(May 8, 2022) Over a billion people across the world live in slums – nearly one in six. Orangi Town in Karachi, Pakistan is by far the world’s largest, with some 2.4 million inhabitants. More than a million residents crowd together in Mumbai’s Dharavi slum, where development of low-income housing is overseen by the Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA). Over the years, thousands of people were moved out of temporary dwellings into brick and mortar shelters. It’s a step up, one would think. It’s not long before residents realise that their concrete tenements aren’t all they’re made out to be…

“Poor design causes a multitude of problems with regard to health, well-being and socio-economic interaction,” says Cambridge University’s assistant professor of sustainability in built environment – Dr Ronita Bardhan, in an interview with Global Indian. Sustainable, low-income housing is the architectural engineer’s area of work – she has spent years studying rehabilitation projects at IIT-Bombay, Stanford University and Cambridge University. Her aim: Attempting to provide data and tech-driven, culturally rooted design solutions that work both at the individual and community levels. While cutting edge technology is the need of the hour, Ronita believes firmly that it should consider the socio-cultural context within which it is being used.

However, faced with a problem of almost fantastic magnitude, authorities in slum rehabilitation projects around the world tend to rely on a purely quantitative approach. Working in isolation, without inputs from the health or energy ministries, the projects may fulfill the basic concern – shelter, but do little else.

Driven by data, transcending disciplines

Working out of the University of Cambridge, Ronita creates design solutions that marry engineering, AI and the social sciences. “Housing is not a noun, it’s a verb,” says Ronita. “It decides the way a person lives, their health, and their economic outcomes. Housing policies don’t cater to that, even though they should,” she adds. She’s currently working towards four UN Sustainable Development Goals – 3 (good-health and well-being), 7 (affordable and clean energy), 11 (sustainable cities and communities) and 13 (climate action).

Ronita’s approach is a call for demand-led design. Her approach is data-driven, “it brings a hard-core engineering model together with the social sciences.” Her work has taken her from India to projects in Indonesia, South Africa, Ethiopia and Brazil. She is the Director of Studies and Fellow in Architecture at Selwyn College. She also chairs the Equality Diversity Inclusivity Committee at the Department of Architecture and History of Arts.

Cry the beloved country

When she moved to Mumbai to join IIT-Bombay, she would often see sprawling apartment blocks whiz past her train window. She had no idea at the time why these buildings existed, apart from noting that they looked dense. These were the SRA’s tenement housing projects set, where Ronita would begin her research work.

The houses contained a range of shortcomings; from poor ventilation that resulted in indoor air pollution, the absence of natural sunlight that led to greater energy consumption through artificial lighting and the absence of space for women and children to gather outdoors. In one study, Ronita found that indoor pollution levels in SRA homes were five times over the global standards.

Design solution to reduce indoor air pollution

A data-driven approach requires far more than merely handing out questionnaires. Instead, Ronita and her team work to collect several hours of data, gathered through a series of informal chats and unstructured interviews, while simultaneously monitoring the built environment using a range of environmental sensors. In an effort to examine the conditions of 120 households in Mumbai’s chawls, “We stayed in the chawls, imitating the habits of the regular residents,” Ronita says. They placed sensors across the building to measure air quality, using the local mean age (LMA) of air as a parameter. They also considered the orientation and direction of the building, what surrounded it, area, thickness of the walls and the size of the windows.

“We want to develop strategies from these kinds of parameters,” says Ronita. By taking into consideration the economic, physical, emotional and interpersonal aspects of the individual’s life, the resulting design solution will help move away from the prevailing quantitative approach.

A rise in the incidents of tuberculosis in Mumbai’s rehabilitation projects led to further studies. They found the absence of sunlight allows the microbes to thrive, causing disease. It also led to increased energy consumption.

Gendered cities

In 2018, Ronita’s study, published in Habitat International – a Science Direct journal, found gender asymmetries in slum rehabilitation projects in Mumbai. Participants are made to feel at ease through a series of unstructured interviews and it was found that women were now largely confined indoors. Where activities like childcare were once a shared responsibility, the new projects had done away with open, community spaces where women traditionally gathered.

The SRA has done much work to bring people out of slum dwellings. However, “designing houses based on the current policy has knock off effects on health and energy,” Ronita explains. “There is no link between design and the actual lived experience. Houses are not just for shelter, they impact every part of our lives,” she says.

Data is gathered through a series of unstructured interviews and monitoring built environment through a range of sensors.

Poverty of time

Confined to their homes and burdened entirely with domestic duties, fewer women were going out to find work. The vast socio-economic networks maintained in the old slum dwellings no longer existed without socialising spaces. The green spaces invariably become illegal parking spots, places for hawkers, or even dumping grounds.

“The women would once go out every day to visit neighbours who lived 15 houses away. Now, although that neighbour lives three storeys above, they don’t meet for months. If women were spending 90 percent of their time indoors, they are now spending 99 percent,” Ronita explains. It is a poverty of time that in turn, leads to fiscal poverty as well.

The quantitative approach

A quantitative approach can easily sideline individual and local needs. “In South Africa, the level of poverty is a lot lower but the problems are more to do with things like drug abuse. You don’t find that in India, especially among the women,” says Ronita. Instead, when she interviewed women in SRA housing in Mumbai, she found they were thrilled to have toilets inside their homes and private indoor spaces. However, there’s still a lot to contend with for authorities and urban planners alike. Ronita is among those calling for demand-driven engineering solutions, with built environments catering to the needs of the individual. It involves trans-disciplinary collaborations to arrive at practical solutions.

A holistic approach and tweaked building by-laws can make a world of difference. “It can be scaled,” Ronita agrees. “Builders should not be granted free land until they comply with the by-laws. These need revision based on contextual factors and should never mention minimum thresholds for set-backs. When compliance is based on a minimum threshold, only the minimum provided. Let’s include elements like childcare facilities and socialising spaces within the legal framework,” she adds.

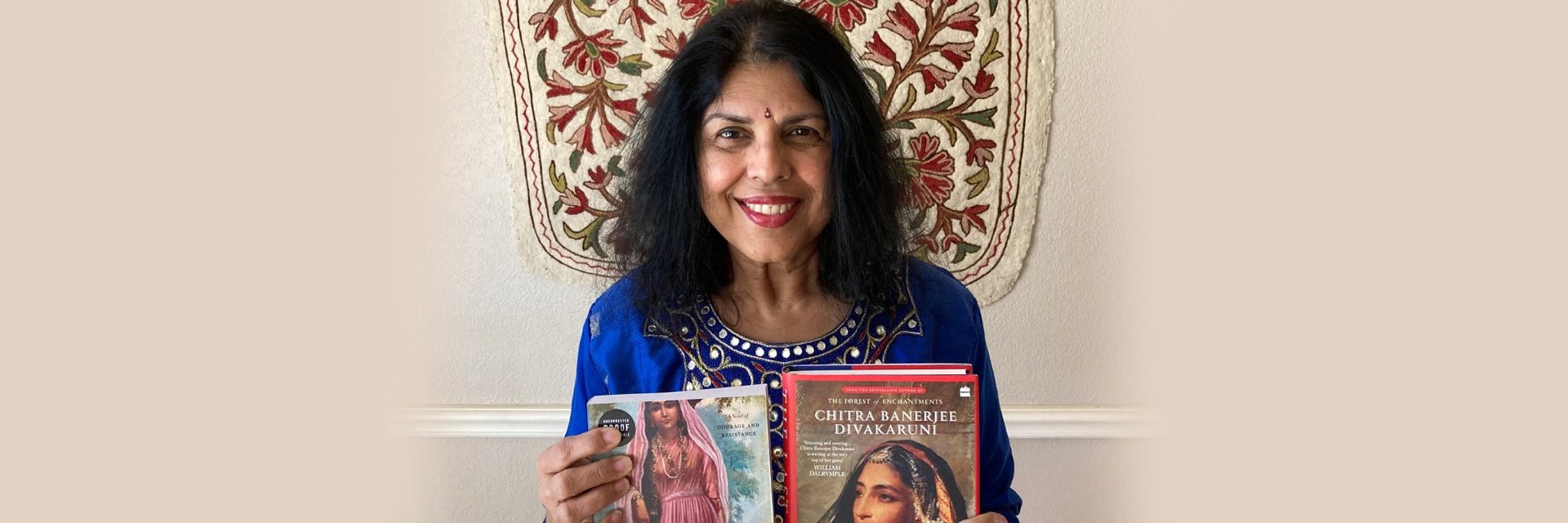

Ronita with women residents of Mumbai’s SRA housing

Efficient utilisation of space and energy

When she first began her work in the field, Ronita says cooling units inside people’s homes were a rarity. Today, most have more than one energy-intensive cooling devices. Bills have shot up and with inadequately designed homes, they’re only likely to increase further. “We assume that this demographic doesn’t really consume energy. That is a fallacy,” she says.

For all this, the efficient utilisation of space is paramount. Ronita recalls doing her doctorate at the University of Tokyo, and the 25 sq foot apartment she called home. “The tenements in Mumbai are actually larger but they feel very cramped. Not once during my time in Tokyo did, I feel like I needed more space. It’s all about design. I would wonder if it could be replicated but then, all technology should consider the socio-cultural context within which it is being used.”

Read a similar story of Jeenal Sawla, the Harvard grad reclaiming public spaces.