(March 8, 2023) “Looking through the camera, focusing on a subject, and isolating it from its surroundings. These were the things that attracted me. The viewfinder of the camera attracted me to photography.” This quote by Homai Vyarawalla is the testimony of her love for the art of photography.

Picture this: It is the early 1900s. A woman in a sari takes up a Rolleiflex camera and cycles across the city to click photographs. Some men snigger at her, others completely ignore her for she is no authority on the subject or the object of her fascination—her camera. But she sticks her ground and captures moments and emotions on her lens that speak to millions of people. This is the story of Homai Vyarawalla, India’s first woman photojournalist. She broke into the male-dominated profession of photography and proved her mettle with every frame that she composed.

A meeting that changed her life

Born in 1913 in Gujarat to a Parsi family, Homai’s childhood was mostly spent on the move as her father was an actor with a travelling theatre group. It was only later that the family settled in Bombay where she completed her studies. Owing to her humble background, she often shifted houses and had to walk long distances to reach her school. Despite the social prejudices and barriers prevalent in those times, Vyarwalla was keen to finish her matriculation at a time when she was the only girl in a class of 36 students. A young Homai then enrolled herself in St Xavier’s College for a degree in Economics, after which she opted for a diploma from the prestigious JJ School of Art.

Homai Vyarawalla with her still camera

It was here that she met Maneckshaw Vyarawalla, a freelance photographer, in 1926: the man who changed the course of her life. He not only introduced her to the art of photography when he gifted her a Rolleiflex camera but also married her in 1941. The camera became Homai’s object of obsession as she started capturing her peers at college and Bombay in general through her lens.

The initial struggle

It was under Maneckshaw, who was then working with The Illustrated Weekly of India and The Bombay Chronicle, that Homai started her career in photography as an assistant. Her initial black-and-white photos captured the essence of everyday life in Bombay and were published under the name of Maneckshaw Vyarawalla as Homai was then unknown and a woman. The publishers believed that Maneckshaw’s gender gave the photos more credibility, reported the Homegrown.

This oblivion on the part of men who failed to recognize her potential was a blessing in disguise for this Parsi woman. At a time when women were not taken seriously as photojournalists by men, their ignorance helped the Global Indian take the best pictures without any interference.

“People were rather orthodox. They didn’t want the women folk to be moving around all over the place and when they saw me in a sari with the camera, hanging around, they thought it was a very strange sight. And in the beginning, they thought I was just fooling around with the camera, just showing off or something and they didn’t take me seriously. But that was to my advantage because I could go to the sensitive areas also to take pictures and nobody will stop me. So, I was able to take the best of pictures and get them published. It was only when the pictures got published that people realized how seriously I was working for the place,” said Homai.

Creating history through her photos

The World War II and the events that followed gave Homai many opportunities to capture its political consequences in India. It was a time when women were coming out in the public domain as they played agents of change, and the photographer in her captured every event in its true essence. Soon she began to draw attention with her body of work which was published under the pseudonym Dalda 13.

In 1942, she and her husband were commissioned by the British Information Services as photographers which took them to Delhi. The capital remained home to the Vyarawallas for almost three decades. Running their business from a studio in Connaught Place, the Vyarwallas captured history in the making. This was the beginning of Vyarwalla’s long innings as the first female photojournalist in India.

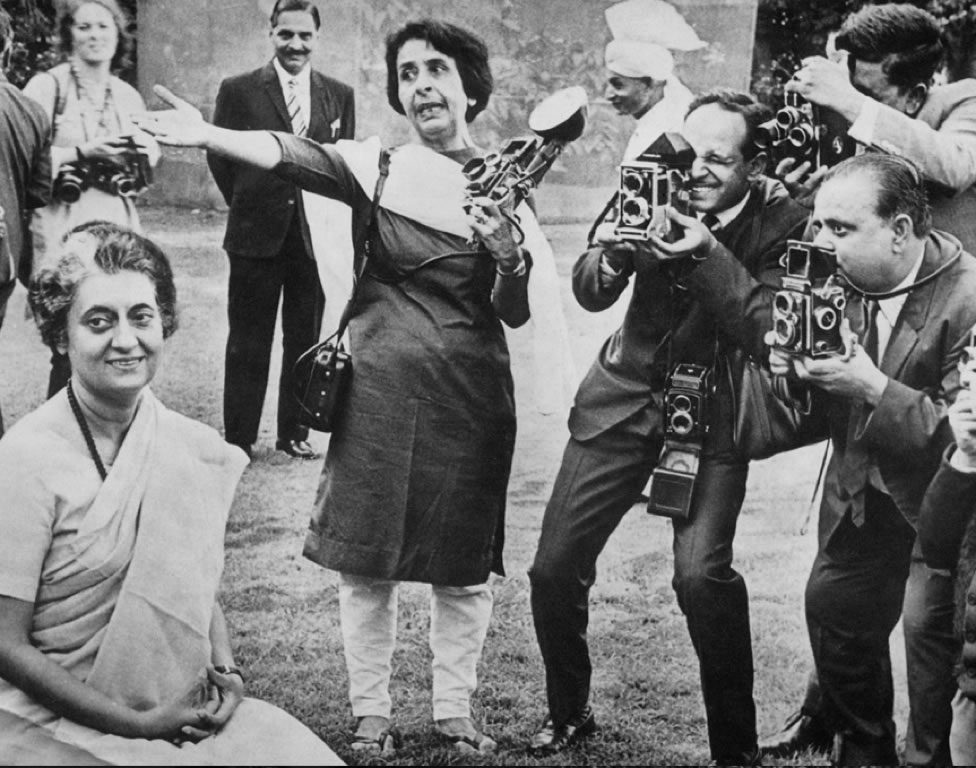

Homai Vyarawalla clicking Indira Gandhi during an event.

Clad in a sari with a Rolleiflex by her side, Homai cycled across Delhi to capture moments that would define the contours of 20th Century history. Her camera, which documented the last few days of the British empire and birth of a new nation, reflected the euphoria of Independence along with the unresolved issues that came with it. From photographing leaders like Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru to capturing independent India’s first flag being hoisted at the Red Fort, Homai gave India some of its most iconic photographs. The unique opportunity of capturing intimate political moments was something that she earned with integrity, dignity and perseverance.

By the early late 40s and mid 50s, Homai’s demure persona was present at every significant soiree, documenting historical events and capturing big names like Martin Luther King Jr, Jacqueline Kennedy and Queen Elizabeth II.

Homai had become so popular that Life Magazine approached her in 1956 to photograph the 14th Dalai Lama when he entered India for the first time through Nathu La. With a camera on her back, Homai took a train to Darjeeling and after a five-hour car drive, she reached Gangtok to take the perfect shot. But it was her courage to travel alone with no place to stay in times when women’s safety was an issue was a testament of her strength and dedication to her work.

1956: The Dalai Lama enters India through a high mountain pass. He is followed by the Panchen Lama. pic.twitter.com/W2yIZC0zqZ

— #IndianHistory (@RareHistorical) December 3, 2015

The photographer who made Nehru her muse

Homai had photographed many eminent personalities but none were as captivating to the photographer’s eye than Jawaharlal Nehru, who was her muse of sorts. She found Nehru a photogenic person and captured the many phases of his life. Such was the trust that Nehru let her capture him even in his unguarded moments. One of them led to the iconic photo of Nehru lighting a cigarette for the British Commissioner’s wife, while one dangles from his own mouth.

She even captured Nehru in his last moments. “When Nehru died, I felt like a child losing its favourite toy, and I cried, hiding my face from other photographers,” she said.

After creating some profound and iconic moments through her lens, Homai hung up her boots in 1970 shortly after the death of her husband. With yellow journalism picking up, Homai bid adieu to her career.

Homai Vyarawalla clicked this photograph of Pandit Nehru

“It was not worth it anymore. We had rules for photographers; we even followed a dress code. We treated each other with respect, like colleagues. But then, things changed for the worst. They were only interested in making a few quick bucks; I didn’t want to be part of the crowd anymore,” she added.

After giving up her 40-year-old career, Homai gave her collection of photographs to the Delhi-based Alkazi Foundation of the Arts. Later, the Padma Vibhushan-awardee moved to Pilani with her son. It was in January 2012 that she breathed her last after suffering a long battle with lung disease.

Making a name for oneself at a time when women were relegated to the confines of the house, Homai Vyarawalla gave the world a perfect example of a woman who was ready to take on the world with her talent.