(April 5, 2023) On a scorching summer afternoon in Chandigarh, Shreya Dhillon stood outside her house, refusing to come back inside. Shreya was wearing several layers of clothing, as kids with Down Syndrome often do, because increased pressure helps alleviate their sensory issues. When her mother, Shivani Dhillon, came home, the family was at their wits’ end. Shivani walked straight up to her daughter and began to tell her a story. “Shreya, do you know what happened today? The sun came out and asked if you want to play. Do you want to play with the sun, Shreya?” Shreya turned to lock eyes with her mother, who continued speaking as she led the child back inside.

“I could teach her everything through stories,” Shivani tells me, as we speak – it’s a busy Saturday morning in the Dhillon household and I can hear the sounds of the day unfolding. Shreya walks into the room as well, looking into the camera to greet me with a smile and a cheery “hi!” “She has learned to recognise colours, fruits, the sun, the moon, night and day, all through stories. That’s how she absorbed information.”

That opened a door, for Shreya and for Shivani as well, who began harnessing the power of stories to reach out to children and young adults with intellectual disabilities. A former journalist, Shivani is an award-winning social entrepreneur, founder of the Down Syndrome Support Group India and Samvid – Stories & Beyond. Her latest accomplishment is a book of her own: Extra: Extra Love, Extra Chromosome, with Shreya as a protagonist. It’s a story of fortitude and self-acceptance that transcends age and ability. And it gives readers a momentary glimpse of the courage that neuro-atypical kids like Shreya, as well as their parents, must display every day of their lives.

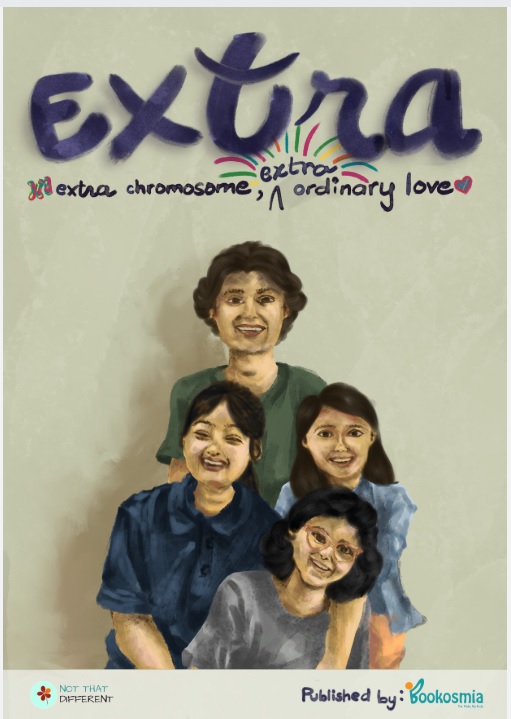

Shivani Dhillon and her daughter, Shreya

The intrepid journalist

Before Shreya was born, Shivani Dhillon was a journalist, chasing stories around the globe, visiting warzones and interviewing high profile people. An anchor with the BBC, Shivani did the work most young journalists dream of doing, but very few realise. “I started in 1999 and joined Zee News as an anchor and reporter,” Shivani says, in her interview with Global Indian. These were in the early days of television news, and new channels were just entering the fray after decades of DD dominating the scene.

After a couple of years in television news in India, Shivani moved to London for a Master’s degree in diplomatic studies. From there, she joined the BBC World Service, also working on documentaries. During those eight years, she married, and gave birth to her first son, who was struggling with health problems. “Once, I had to leave my son for about four days to make a documentary. When I came back, I realised I didn’t want to do this anymore,” she says.

The birth of Shreya

In 2010, Shreya was born with Down Syndrome, as the doctors in the UK had predicted. In the first trimester, they were told there was a high chance their daughter would have Down Syndrome. Shivani was asked to do a test and to decide on a course of action post the results. She refused. “We wanted the child, irrespective of what it may or may not have. We didn’t want to find out.”

The family returned to the UK, in part because of the healthcare system, where proactive staff also understood the toll taken on mothers of disabled children. They would even call to remind her of upcoming counselling and medical appointments. But there was one thing missing – social interaction. They returned to India, going back into the joint family system. Here, Shreya had lots of people to talk to and became a friendly child, her speech developed and she blossomed.

Creating a community

While a strong sense of community did wonders for Shreya, healthcare was another story. “I was thrown into the deep end when it came to therapy, finding the right doctor, the right information and even fellow parents.” The stigma was very high, even educated relatives asked Shivani why she told people about Shreya’s ‘condition’. And she knew that thousands of parents across the country were facing the same thing.

Shivani began printing out flyers with her email id and phone number, talking about DS and appealing to parents with disabled kids. “I was looking for a friend,” she admits. In 2012, she got her first phone call. “I knew I needed to reach out to more people and Facebook was still new then, so I started an online support group.” The group has over 2,500 members now, from India and around the world. “You want to connect to your own people,” Shivani tells me. “There is stigma in our country, even today. In the UK, there was support from the state, the doctors, the therapists. They understand what the parents go through and it felt good. In India, you’re likely to be asked what you ate during pregnancy,” Shivani explains. Those moments of self-doubt are common, “I would wonder if I did actually eat something wrong, partied too much, or didn’t pray enough?” Being able to share experiences with people who had similar lives made a world of difference.

Finding purpose

Back home, Shreya needed to be taught even the smallest things. “You don’t teach neurotypical kids how to walk, they just walk. But kids with DS need to be taught.” She was well-travelled and well-read, with access to all the resources she needed and she could handle the challenges that came her way. “I started thinking about that – I can do so much for my kid but what about the parent who doesn’t have the exposure, the knowledge or the resources? What happens then? I wanted to do something for them.”

We spend our lives trying to figure out what our purpose might be and many of us never do. But in the darkest of times, that purpose might come looking for you. That was the case with Shivani. She started the Down Syndrome Support Group India, and built a loving and supportive community. She organised an international art exhibition, encouraging art as a form of therapy. They celebrated World Disability Day and Down Syndrome Day.

The power of stories

In the Dhillon home, reading a book to the kids was a night-time ritual. And from the time Shreya was a few months old, she had been listening to stories. “I realised she was so engaged and engrossed and learning so much. What she learned, she learned through stories.” During the lockdown, Shivani began doing sessions with disabled kids and young adults, telling them stories as a form of therapy. And during the pandemic, she had her work cut out for her. There were difficult topics to discuss, death being one of them.

“Stories impact them on a fundamental level. It takes time but they start communicating more, become more expressive and their language improves,” Shivani explains. Communication, she says, is one of the biggest challenges, they struggle with reading facial expressions, understanding social cues and understanding emotions. So, twice a week, she would meet groups of ten, tell a story and talk about the story afterwards.

Finding a school

Last year, Shreya was taken out of mainstream education and Shivani Dhillon began looking for a school for her. She found one, on the outskirts of Chandigarh, where teachers and students shared a loving bond. But the building was falling apart. “I knew it was the place for my daughter but she and other kids deserved better infrastructure.”

Shivani oversaw fundraising efforts, raising enough to revamp the school. “We have launched the new school, Discoverability, now,” she says. She works with the principal and the founder to handle the school and Shreya loves being there. “We want to start vocational training for students as well,” she says.

Knowledge is power

It has been a journey full of challenges, Shivani says. “Bringing up a child with special needs is not easy, especially in India. You don’t get invited to birthday parties, and there’s a lot of staring, everywhere we go. I simply walk up to people and educate them. Sometimes that is all it takes. If I hadn’t had a daughter with DS, I might have been oblivious too.” Life may not work out the way you want, she says. “When I had my daughter, I saw those beautiful eyes and thought, the boys are going to be lining up for her. That’s not going to happen but she has brought so much joy and happiness to our lives.”

Transformation through crisis

Finding purpose, Shivani says, has been a spiritual journey. She’s a believer in karma, not in a ‘resigned-to-her-fate’ kind of way but in the sense that everybody has a purpose, a reason for living. “When you have that understanding, of something greater, you don’t ask those questions. I can’t give Shreya many of the tools I use to cope with challenges but I do know that the one thing she can fall back on is a connection to a higher being.”

- Follow Shivani Dhillon on LinkedIn