Thirty years had passed since Bem Le Hunte first stood on the doorstep of Mongrace in Kolkata, her first school. Her spirits lifted as she heard the children inside singing about “a little duck with a feather in its cap,” a song she still remembered. Back in India to write her second book, Bem found herself drawn to the school once more, wanting very much to find Aunty Grace and say thank you. The door swung open and a woman stood before Bem, who told her what she wanted. To Bem’s surprise, the woman burst into tears – Aunty Grace had just passed on. She might not have had the chance to see her old teacher again but her timing was startling, nonetheless. It’s the sort of thing that happens in Bem’s world – her own story is as riveting as the ones she likes to tell in her novels, which often draw from her real-life experiences.

Now an internationally-acclaimed author and academic, Bem is at the forefront of futuristic education herself, as the founding director of the award-winning Bachelor of Creative Intelligence and Innovation at the University of Technology, Sydney. Half Indian, half-British and totally Australian by choice, Bem Le Hunte’s story unravels like a Gabriel Garcia Marquez novel, a heady mix of mysticism and materialism.

Bem le Hunte

Building a brave new world

Bem moved to Australia when she was 25, tired of her life in the UK. Within a month, she had met her would-be husband, Jan, whom she married soon after, and also landed a full-time job as a lecturer in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at the University of Technology (UTS). There, she is the founding director of a first-of-its-kind course on Creative Intelligence, that she says is “informed by consciousness based education.” A long-time practitioner of yoga and transcendental meditation, she tells Global Indian, “My Curriculum for Being informs everything I do. It informs how I write and the learning experiences I design.”

She describes it as a “creative response to this dilemma of our time.” Through a transdisciplinary approach combining 25 different degrees, it’s an attempt to “future proof” careers in a rapidly changing world, one with which the education system has not yet managed to keep pace. “You have to do the ontology of learning, not just the epistemology, it’s about the being, not the doing,” Bem explains.

Schooling systems the world over continue to emphasise rote learning, gearing students up for the competition-driven ecosystem of western capitalism. That won’t work, Bem feels, in the workplace of the future, where “you’re going to do 17 different careers in totally different fields. We aren’t future proofing them if we’re only training them for one.” The other response is to create an ecosystem of “radical collaboration.” Here, the unity of all disciplines is the goal. Students work in transdisciplinary teams, an engineer collaborates with a communications person, a businessperson with a healthcare person and “they tackle a challenge together that globally affects a lot of people.”

Course Director, Associate Professor Bem Le Hunte accepting the BHERT Award.

Early life

Bem was born in Kolkata, to an Indian mother and English dad. Her grandfather ran a mining company that he eventually sold to the Birlas and was “quite an international person, who had studied at Bristol University.” Her mother went to Cambridge, where the gender ratio at the time was one woman to every 10 men. “I’m not just the product of a tiger mum, but also of an English father. So I was half tiger and half pussycat,” she grins. “My mother was very motivated about my education and encouraged me to write. I had a good mix of ‘relax and do what you want’ and this really motivated learning.”

When she was four years old, the family moved to the UK. Every summer though, they would return to Calcutta or Delhi where a young Bem would dip into her grandmother’s book collection, reading Sri Aurobindo and Swami Vivekananda late into the night. At their home in Wales, Bem created a cathedral temple in the forest at the edge of their backyard, “a green space to encounter the natural world and the continuity of self that it gives to you.” This mysticism has only grown stronger – her life is peppered with stories of healers, quests and spiritual journeys. One hour each day for the past thirty years has been spent in transcendental meditation. Her grandmother, Bem says, learned meditation from Maharishi Mahayogi himself. Don’t, however, mistake her for a new-age hippie, her approach is one of discovery and questioning, of exploring the mystic realms of the human mind rather than blind faith in the unknowable.

Breaking away from mainstream education

A gifted student, Bem found the mainstream education system quite unfulfilling and in high school, informed her mother she wanted to quit, taking her A-Levels after being home-schooled. She learned English literature from her mother, who, incidentally, was among those responsible for the English A-levels curriculum. After a year spent studying journalism and realising it wasn’t for her, she moved on to Social Anthropology and English Literature at Fitzwilliam College, Cambridge.

“I wanted to go on to do other things,” she says. “Education has a way of holding people back. I know that Indians see it as a key to a door but it has a strangulation effect, it can kill your creativity, too.” Over the [ast few years, Bem has returned to the problem, this time as a champion of new ways of learning. Her year-long experience with journalism, which she agrees, helped her craft her writing, “was quite restrictive creatively.” So, she switched to social anthropology instead. All in all, Cambridge was an exciting time, in an interview, she speaks of how she starred in a student movie, befriended controversial artist Marc Quinn, lived with the octogenarian Doctor Alice Roughton in a house filled with people from around the world where “we ate food she rescued from school dinner leftover bins.”

Bem Le Hunte

Arrival in Australia

She went on to travel the world, visiting Japan and then Chicago, before returning to Delhi to make films on women’s development for the United Nations. At 25, she moved to Australia and began working as a lecturer at UTS and also met her husband. A month after their wedding in Rajasthan and a communal honeymoon in the desert, Bem contracted Hepatitis A. She was rushed back to London, to an isolation ward, where her condition showed no improvement. In a panic, Jan recruited a healer who offered to help and Bem, who was asked to sign papers acknowledging that she would die if she left hospital, moved to his house. The “polarity therapy” proved effective and brought with it a new fascination for Bem – alternative therapies.

In 1995, heavily pregnant, she was asked to oversee the Australia launch of Windows 95. During that time, she was working in a range of industries, and also focussing on educating students and clients on digital innovation. “The Windows launch was scheduled for the same day as my due date,” she says. Three years later, when Windows 98 came along, so was her second child. This time, she decided on maternity, to “sack my clients and go live in the Himalayas. I wanted to write that book so badly and at the time I didn’t know what it was going to be. I placed radical trust in the creative process. It’s one of the things I believe in. Mystery has to remain mysterious and I enjoyed the creative process of being able to stay in the mystery for longer.”

A time of renunciation and a literary career

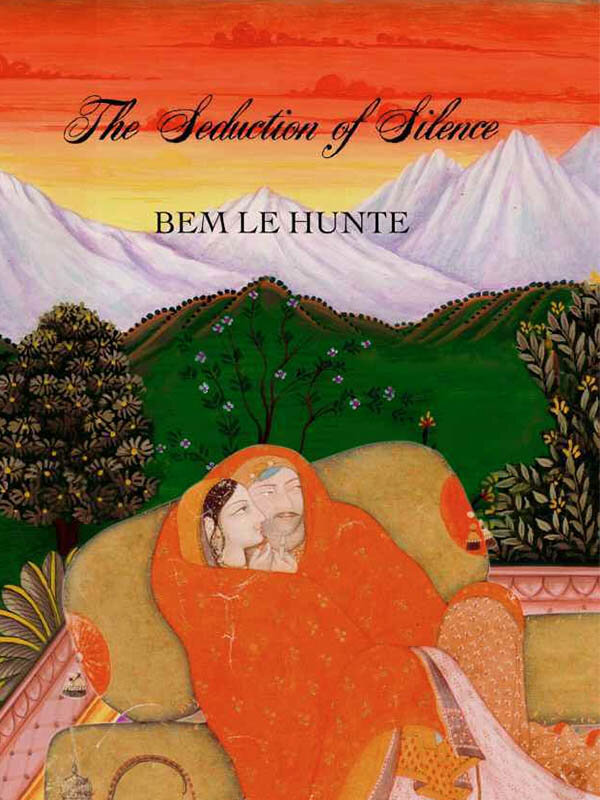

Living in the mountains, she wrote The Seduction of Silence, a multi-generational, magical saga that takes the reader on an intensely emotional and spiritual journey. The story begins with Aakash, a sage in the Himalayas who continues to offer his teachings even in death, through a medium. Over generations, the family oscillates between the spiritual and the worldly, coming full circle through Aakash’s great granddaughter, who returns to the Himalayas.

“If we were to believe that our lives are not magical,” Bem remarks, “We would be deluding ourselves. Unhealthy people have a very realistic view of the world, for the most part, we have magical minds. If we didn’t, advertising wouldn’t work.” The book did well, and was shortlisted for the Commonwealth Writer’s Prize. In 2006, she published There, Where the Pepper Grows, a World War 2 tale about a Polish-Jewish family’s stay in Calcutta during their journey to Palestine. Her third novel, Elephants with Headlights, came in 2020.

Bem continues to live in Sydney with her husband, Jan and their sons, Taliesin, Rishi and Kashi.

A beautiful and honest article describing the most extraordinary woman I’ve ever known!