(February 11, 2023) Recently, I began reading Ilango Adigal’s third-century Tamil classics, Shilapaddikaram and its sequel, Manimekalai. The man behind the exquisite translation is Alain Daniélou , a name I had heard before but hadn’t really noticed. Still, the depth and beauty of the writing made me wonder. Why was a Frenchman translating Tamil epics? Was he another remnant of Tamil Nadu’s colonial past? An Aurovillian, maybe? He was neither. Pulling at the thread led me on a journey into a life that he himself describes as ‘labyrinthine’, beginning with his birth into Norman nobility and Roman Catholicism that led him, from the avant-garde circles of Paris to Banaras. Global Indian takes a look at the maverick genius who took Hindu philosophy, music and architecture to Paris, New York and the world.

Daniélou, who received the Sangeet Natak Akademi Fellowship, the highest honour bestowed by the institution, remains nearly unmatched as an Indologist and Musicologist. A dancer, he spent time in Paris, as an intellectual, he rubbed shoulders with the likes of George Steiner and Anthony Burgess and in India, with Rabindranath Tagore. Here, he studied music, Sanskrit, literature and Hindu philosophy at Banaras Hindu University and lived in Varanasi on the banks of the Ganges. He was an exponent of the veena, and translated the works of Swami Karpatri who initiated him into Shaivism. After his conversion, he took the name Shiva Sharan or ‘protected by Shiva.

Daniélou translated the Tirukkural, Shilapaddikaram and Manimekalai when was working at the Adyar Library and Research Centre in Madras and went on to join the French Institute of Pondicherry. His website is extensive, maintained by the Alain Daniélou Foundation but aside from that, there is very little literature available on the man (in English) from the media, aside from a 2017 documentary ‘Into the labyrinth’ and a beautifully written obituary by James Kirkup for The Independent.

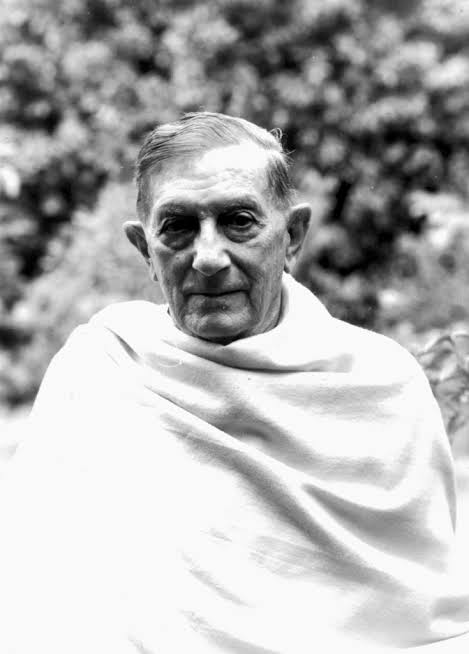

Alain Daniélou

Early life

“I was a sicky child,” he writes in his autobiography Les Chemins du Labyrinthe. “I was never sent to any of those noisy places called schools… for a boy without a future, this was considered a useless ordeal.” He was born into an aristocratic Norman family – his father was a “noted anticlerical and a minister in the Third Republic,” Kirkup writes, while his mother “was devout to the point of being called a fanatique.” She founded schools and the Order of Sainte-Marie, receiving the blessing of Pope Pius X for the latter.

Written off by doctors at an early age, Daniélou spent his early years in a “large, very uncomfortable stone house” bought by his father in Brittany. Daniélou would spend his time in the thick woods on the property, creating small sanctuaries that he “adorned with sacred objects, symbols of the forest gods.” Needless to say, this didn’t go down too well with his mother. He was baptized, according to custom, although it left him “sad and indifferent.”

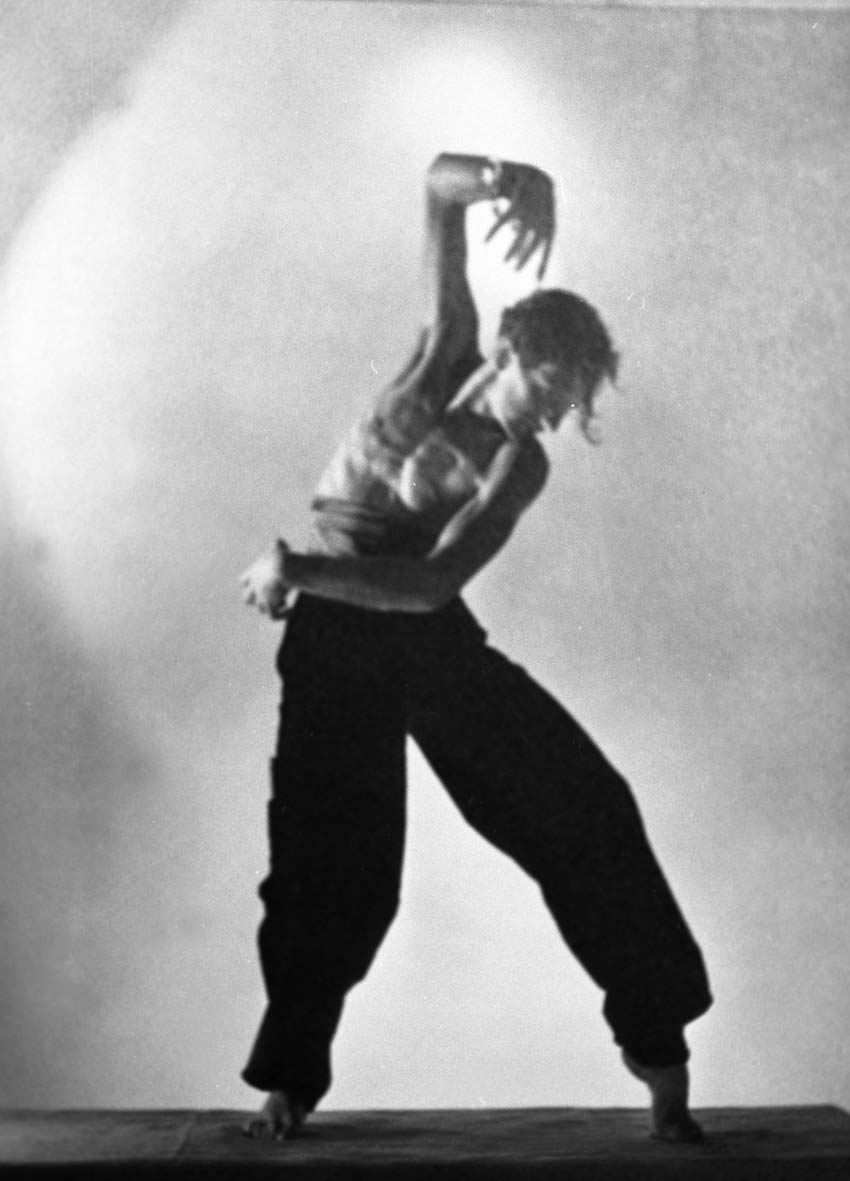

Daniélou did, however, learn piano and singing, encouraged by his father. He wrote poems, became fluent in English and practiced translation. At the time though, Daniélou loved to dance and went on to perform professionally. He had many friends in the ballet circles too, until, Kirkup writes, he “abandoned the dance for more serious matters.”

Photo: www.alaindanielou.org

Arrival in India

Daniélou had great wealth to his name and travelled extensively across Europe and Asia. Still, India held a special fascination. In the early 1930s, Daniélou ‘s partner was the Swiss photographer Raymond Burnier. The pair were fascinated by Indian art and culture and decided to go on an adventure. So, they left behind their Bohemian high life in Paris to make their way to Banaras.

They were among the first Westerners, it is believed, to see the now famous erotic sculptures in Khajuraho. Burnier took many photographs, which were featured featured in Paris in 1948 and a year later, in an exhibition at New York’s Metropolitan Museum. That took place in 1949 and Ajay Kamalakaran writes in Scroll.in, “a photo exhibition of medieval Indian sculptures was the talk of the town among New York’s intellectual elite.” Burnier even went on to become an Honorary Officer on Special Duty of the Archaeological Department of the government of India.

He had become more or less estranged from his family, apart from his older brother, Jean, who was kind to him. In the eyes of his family’s religion, he admits, he was a heretic. However, among the “Hinduists,” and with the Hindu religion, “which welcomed me among its members, there is nothing reprehensible about my style of life or my way of thinking.” In India, finally, the troubled young man had found a home.

Shantiniketan, Shaivism and a new life

In 1935, Daniélou enrolled at Benares University, where he would spend the next 15 years. He studied music, Sanskrit, Indian philosophy and Hinduism and remained in the University for the next 15 years, after being appointed research professor. He also began performing professionally on the veena.

Alain Danielou with his veena. Courtesy: https://www.alaindanielou.org

Danielou immersed himself in the Hindu culture and even took offence at what he perceived to be its dilution by foreign rulers and English-speaking Indians. He is a vocal critic, of Nehru and Gandhi and even of philosophers like “Vivekananda, Radhakrishnan, Aurobindo or Bhagwan Das.” He found instead, a scholar named Vijayanand Tripathi and would attend the discourses he led outside his house every evening. For many years, Danielou only read Hindi and Sanskrit. He also became a “strict vegetarian, observed all the customs and taboos,” he writes, and wore “the spotless, elegant and completely seamless dhoti and chhaddar.”

As Burnier was a great admirer of Rabindranath Tagore, Danielou accompanied him to Shantiniketan. Tagore went on to become one of Danielou’s greatest influences. Danielou even painted a portrait of the man. Tagore, on his part, was very impressed by the French scholar. ‘Tagore’s Songs of Destiny’ is still a part of The Danielou Collection.

He converted to Hinduism and adopted the name ‘Shiva Sharan’, which means protected by Lord Shiva. Les Quatre sons de la vie (translated as The Four Aims of Life in the Tradition of Ancient India), Le Betail des Dieux (1983), La Sculpture erotique hindou with photographs by Raymond Burier (1973) and La Musique de l’Inde du Nord (1985). His translation of the Kama Sutra, according to Kirkup, is “one of his great masterpieces.”

Journey to Madras

In Madras, Daniélou , now an accomplished Sanskrit scholar, decided to study Tamil. Working with local experts, he translated Ilango Adigal’s third-century epic romance, Shilappadikaram. It was also published in America under the title ‘The Ankle Bracelet. All this time, Daniélou was working at the Adyar but found “the puratanical atmosphere and the various taboos extremely difficult to bear.” In 1956, he ended his association with the library. Three years later, he went to Pondicherry and became a Member of the French Institute of Indology.

Controversy

Trouble followed Daniélou all his life, as he rebelled constantly against any puritanical form of thought. He even went up against Nehru and Gandhi, when the latter spoke out against eroticism in temple statues. Controversial or not, Daniélou ‘s contribution to Indian culture – and to the world – is immense. His books have been published in twelve countries, in several languages, from English to Japanese.

He returned to Europe in the last days of his life, living between Rome, Lausanne, Berlin and Paris. He died in Switzerland on January 27, 1994, leaving behind instructions for his remains to be cremated, according to Hindu tradition.