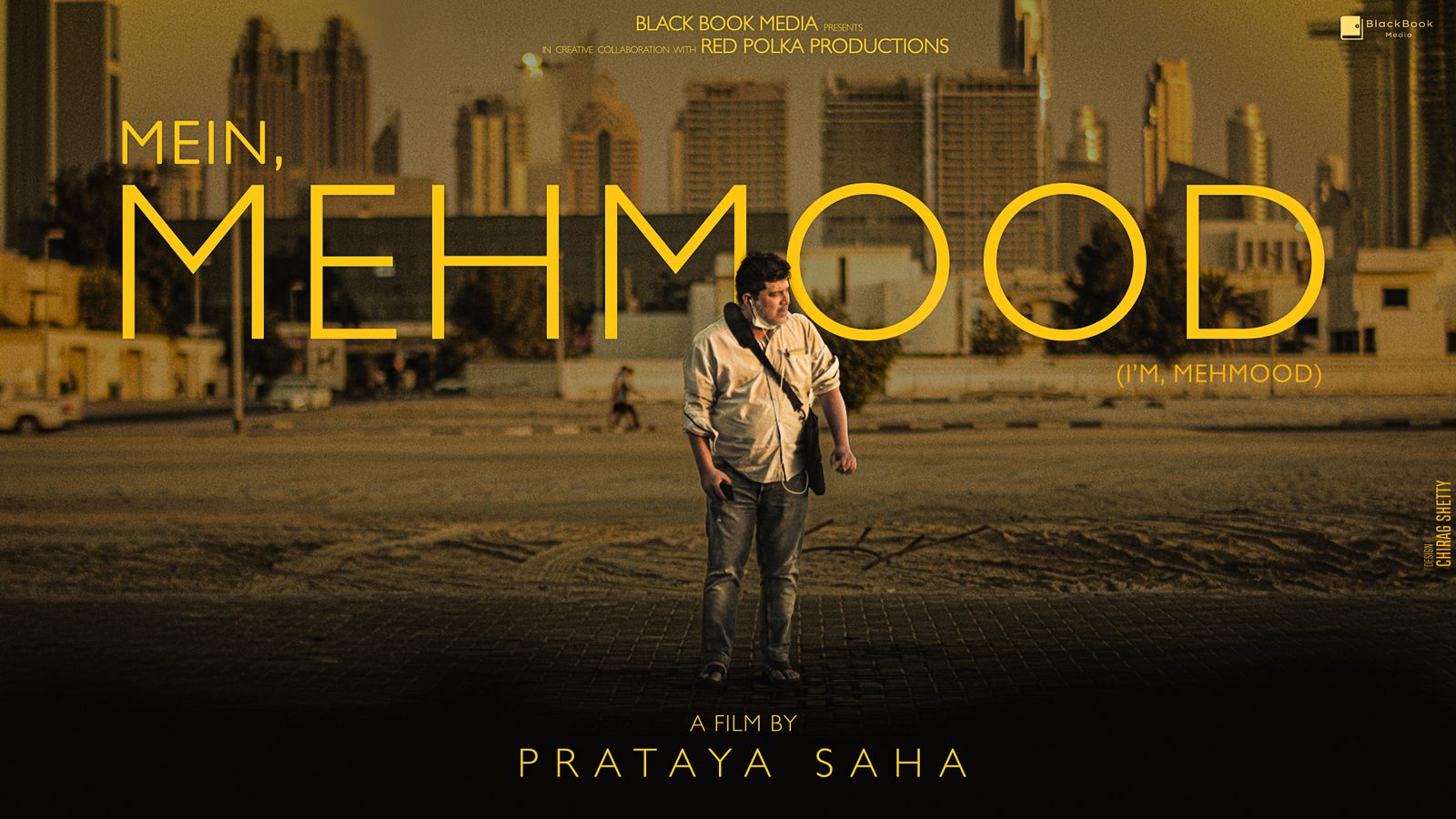

(July 26, 2022) “Sir, it’s time to go, we’re closing.” Filmmaker Prataya Saha was snapped out of his reverie by an impatient janitor waiting to close the cafe at which he sat in Sharjah. Saha picked up his things, smiling – his job was nearly done. He called Ozair, an acquaintance from Bengaluru, who would also go on to star in the film. Their paths happened to cross in the UAE, where Prataya had been to shoot a music video for a UK label. “He asked me, ‘why don’t we do something here?’ I had a flight out in two days but Ozair had promised to help get my visa extended if I could produce a script he liked,” Prataya tells me, as he catches up with Global Indian on a rainy Saturday afternoon in July, one year later. As it happened, Ozair loved what he saw and Mein, Mehmood was born, in ten intense hours spent huddled with pen and paper at a Costa Coffee. Shot entirely in Dubai in 2021, Mein, Mehmood will premiere at the IFFSA in Toronto, North America’s largest South Asian film festival, on August 15, 2022.

Filmmaker Prataya Saha

In August 2021, Just Another Day, Prataya’s short film on abuse during pregnancy, was the only Indian entry at the prestigious New York Asian Film Festival, where it premiered in August, 2021. “It’s the same festival at which Dil Se premiered in 1998,” he says. “One in six women die of abuse caused during pregnancy,” he explains, “but the matter is rarely talked about.” Just Another Day also won an award from Kuthaya Dumlupinar University, Turkey, on the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women. Mein, Mehmood deals with a less formidable subject but has its share of pathos too – it is the story of the lonely lives of (mostly blue-collar) immigrants in Dubai, who live cocooned against the world around them because they do not speak the dominant global language – English.

A reality that made to the 70mm

In 2017, Prataya founded Red Polka Productions, leaving behind his life as a statistical analyst to devote himself to art full time. The company made its debut The Good Wife, a raw, yet poignant take on the restricted lives of women, starring his co-founder, Anshulika Kapoor. Saha is well known today for his music videos, which have dominated the mainstream – Oye Hoye, for instance, has garnered some 14 million views since its release for T- Series. Kashish, also made for the same label, has around five million views across mainstream media platforms. It’s a big leap, admittedly, from artsy cinema to pop music videos but the filmmaker says that both call for creativity in their own way. “Whether it’s a short film or a music video, you start with ‘action’ and you end with ‘cut’,” he laughs.

Prataya recalls, the languorous evenings of his childhood in Calcutta, spent sitting out on the balcony. As an only child, Prataya was accustomed to solitude and developed then, the art of observation. That keen eye lends itself to his journey as a filmmaker and as a writer.

A still from Red Polka Productions’ The Good Wife

Poetic though his films might be, Prataya accepts that real life is far more prosaic – the belief that led him to the stability of corporate life. He began his career as a statistical analyst and it was through work that he first went to the Middle East in 2013. There, he used public transport every day, packed into train compartments with immigrants from Sri Lanka, India, Afghanistan and Bangladesh. He noticed, that they “wouldn’t make eye contact, or talk to you. Initially, it seemed rude.” As he began to mingle more with them, he realised that language was a big barrier.

“One can argue that it’s just a medium of communication but the fact is that we judge people for not being able to speak in a certain tongue. It gives rise to a lot of societal divides,” Prataya remarks. It reminded him of those evenings on his balcony, watching life go by. He noticed, even then, a stark difference between those who spoke English and those who did not – the latter seemed to suffer from a lack of confidence.

In the Middle East, he found this more than ever, to still be true. Some years later, he made the same observation in London, where “immigrants from other parts of Europe, like Poland, who also came across as standoffish, for not being able to speak English. And I could sense the emotions being bottled up inside them.” Fluent in Bengali, his native tongue, he would watch the faces of Bangladeshi cab drivers light up as they recognised the language of their homes. And his smattering of Urdu and Hindi was enough to delight the Pashto-speakers from Afghanistan.

So, when he sat down to write Mein, Mehmood, the story was already there, waiting to be told. He had researched the subject, which threw up some interesting revelations. “People who don’t know English are less likely to receive healthcare,” he says, surprisingly. “I spoke to immigrants in the Middle East who told me their stories. There are lots of factors that stop people from leading a certain kind of life but how justifiable is it that one language can have such a drastic impact on so many people around the world?

Mein, Mehmood

When passion came calling

When work took him to London in 2015, he saw people from different nationalities, living across the socio-economic spectrum. Walking through the streets he would encounter musicians busking, “drumming on utensils on the street. They were sitting in the cold but they looked so happy.” It made him wonder about his own life – he had always loved photography and writing but life had brought him to a place that was totally disconnected from his passions. He decided then, that he would quit his job.

His time in London was as an incubation period for his dream of being a filmmaker and starting his own production house. He returned at the start of 2016, complete with a two-year plan. “I knew I was going to quit but I had nothing to fall back on, having just invested in a house in Bengaluru.” The next two years were spent trimming down every arbitrary expense. If something at a clothing store caught his eye, he would think, “This money could get me a new filter.” When he thought about upgrading his car, he thought, “This could get me a new Sony camera. I even ended up cutting down my social circles because there were no more nights out, no expensive restaurant meals.”

During the two-hour cab ride home from work, he would “listen to Chinese instrumental music to calm down” and the minute he arrived, he would get cracking on his creative pursuits. “And during the day, my job involved Maths. I felt like I was leading a split life. It was a struggle but I did it meticulously, every day for two years.”

A still from Mein, Mehmood

In 2018, he launched himself full-time as a filmmaker and Red Polka Productions came to be. Their debut production, The Good Wife (2020) is still doing well on OTT platforms. “Even now, I get messages from people who have seen the film on Disney Hotstar and are writing to me about it,” he smiles. “It was great to collaborate with someone like Anshulika, who is so well known in the circles.” The story centres around a woman who lives by herself in a sprawling old home in Calcutta, and when the film starts, is setting out to buy fish in anticipation of her husband’s return home. It’s a “slice of life film,” as Prataya puts it, a style he has come to make his own.

Taking the next step in his journey as a filmmaker, Prataya is working on his first regional short film with actor Deboprasad Halder. The Golden Cage stars Anshulika Kapoor and House of Three designer Sounak Sen Bharat and is set in Calcutta in 1989. “I want to take in as much as I can, learn as many forms of filmmaking as possible. I tell myself that I started off a little late and it makes me feel like a man on a mission. There’s so much to learn.”

- Follow Prataya on Instagram