funds and catering to niche audiences. “The toolkit of cinematic language was greatly limited,” Shaunak remarks. A steady rise is evident, though, with Deepti Kakkar and Fahad Mustafa’s Katiyabaaz (Powerless), Vinod Shukla’s An Insignificant Man, the 2021 documentary A Night of Knowing Nothing directed by Payal Kapadia and Shaunak’s own work, all winning prizes on international platforms.

- Follow Shaunak on Instagram