In 2016, when Alyia Krumbiegel stepped out of Kempegowda International Airport in Bengaluru, she did so into a blaze of cameras flashing and reporters firing questions at her. This was Alyia’s first ever visit to India and she “just wasn’t prepared for the media frenzy. It was astonishing,” she tells Global Indian. The first thing on her schedule was a trip to Lalbagh Botanical Gardens. She entered through the West Gate, originally known as ‘Krumbiegel Gate’ and thought, “Oh my God, I’m home. It was surreal. I felt this is where my life should be.”

Alyia’s story – and her great-grandfather’s obviously, is one of globalisation and multiculturalism that began far before these terms came into vogue. As India struggled under the British, a German man found home in Bengaluru, in a country that continues to love and treasure his legacy. During his lifetime, much of which he spent in India starting in 1893, he “landscaped his way,” according to Alyia, over 50 gardens, tea and coffee estates in the Nilgiris and across the South.

Alyia’s legacy from her great grandfather, goes back to the late 1890s, to her great-grandfather, the famed landscaper Gustav Hermann Krumbiegel, who gave Bengaluru its ‘Garden City’ moniker and who was behind the planning and creation of numerous parks, zoos, coffee estates and palace gardens. His name is still spoken among the royal families, from Baroda to Mysuru. As for Alyia herself, it was a twist of fate that sent her on a years-long journey to discover a rich and storied family heritage – the German landscaper who came to India during the British rule and left a mark that’s still visible today.

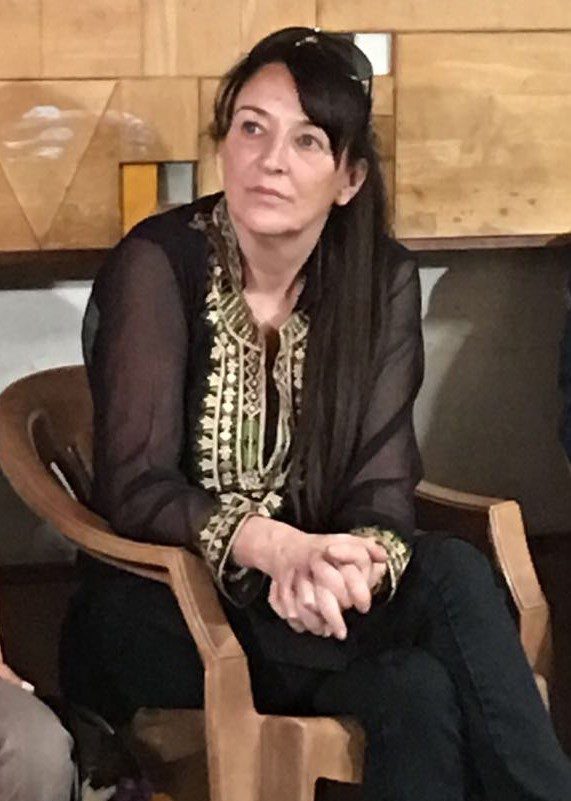

Alyia Krumbiegel

Written in the stars

“I’m a great believer in planets aligning,” she tells me from her office in London, where she lives and was once neighbours with Shah Rukh Khan. Years have passed since we last spoke and Alyia has spent her time unraveling enough family history to fill a book. Which is exactly what she’s doing, along with planning her next trip to India (the pandemic truncated her annual visits). She had grown up hearing stories from her grandmother and never thought much about them. In 2015, Alyia Krumbiegel was at a crossroads in her own life, “I had reached a pinnacle and was at a stage where there were more years behind me than ahead of me.” She decided, almost on a whim, to Google his name for the very first time. “I remember taking off my glasses because I was so surprised,” she laughs.

There was so much to see – the snippets from her grandmother had done no justice to the man, really. She also found an advertisement, posted by Richard Ward of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, trying to find Krumbiegel’s descendants. The first thing next morning, she rang the house and left Richard a message. He called back 20 minutes later to say, “I can’t believe it. I just cannot believe it. We have been searching for you for years.” Alyia had found a renewed sense of purpose, “Learning I was a Krumbiegel, and what that meant, made me a different person. It reinvented my life.”

GH Krumbiegel: Passage to India

Like his great granddaughter, Gustav Krumbiegel’s journey to India was fraught with challenges and plot twists. A horticulturist in Hamburg, he was very keen to work at the Royal Botanical Garden in Kew and wrote to them, Alyia says, no less than 12 times before he was finally accepted. In 1888, he was offered a post at London’s Hyde Park, where he tended to the rose gardens. Finally, he was granted entry to Kew, where he took care of the hothouse, and this is where, Alyia says, “our story starts.”

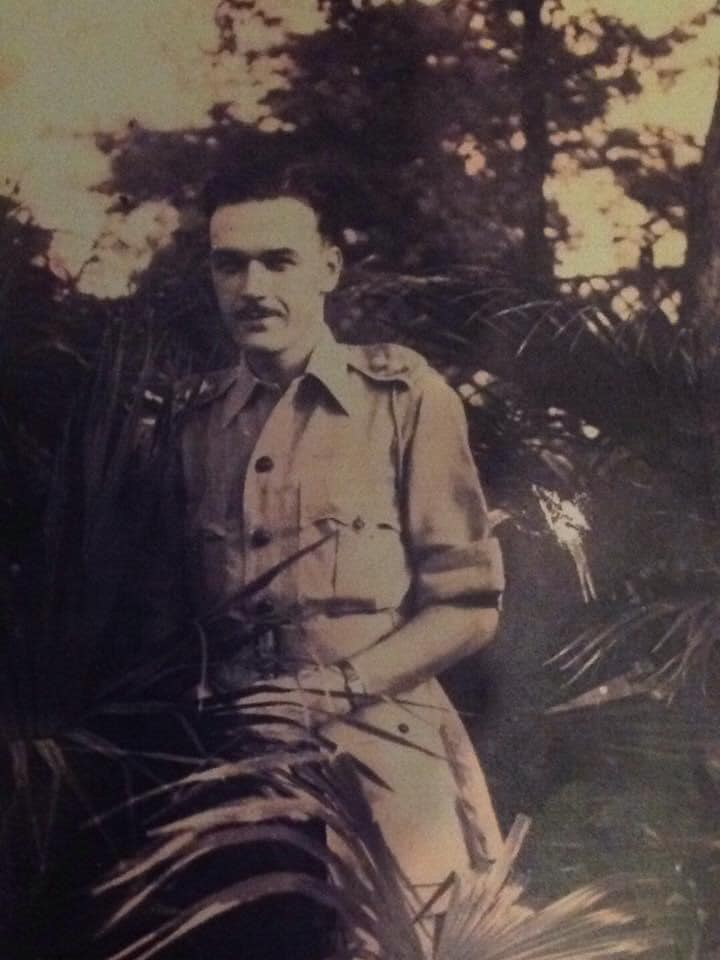

Alyia’s father

Sayaji Rao Gaekwad III of Baroda was, at that time, looking for someone to tend to the state botanical gardens back home. As he visited the gardens in Kew, he learned that Krumbiegel took care of the hothouse and promptly offered him a job. Three months later, Krumbiegel was on a ship to Bombay, from where he arrived in Baroda. “He wrote letters back to Kew in those early days, calling India a remarkable country and praising its rich, red soil, where everything grows, saying there was no need for a hothouse.” Three years later, he sent for Kaite Clara and a couple of hours after her arrival in Bombay, married her.

Krumbiegel worked as the curator of the botanical gardens for the erstwhile princely state of Baroda, succeeding J.M. Henry. “He was asked to find spots for tea plantations in Cooch Behar,” Alyia says. He also landscaped the gardens of the Sayaji Baug Zoo, designed the sunken gardens of the Laxmi Vilas Palace and laid out Baroda’s polo fields. “He also designed water storage reservoirs, because he was very concerned with issues like water conservation. During that time, my great grandmother, Katie Clara, would teach the young princes German. How she had learned fluent German is a bit of a mystery to me because she was British.” Krumbiegel also worked with the Government Botanical Gardens in Ooty and was responsible for the architectural redesign.

Alyia Krumbiegel with Jeetendrasingh G Gaekwad in Mysore

Krishnaraja Wodeyar and finding home in Bangalore

A painting of Krumbiegel and a bust, both commissioned by the Maharajah are still in the Mysore Palace. In 1907, Krishanaraja Wodeyar, the ruler of Mysore, made him an offer and Krumbiegel arrived properly in the South, where he spent the remainder of his time in India. “He became a trusted associate of the royals and was the only man allowed the privilege of a handshake with the Maharaja,” Alyia says.

The famed Brindavan Gardens, the landscaping of the Mysore Zoo and the palaces and Bengaluru’s Lalbagh all bear the touch of G.H. Krumbiegel. In 1912, Krumbiegel became involved with the Mysore Horicultural Society and the Dewan of Mysore appointed him as an architectural consultant despite objections from Mysore’s British Resident. Krumbiegel expanded Lalbagh, spending so much time there that he moved to the premises with his family. “He was the only superintendent to raise his family in the park,” Alyia explains. He revived the Mughal style of gardening and introduced several plants that he brought in from England.

The seed exchange

“Kew had a seed exchange programme, which great-grandfather started when he went to Baroda,” Alyia tells me. In Lalbagh, where he worked another ‘Kew-it’, John Cameron, they scaled up the exchange. The duo obtained seeds from other countries and sent collections to Kew as well as to America. Varieties of mango, including the malgova and varieties of rice went to the United States from Bangalore. In return, he introduced the Rhodes grass, Russian sunflower, soya bean, American maize, Feijoa sellowiana from Paris, Livistonia Australia from Java and several other species. In Bengaluru, the tabebuia and the jacaranda, as well as the majestic rain trees that continue to line the Cantonment area, all bear testament to Krumbiegel’s legacy. He was also among the group that founded the still active Mythic Society in Bengaluru.

G.H. Krumbiegel at the Lalbagh Flower Show

‘Enemy of the state’ and a patriot of his adopted home

When World War II commenced, Krumbiegel was declared an enemy, by virtue of his birthplace, by the British. “He had embraced India and was very vocal about independence for the country,” Alyia says. “The princely royals protected him when the British saw an enemy in every German.”

On two occasions, Krumbiegel was thrown into prisoner of war camps by the British in India. His views against colonialism also resulted in him receiving a severe beating during his imprisonment. “The Maharajah of Mysore saved him from being deported as well.” His wife, Katie, although she was British, was also considered a traitor for having married a German and for a time, Alyia says, “great grandmother and their daughters were under house arrest.”

The end in Bengaluru

In 1952, Krumbiegel, who was then a consulting architect and an improtant advisor in town planning and horticulture died in Bengaluru. He was buried in Hosur Road, at the Methodist cemetery and a road located between two of Lalbagh’s gates was remained Krumbiegel Road in his honour. In 2016, the grave was given a much-needed facelift. Krumbiegel House in Lalbagh remained standing as a ruin until its collapse in 2017, after which the state government created a replica of the structure.

Reviving the legacy

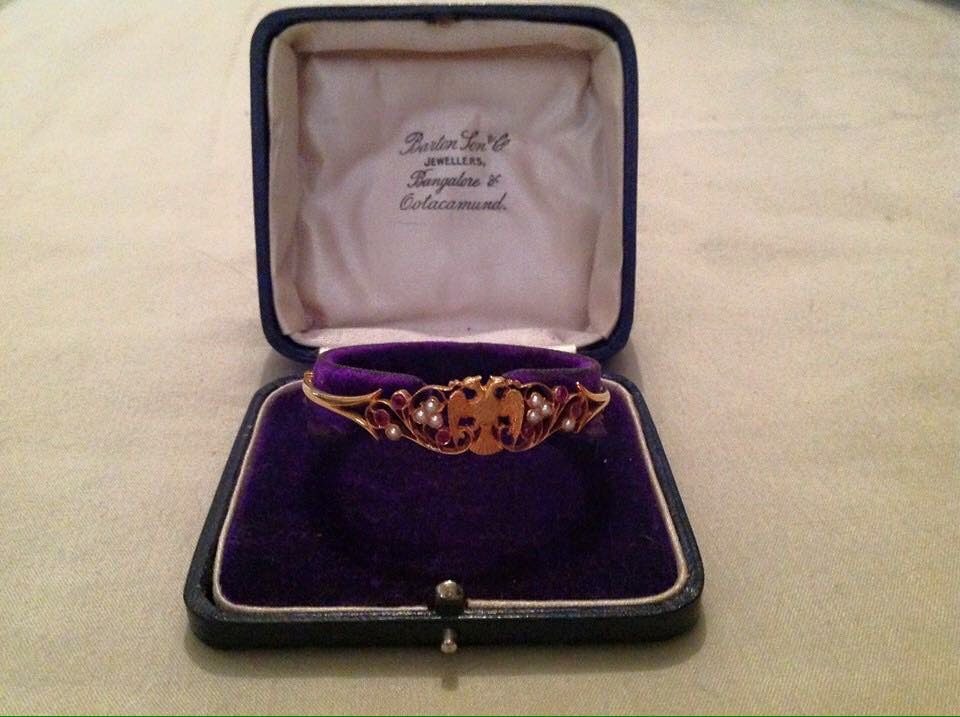

Always on Alyia’s hand is a gold gandaberunda, flanked by rubies and pearls, bearing the two-headed bird that is the royal insignia of the kingdom of Mysore. Now, it is Karnataka’s state symbol as well. “it was a gift from the Maharaja of Mysore to my grandmother Hilda, when she turned 18,” Alyia says. “When she died, I got the bracelet.”

Gold gandaberunda, flanked by rubies and pearls, bearing the two-headed bird that is the royal insignia of the kingdom of Mysore. Now, it is Karnataka’s state symbol. Photo: Courtesy Alyia Krumbiegel

Ever since her first visit in 2016, Alyia, who tries to return each year, has become a vocal voice for preserving Bengaluru’s monumental and green heritage. One of the people she met along the way was Jeetendrasingh Rao Gaekwad, of Baroda, with whom she took a private tour of the Mysore Palace and tea with the queen mother, Pramoda Devi Wadiyar.

“That was a surreal experience,” she says. “We were sitting in the formal lounge of the palace, which was breathtaking. Then she came through, wearing a bright yellow sari and so graceful, she looked like she was floating, not walking. We had coffee and cake together and spoke of all the connections.” She also visited the coffee estate in Chikmagalur that her grandmother had once owned and been made to give up when the British left India.

When she returns, the first thing she does is visit her great-grandfather’s grave. “I like to arrive at half-past three in the morning so I won’t be in traffic.” Alyia describes Bengaluru with great familiarity. After breakfast, she heads to the Methodist Cemetery to place flowers on Krumbiegel’s tomb. “Nobody ever touches it. I think they know that I left it there and they always make sure it’s intact. Even if it’s hanging by one string, it stays there.”

- Follow Alyia Krumbiegel on Facebook