(March 1, 2024) Racism and racial hate crimes have been major issues being faced by minorities around the world. Fortunately, there are individuals like US-based activist Manjusha Kulkarni, who are determined to use their experience, influence, and positions to help make the world a more inclusive place. The activist, who cofounded Stop AAPI Hate four years ago, has been awarded the prestigious James Irvine Foundation award for confronting hate and discrimination against AAPI (Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders) communities with data, partnerships, and policy solutions. She was also acknowledged as Time’s “100 Most Influential” People in 2021 and won the Racial Equality Award in 2022.

“It’s incredibly humbling. There are so many people who have been involved in the effort. I want to acknowledge those people who are doing this work, day in and out, without much pay or prestige. This is now a movement. Even the monolingual grandparents came out to say we are not going to take this. There is a lot of work to be done to know and understand what is happening in our communities, and then bring about belonging for significant populations,” expressed the activist, who currently serves as the Executive Director at the Asian Pacific Policy and Planning Council, a coalition of organisations working for the rights of the oppressed.

From humble beginnings

At the age of two, Manjusha and her parents, both physicians in Alabama, migrated from India. During her teenage years, she witnessed her mother successfully lead a class action lawsuit against the state, challenging discriminatory policies targeting non-European doctors. “My interest in public welfare and civil rights began in 1971, when my parents immigrated to the USA. Before the Immigration Act of 1965, non-Europeans were not allowed to immigrate to the U.S. The Act removed racial barriers to immigration and opened specific pathways; only professional visas were granted. My parents came here as physicians. My father joined a practice in Alabama, but my mother was denied a job when she applied at a local hospital,” shared the activist.

She further added, “During an interview, a panel of white male physicians said to her, “Why do you foreigners come to the United States and take all of our jobs?” My parents hired an attorney, and it became a Class Action Lawsuit. I was in fifth or sixth grade, hearing words like class action lawsuit! Seeing the courage it took my parents to bring a lawsuit against my dad’s colleagues and seeing that the law could provide redress made me change my plan of following in my parent’s footsteps to become a doctor.”

ALSO READ | Ambassador Geeta Rao Gupta’s journey is empowering millions

This pivotal experience, combined with instances of feeling marginalised as one of the few AAPI students in her school, sowed the seeds of Kulkarni’s activism. It motivated her to pursue a law degree and a career dedicated to civil rights. “Seeing that the law was a vehicle for change and actually able to redress the wrongs that my parents experienced was really motivational for me,” the Global Indian shared during an interview.

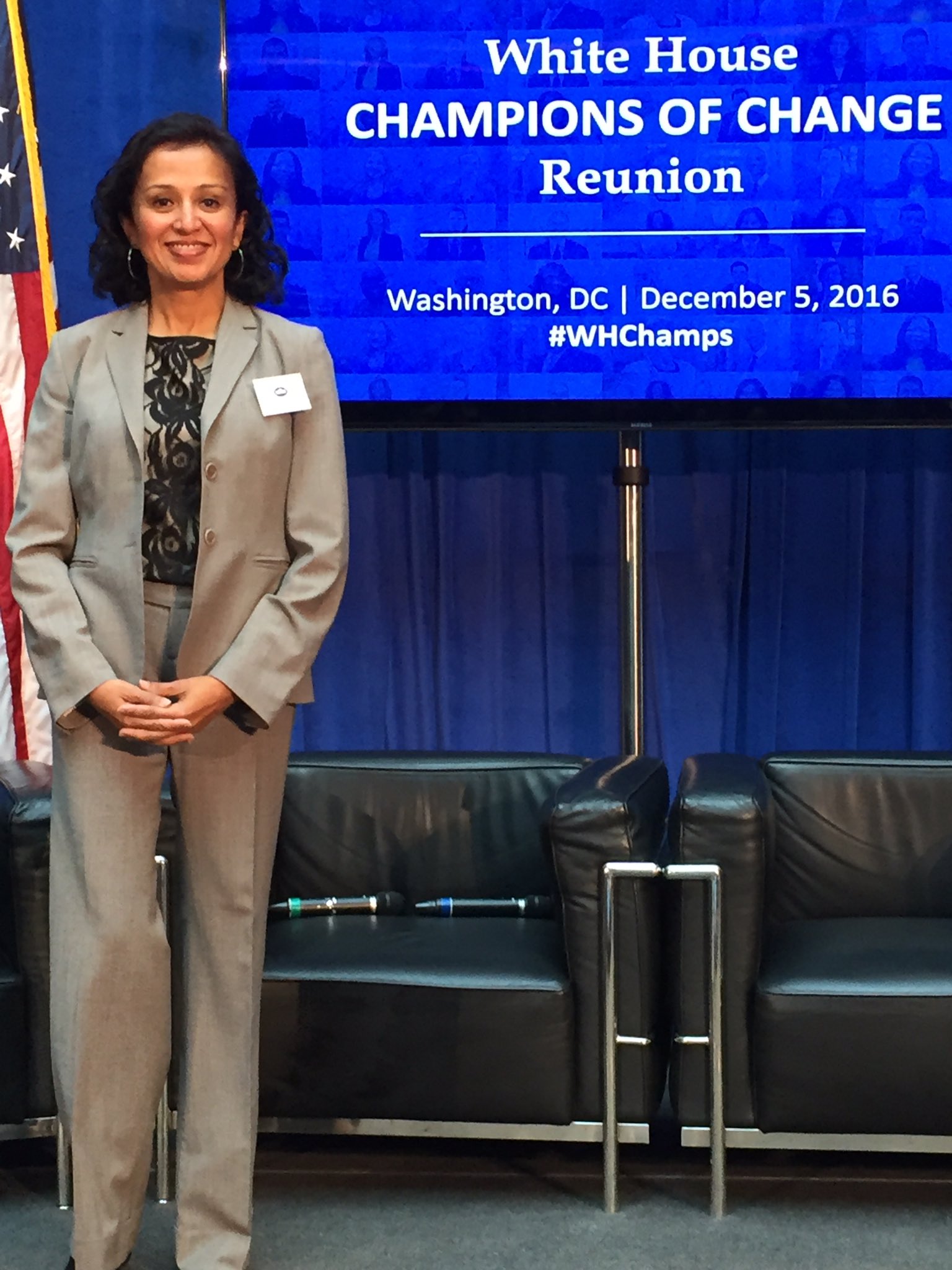

Following completing a JD at the School of Law, where she pursued her undergraduate studies at Duke and gained valuable experience during a gap year at the Southern Poverty Law Center, Kulkarni has forged a career in antidiscrimination law and advocacy. The activist also served as an attorney for the National Health Law Program and later took on the role of executive director at the support services nonprofit South Asian Network (SAN). Her efforts at SAN led to her receiving a Champions of Change award from the Obama administration, recognising the organisation’s impactful work in educating Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI) about the Affordable Care Act.

Advocating for justice

In 2017, Manjush assumed the leadership of the AAPI Equity Alliance. The activist successfully transitioned the forty-year-old organization into a new era, transforming it from a behind-the-scenes entity to a pioneering force in healthcare access, interpersonal violence, and mental health initiatives. Talking about the organisation’s measures to solve the hate crime, the activist said, “We’ve been focused for many years, if not decades, on ensuring a robust AAPI vote and representation. You can’t solve what you don’t measure, so with the census, we wanted to ensure a robust count — to know where our communities are, who they are — and with that data, to help ensure that they have a voice in our political system.”

An unfortunate incident that took place in LA, propelled Manjusha to establish Stop AAPI Hate in 2020 – together with Chinese for Affirmative Action co-executive director Cynthia Choi and San Francisco State University Asian American Studies Department professor Russell Jeung.

ALSO READ | Priti Krishtel: Indian-American lawyer is fighting against racism in healthcare

“In 2018, in LA, an Asian American middle school child was attacked in the schoolyard before there was a single confirmed case of Covid-19 in southern California. “You are a Covid carrier, go back to China,” he was told. He said, “I am not Chinese.” Not to distance himself, but to say I am not from there, I have nowhere to go back to. The other kid punched him in the face and head 20 times. We helped the family cope and held a press conference with local leaders. That press conference got quite a bit of coverage. My colleagues saw the same thing in the Bay Area. Within two weeks we noted several hundred incident reports from across the country. We collected data with the intention of releasing it to the public and lawmakers, and got close to 700 incident reports with minimal public outreach,” said the activist.

As an attorney, Manjusha has always been determined to use her skills to stop racism. “I have a lot more to do in this space. I’m not necessarily in the business of changing hearts and minds; I want to change policies to change behaviour,” the activist said, adding, “One thing that we make clear at Stop AAPI Hate is that it’s not just about interpersonal violence or hate, but the institutional and structural mechanisms that make racism possible.”

Read a similar story of Eboo Patel, turning diversity in America.