(August 18, 2021) Realism and socio-political commentary—this is what makes Mira Nair‘s art exceptional. With heavy influences of Indian roots at the center of her storytelling, the 63-year-old’s work is brushed with real cultural elements. It’s the authenticity of representation that colors her films and make them a spectacle to watch. The filmmaker is a pro at conveying universal emotion with her craft, and it’s this sentiment that connects her to millions across the globe.

In the last few decades, Nair has become a force to reckon with in world cinema. With films like Salaam Bombay, Namesake, Queen of Katwe and A Suitable Boy in her repertoire, Nair has proven that Hollywood can be won over with Indian content.

Here’s the story of the woman who made it big in the world of cinema.

Rourkela to Harvard

Born in a Punjabi family in Rourkela, Orissa to a diplomat father and a social worker mother, Nair was introduced to poems of Faiz Ahmed Faiz and ghazals of Iqbal Bano, Noor Jehan and Begum Akhtar at an early age, thanks to her dad who was raised in Lahore. But it was English Literature that caught her fancy when she moved to Shimla to attend Loreto Convent at the age of 13. She graduated in Sociology from Miranda College in Delhi and it was here that she fell in love with theatre. The set, the performances and the art of bringing stories alive on the stage blew Mira’s mind. With dreams of studying drama, a 19-year-old Nair found herself accepted to Harvard University on a full scholarship.

Mira Nair is one the most celebrated filmmakers

Harvard was a turning point in Nair’s life as it opened her to new ideas and perspectives. It was a training ground for the filmmaker in the making. Though the drama course fell flat, Nair enrolled in a still photography course that taught her to capture the world within a frame. Ecstatic to learn a new way of looking at things, it was direction that gradually attracted Nair for its collaborative nature.

However, it wasn’t commercial cinema that she was interested in. She was keen to tell real stories of real people. It was realism that became a part of Nair’s initial documentary experience, and that gave birth to her first documentary So Far From India, a 52-minute story of an Indian newspaper dealer living in the subways of New York. Nair’s way of storytelling wasn’t just impressive but gripping too. Her debut won big at the American Film Festival and New York’s Global Village Film Festival. Her next project India Cabaret about the exploitation of female strippers in Bombay was yet another example of her exemplary filmmaking skills.

The film that took Mira to the Oscars

It was in 1988 that Nair transitioned into narrative filmmaking with Salaam Bombay, a crime drama about Mumbai’s street children. With no funding or proper actors, Nair spent many sleepless nights to bring together this film. For someone who believed in her story so much, she kept up with realistic cinema and chose actual street kids to act in her film.

The film catapulted Nair to international fame as Salaam Bombay won 23 awards including the Camera D’or and Prix du Public at the Cannes Film Festival. Not only this, Nair took an Indian film to the Oscars, 30 years after Mother India. Salaam Bombay was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, making it the second Indian film to achieve that feat.

When Hollywood beckoned

Salaam Bombay opened doors for international collaborations which gave way to her 1991 film Mississippi Masala starring Denzel Washington. Like Salaam Bombay, this film too received a great response from critics and won three awards at the Venice Film Festival. In 2001, it was a homecoming of sorts for Nair when she directed Monsoon Wedding, a film about Punjabi Indian weddings. But it wasn’t just a film that had song, dance and a wedding at its center: Nair touched upon child sexual abuse and its fallouts. The film grossed $30 million worldwide and was awarded the Golden Lion award at the Venice Film Festival, making Nair the first female recipient of the award.

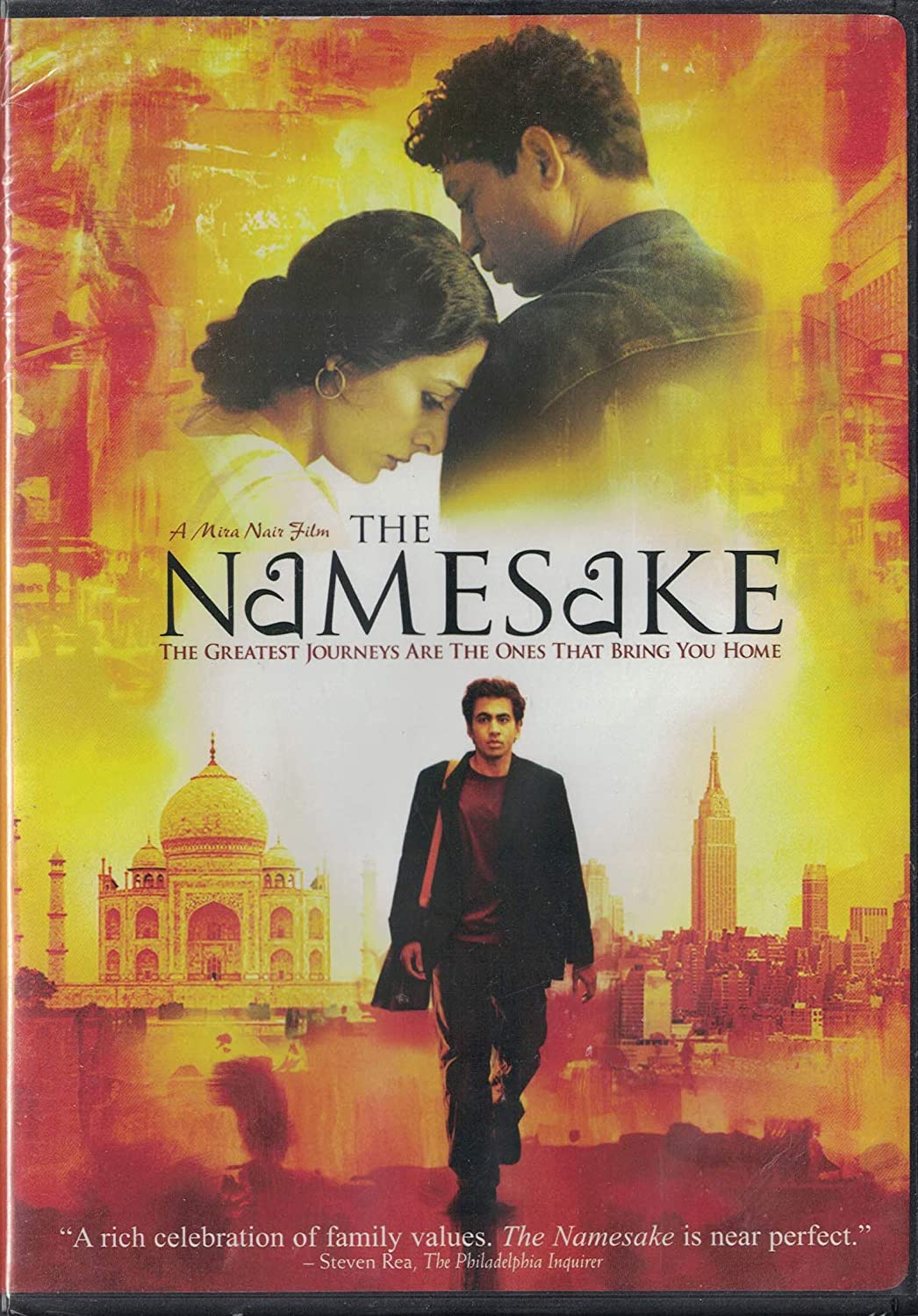

In the following years, Nair moved from strength-to-strength with films like Hysterical Blindness and Vanity Fair. The filmmaker had become a name to reckon with in the cinema circles so much so that she was offered to direct Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix. However, she turned it down for the big screen adaptation of Jhumpa Lahiri‘s 2003 bestseller Namesake.

Lahiri’s Namesake spoke to Nair like nothing else, especially at a time when she was mourning the loss of a family member. The book comforted her and Nair knew that this story needed to come out in a big way.

The poster of Mira Nair’s 2006 film Namesake

In a conversation with Entertainment Weekly, she said,

“This book sort of hit me like a bolt of lightning. In February 2005, my mother-in-law died [because of] malpractice in a New York hospital, and we buried her absolutely not prepared to lose her. I read [The Namesake] completely in a state of mourning, and I felt a shock of recognition that Jhumpa Lahiri understood exactly what I was going through. It was like a fever. I had two films I was supposed to make but I just dropped everything, and nine months after reading the book I was shooting the movie.”

A filmmaker with compelling stories

In 2012, Nair returned to the big screen with The Reluctant Fundamentalist after the initial hiccup of struggling to find financiers for five years for a film that addresses some deep social issues. Based on Mohsin Hamid‘s book, Nair’s film is a poignant story of a Pakistani man whose life changes in America after the 9/11 attacks.

Nair has her roots in Pakistan as her father was raised in Lahore before moving to India before Partition. She grew up on songs and stories from our neighboring country. Her first visit to Pakistan became an inspiration to make the film.

“As an Indian director, we usually only tell tales of the Partition. We don’t know beyond that. So, it was my springboard to wanting to do that. Then I read the book, about 18 months after my trip [to Pakistan], and it just possessed me. Not only was it that opportunity to speak about modern-day Pakistan, it was also a dialogue with America, which I really think we desperately need because we have only had a monologue from here, so far, about the other parts of the world that we impact with foreign policy, and guns. Also, I feel it’s about time we go beyond that “us” and “them” approach and go into the more complicated layers that we all live with. Like we say in the movie, we are more than these things. Mohsin and me have lived in these two cultures specifically for half our lives—there’s a place from which you embrace that multiplicity and you want to use what you’ve learned in what you make,” she told Interview Magazine.

The film won many international awards. Nair, too, picked up the German Film Award for Peace for The Reluctant Fundamentalist for inspiring tolerance and humanitarianism.

Four years after the success of The Reluctant Fundamentalist, Nair set her next film in Uganda. Being married to Indo-Ugandan political scientist Mahmood Mamdani, whom she met during the shooting of Mississippi Masala, Nair found the setting for Queen of Katwe in a slum of Kampala that was home to a chess prodigy. The filmmaker collaborated with the Oscar-winning actress Lupita Nyong’o for this beautiful biographical drama.

In 2020, Nair brought alive Vikram Seth‘s A Suitable Boy on Netflix and transported the world to an India that was questioning love, national identity and religion in an attempt to find its own way after liberation from the British Rule. It was Seth’s idea of idealism and romance in Nehruvian India that attracted Nair to the book.

With each of her films, Nair puts a part of her soul on display. Her body of work is a window to the world that’s often lost. Her stories are influenced by her Indian roots and delicately brushed with real cultural elements, and it’s this perfect blend that makes Nair’s work exemplary.

Giving back

While the filmmaker divides her time between Uganda and America, it’s India where her heart lies. It was during the shooting of Salaam Bombay that Nair realized Mumbai’s street kids were exposed to a lot without having any guardian in the form of an organization that could look after them. This gave birth to the Salaam Baalak Trust in 1988, an NGO that provides support for street children. Interestingly, Nair used the proceeds from her Oscar-nominated film to establish Salaam Baalak Trust. In the last three decades, the trust has provided support to 112718 children and given 1421 jobs.

Nair’s 1991 film Mississippi Masala took her to Uganda and that’s where she fell in love with the stories and talent of East Africa. She realized that authentic stories of Africa were not being immortalized due to lack of proper training. In order to bridge the gap, Maisha Film Lab was born in 2004 to support the careers of East African filmmakers with mentorship programs and courses.

Nair is a filmmaker with a difference and her philosophy of standing out reflects in each of her works. Be it her outstanding films that speak volumes about the authenticity of representation or the universal emotions, Nair has put herself in the league of some of the best filmmakers in the world.