(April 14, 2025) In the crowded chawls of Bombay in the early 1900s, a young boy could often be found hunched over borrowed books, lost in the world of ideas while the city roared around him. His name was Bhimrao Ambedkar or BR Ambedkar, and he belonged to a caste considered “untouchable” — his mere presence could trigger a thousand social snubs. But this boy, born in 1891 in a military cantonment town called Mhow, wasn’t going to be written off. He would grow up to become not just the chief architect of the Indian Constitution, but one of the first true Global Indians — someone who went abroad to learn, and returned home to build a new nation.

On his 134th birth anniversary, Ambedkar is remembered as a scholar, reformer, and nation builder — someone who returned to India not just with degrees, but with a vision to rewrite its future.

A Dalit Boy, a Bombay School, and a Dream That Defied Caste

Bhimrao was the youngest of 14 children in a Mahar family. His father, a Subedar in the British Indian Army, believed in the power of education. But belief didn’t stop discrimination. In school, Ambedkar sat on the floor, far from other students. He wasn’t allowed to touch the water pot. Teachers often ignored him altogether.

The family moved to Bombay when Ambedkar was a teenager. There, he enrolled at Elphinstone High School — the first Dalit student to do so. When he passed his matriculation exam, his community celebrated like it was a wedding. Education, for them, wasn’t just success — it was survival.

In 1912, he completed his degree in economics and political science from the University of Bombay. The real turning point came a year later, when he received a scholarship from the Maharaja of Baroda to study abroad.

First Dalit at Columbia, First Indian with a Foreign PhD in Economics

Ambedkar boarded a ship to America in 1913, bound for Columbia University in New York. He was one of the first Indians — and the first Dalit — to study there. For the first time in his life, he was seen not as a caste, but as a student.

“My five years of staying in Europe and America had completely wiped out of my mind any consciousness that I was an untouchable,” he later wrote, “and that an untouchable wherever he went in India was a problem to himself and to others.”

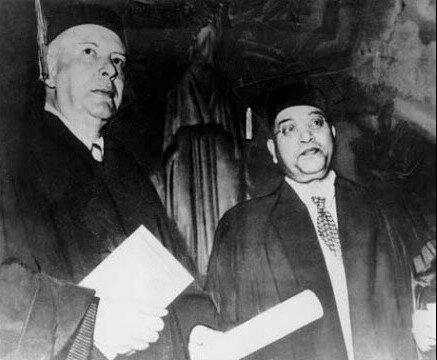

BR Ambedkar at Columbia University

At Columbia, he earned his MA in 1915. He wrote his first thesis on caste in India, laying the groundwork for his lifelong fight against inequality. He would go on to become the first Indian to receive a PhD in Economics from a foreign university — a milestone that was as historic as it was personal.

Then came London, where he studied at the London School of Economics and trained in law at Gray’s Inn. Despite running out of money and returning to India mid-way, he completed his D.Sc. in Economics from LSE in 1923 — a rare achievement even today — and later earned his PhD from Columbia in 1927. By the time he returned home, Ambedkar had academic credentials that few in India could match.

How Ambedkar Turned Discrimination into a Movement

Despite his global education, Ambedkar was still seen as “untouchable.” In Baroda, where he worked briefly for the state government, nobody would rent him a room. Clerks refused to hand him files. Disheartened, he resigned and returned to Bombay to practice law. But Ambedkar wasn’t just looking to build a career — he was preparing for a fight.

In 1924, he founded the Bahishkrit Hitakarini Sabha, to promote education and social reform among Dalits. He also launched a Marathi newspaper, Mooknayak (Leader of the Voiceless), to raise awareness around caste injustice.

Ambedkar’s Rise as a Political Force

Ambedkar quickly became a voice to reckon with. In 1927, he led the Mahad Satyagraha, a protest to demand Dalits’ right to access public water sources. When orthodox leaders pushed back, he led a symbolic burning of the Manusmriti — a religious text that upheld caste hierarchy.

Throughout the 1930s, he campaigned for political representation of Dalits. In the lead-up to elections under British rule, he argued for separate electorates for Dalits. Gandhi opposed the idea, worried it would divide Hindus. The compromise came in the form of the Poona Pact of 1932 — which gave Dalits reserved seats in legislatures without creating separate electorates.

BR Ambedkar later formed the Scheduled Castes Federation, a political party focused on uplifting the marginalised.

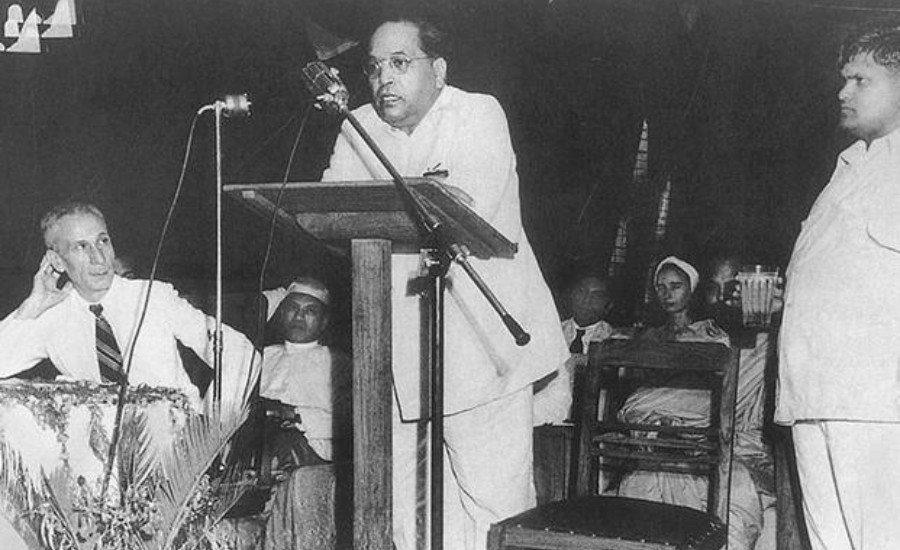

Not just a lawmaker — a nation builder

When India became independent in 1947, Ambedkar was invited to join the first Cabinet. While most remember him as the Chairman of the Constitution Drafting Committee, fewer know that he also served as India’s first Labour Minister.

In that role, he made one of the most lasting changes to working-class life in India: reducing the industrial workday from 14 hours to 8. This brought India in line with global labour standards and protected countless workers from exploitation. He introduced maternity leave, medical benefits, and employee insurance schemes long before they became common rights.

But his biggest legacy remains the Constitution — a document that not only gave India its democratic foundation, but also legally abolished untouchability, prohibited discrimination, and laid out affirmative action for the marginalised. His legal writing made caste discrimination punishable by law — a powerful move in a society that had tolerated it for centuries.

His fight against the caste system was never just political — it was deeply personal. He understood, more than anyone else in power at the time, how social reform was essential for national unity. “So long as you do not achieve social liberty, whatever freedom is provided by the law is of no avail to you,” he once said.

BR Ambedkar didn’t just build legal frameworks — he built the vision for an India where identity didn’t determine destiny. And he knew education was the key.

Turning to Buddhism

In his final years, Ambedkar grew convinced that Hinduism could not be separated from caste. After deep study, he found an answer in Buddhism — a path of equality, reason, and compassion.

On October 14, 1956, he converted to Buddhism in Nagpur, along with his wife and over 500,000 followers — one of the largest mass religious conversions in history. For many Dalits, it marked a break from centuries of oppression. Ambedkar passed away weeks later, on December 6, 1956, in Delhi. He was 65.

A Legacy That Won’t Fade

Ambedkar’s influence didn’t fade with his death — it only grew stronger. In 1990, he was awarded the Bharat Ratna, India’s highest civilian award. His writings are taught in universities, his speeches quoted by activists and lawmakers alike.

Most importantly, his work lives on in India’s legal and social structures. Today, over 200 million Scheduled Caste citizens benefit from reservation policies and constitutional protections — a direct result of the groundwork he laid for inclusion and equality.

He once said, “Cultivation of mind should be the ultimate aim of human existence.”

Ambedkar lived that truth. From a child denied water at school to the man who gave India its most powerful legal document, his story is a reminder that one person — with education, courage, and clarity — can reshape a nation.

ALSO READ | Noor Inayat Khan: The Indian woman who became Britain’s spy princess in WWII