(February 6, 2023) As the viewer approaches The Bride’s Toilet, one of the best-known works by artist Amrita Sher-Gil, they are immediately struck by the intimacy of the scene. A young bride, resplendent in her wedding finery, sits before a mirror, surrounded by the trappings of her toilette. Her eyes are downcast, her expression thoughtful. In that moment, the viewer is transported to a private world, where the bride can reflect on the joys and challenges of her future as a married woman. As Sher-gil remarked, in a letter to a friend, “I want to paint the joy and sadness, the laughter and tears of people, to show the different aspects of life, and above all to be true to life.

“Sher-Gil’s paintings are marked by a powerful sense of empathy, as well as a keen eye for capturing the social and political realities of India in the early 20th century,” wrote Yashodhara Dalmia, Indian art historian and author of “Amrita Sher-Gil: The Passionate Life and Art of India’s Greatest Modernist”. Her bold approach to her craft and refusal to conform to traditional norms have earned her the nickname “India’s Frida Kahlo”. Global Indian takes a look at the iconic artist Amrita Sher-gil, who would have turned 110 on January 30, delved into themes of gender, class and sexuality, making her a true feminist icon who was far ahead of her time.

Amrita Sher-Gil. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Early life

Amrita Sher-Gil was born in 1913, in Budapest, Hungary, to a Punjabi Sikh father and a Hungarian-Jewish mother. Her parents were both accomplished individuals in their own right – father, Umrao Singh Sher-Gil, was a scholar and her mother, Marie Antoinette Gottesmann, was an trained opera singer. From a young age, Sher-Gil showed a talent for the arts, and began painting at the age of just five years old. In 1926, during a visit to Shimla, her uncle, the Indologist Ervin Baktay, visited Shimla and noticed the young girl’s artistic talent. She would paint the servants in her house, and get them to model for her, capturing their dignified and expressive faces in her drawings.

Art historian Yashodhara Dalmia writes, in her biography, Amrita Sher-Gil: A Life, “From the very start, her interest was in capturing people and the social milieu they inhabited.” Amrita’s early paintings were marked by a naturalistic style, a deep empathy for her subjects, and a remarkable sensitivity to their emotions.

Sher-Gil in Paris

In 1929, she enrolled at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, and discovered the European modernist masters like Paul Cézanne, Pablo Picasso, and Henri Matisse. It was here that she realized the immense potential of art to challenge and shape cultural norms. In a letter to her friend, she wrote, “I want to paint not just aesthetically but also socially. I want to do something for my country and its people.”

While in Paris, Amrita Sher-Gil continued to evolve as an artist. She painted several portraits of Parisians, capturing their refined elegance and bohemian spirit. She also painted landscapes, still life, and nudes, which showed her mastery of the human form and her deep understanding of light and color. An anecdote from Sher-Gil’s time in Paris illustrates her determination and commitment to her artistic vision. During a critique session at the École, her professor criticized her painting, stating that the figures in her work were not proportionate.

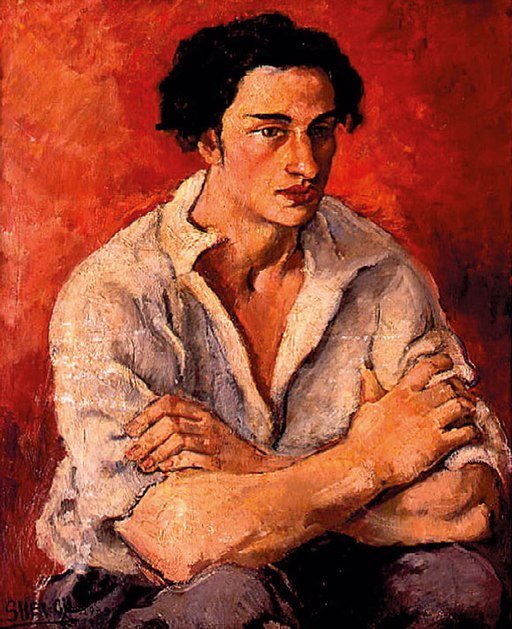

Portrait of Young Man, painted by Amrita Sher-Gil at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Sher-Gil’s response was simple but powerful: “I don’t paint people to please the academic eye, but to give voice to the emotions that stir within me.” She was also dissatisfied with the restraints of her upper-crust life, she ventured, as was fashionable at the time, into underbelly of Paris’ party circuit, into the small, often seedy cafes frequented by artists and bohemian intellectuals. “She was also very free in her relationships with men and there is more than one reference of her having been with women, too,” Dalmia told me in an interview. “She would stay out late and had a number of admirers.”

The return home

Amrita Sher-Gil returned to India in December of 1934, after studying in Paris for several years. Here, she found herself in the midst of a thriving art scene, where artists were exploring new techniques and styles, drawing inspiration from traditional Indian art forms as well as European modernism. One of the leading voices of the time was art historian and critic, B.N. Goswamy, who once said, “Amrita’s return to India marked the arrival of a new voice in Indian painting, one that would challenge prevailing norms and bring fresh perspectives to the table.”

In 1937, touring South India, she was greatly moved by the local women and depicted, in the bold colours inspired by the paintings in the Ajanta Caves, their pathos and their poverty. “I can only paint in India. Europe belongs to Picasso, Matisse, Brazque… India belongs only to me,” she wrote, in a letter to a friend. Her work went on to inspire, some years later, Rabindranath Tagore, Abanindranath Tagore and Jamini Roy, founders of the Bengal School of Art and also the Progressive Artist’s Group with artists like FN Souza, M.F. Husain and S.H. Raza. One of her most famous works from this time, Hill Women, is a testament to Amrita’s dedication to capturing the essence of Indian life. In this painting, she masterfully portrays the rugged beauty of rural women, working in the fields amidst a stunning backdrop of hills.

The Bride’s Toilet. Source: Wikimedia Commons

An unparalleled legacy

In 1934, Amrita held her first solo show in Bombay, which was a critical success. Her paintings, inspired by her travels and the people she met, such as Hill Women and South Indian Villagers Going to Market, brought a new perspective to the Indian art world, capturing the beauty and struggles of everyday life. “I believe that an artist has a social obligation and must use his art as a means of helping the suffering humanity, Amrita Sher-Gil wrote, again to Marie Louise Chassany.

She also produced The Bride’s Toilet, The Three Girls, and Young Girls, which became her most famous works. In an anecdote, historian R. Siva Kumar tells of how Amrita, who was always in search of new inspiration, would often travel to remote villages in India, seeking out new subjects to paint.

Sher-Gil died at 28, shrouded in mystery, days before the opening of her first major show in Lahore and Khushwant Singh writes of being among only a “handful of mourners” present at her cremation. Still, her work went on to influence modern Indian masters and the Indian government declared her paintings, most of which are housed at the National Gallery of Modern Art in Delhi, as national treasures.