(April 13, 2023) It was the biggest news of not just 2012, but of the century. A group of scientists, in a landmark event, had discovered the Higgs boson particle (also known as the God particle) – a discovery that lay the foundation for the matter that forms us and everything we see around us in the universe. Scientists from across the globe rushed to congratulate the team behind such a historic discovery, among whom was Dr. Archana Sharma, the Indian staff scientist at CERN who was involved in the experiment.

As she connects with me over a call from Geneva for an interview, I ask Dr. Sharma something that had been on my mind for a long. The STEM education gender gap in India is glaring even today. How challenging was it for her to pursue a master’s in nuclear physics back in the early 80s? “Well, I don’t think any journey is easy. Neither was mine,” says the scientist, adding, “While I was pursuing my Ph.D., most girls my age were getting married. Today girls can put their foot down and do what they want to, but the generation that I belong to is very different. People would say, ‘jhola leke chali hain physics padhne, kya yeh Nobel Prize layengi?‘ Though there was immense support from my family, from time to time I would hear people say, ‘She’s too educated, who is going to marry her?’ But, whatever the challenges, you just need to clench your teeth and carry on.”

A globally recognised scientist for her pioneering work on micro-pattern gaseous detectors, Dr. Sharma is currently a senior CMS physicist European Organisation for Nuclear Research, known as CERN in Geneva, Switzerland. She is also the head of relations between CERN and other international organisations. The Global Indian, who received the prestigious Pravasi Bharatiya Samman in 2023 for her ‘outstanding contribution to science and technology’ and in recognition of her ‘valuable contribution’ in promoting the honour and prestige of India, dedicated the award to the students of India saying that her Indian roots and upbringing have helped her serve the world as one family.

A small-town girl with big dreams

Born in Aligarh, Dr. Sharma was always a brilliant student. “I grew up in Jhansi and completed most of my school education from there. Both my parents were teachers – my father taught mechanical engineering, and my mother taught economics and geography. They were the ones who pushed me towards picking science as my career path. I came from a middle-class family, so good education was quite important and my parents saw to it that I got that.”

After finishing school, Dr. Sharma moved to Varanasi for a bachelor’s in physics from Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi where she also did her master’s degree. While it might look easy now, back in the 80s, it wasn’t common for girls to pursue a career in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) fields. “Firstly, I loved the subject, and just decided to follow my heart to do a masters in nuclear physics. I was curious to learn more about what makes the world around us and wanted to explore the field,” says the scientist.

However, while education is one thing, finding a job is another. Despite being a “good student, who had secured gold medals”, the scientist faced several challenges after finishing her master’s. “Physics is not a top career path in terms of giving immediate rewards. There were students in my class who took electronics and computing and got a job even before finishing their master’s. It was a frustrating time for me because I wanted to stand on my own feet and there was no future in sight. For about two to three years, I didn’t get any suitable job. Moreover, I didn’t get admission to the best Universities to pursue my Ph.D. But as they say, there is a rainbow after the rain. I was lucky and got a chance to do Ph.D. at Delhi University,” the scientist says.

The land of the Alps

While she was pursuing her Ph.D. at DU, Dr. Sharma got an opportunity to attend a workshop in Trieste Italy, in 1987 and visit CERN. And that was a turning point for her. “A senior professor who gave a lecture at the workshop announced that the best student would be allowed to work at CERN in Geneva for six months. It was a big opportunity and couldn’t just let it go. So, I worked hard and managed to get this opportunity. I convinced my parents about me going to Geneva, and my in-laws were also quite supportive,” shares the scientist, who later won a fellowship to come to CERN for three years and landed right in the group of detector development led by Georges Charpak (Physics Nobel Laureate, 1992).

Dr. Sharma receiving the Pravasi Bharatiya Samman from President of India, Droupadi Murmu

To work at CERN is a dream for scientists across the globe, and Dr. Sharma was living it. In a first Sharma was exceptionally employed in 2001, by CERN, as an Indian. But the dream had its challenges. “The cultural shift wasn’t so much of an issue. Being raised in a multicultural society, Indians are well aware of how to accommodate and adapt to other cultures. Language, however, was a bit of a barrier. I had to learn French, which was a steep learning curve for me,” she recalls.

However, language wasn’t the only barrier. Lacking practical knowledge of instrumentation and building scientific instruments, the scientist found herself in a bit of a tight situation in Geneva. She reminiscences, “Back in those days, there was a lack of infrastructure in the Indian universities. So, my preparation wasn’t as good as I thought it was when I reached CERN. I had to learn and understand how advanced instrumentation worked, now that I had to use them regularly, and to make sense of the work that I was supposed to do.”

To overcome the challenge, Dr. Sharma enrolled and earned a second doctorate (D.Sc.) in “Instrumentation for High Energy Physics” from the University of Geneva in 1996 and later also got an executive MBA degree from the International University in Geneva in 2001. “However,” she adds, “The ease of performing research and development work at CERN, was a pleasant surprise for me. The work culture and professionalism here is amazing.”

The discovery of the God particle

CERN, in collaboration with over 10,000 scientists and hundreds of universities and laboratories, built the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) between 1998 and 2008, to allow physicists to test the predictions of different theories of particle physics. “My work was to prepare tools and techniques for looking at the processes relating to the big bang.”

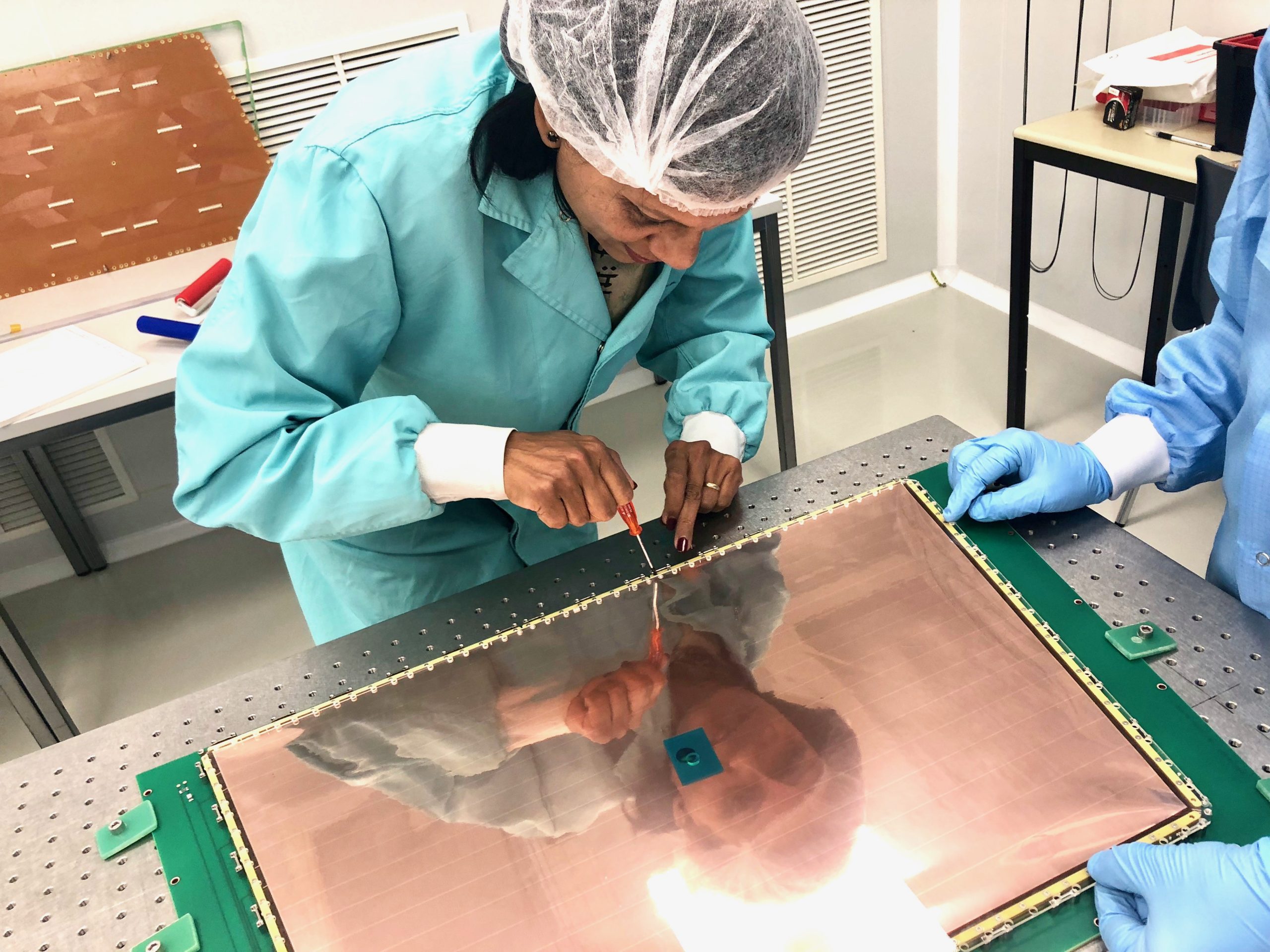

Dr. Sharma at the CERN Large Hadron Collider

She explains, “The Universe is made up of fundamental particles of matter, which contains quarks and gluons, and forces by which they act on each other. In the 1960s, the Higgs mechanism was invoked to explain how particle gets mass. So, to prove that the Higgs boson exists, we needed to do a very large experiment and the LHC had an ambitious goal of finding this boson. In the 90s, I was working on R&D of detectors and techniques, which were later used to confirm the existence of the Higgs boson particle. Of course, I did not know at the time that I was contributing to this huge experiment. I worked on the Compact Muon Solenoid (CMS) experiment, and my responsibility was to ensure that the detectors for the muon system would be built, installed, commissioned, and then operated when the LHC switched on.”

On July 4, 2012, a historic seminar was held to announce the detection of the Higgs boson. “I got up early and reached CERN at 5 am to get a seat at the auditorium, only to find that I couldn’t even enter the jam-packed venue. It was the most amazing experience of my life,” she shares.

Ask her about the theories floating around at the time that the LHC could potentially create a black hole and the scientist quips, “Oh, they were blessings in disguise. You know how they say ‘any publicity is good publicity’. This news gave us scientists a way to reach out to the public and explain to them that collisions much greater than the hadron collider happens from cosmic rays as well. And yet, we and the Universe are still here. So, these theories helped us bust many myths around the black hole formation.”

Empowering young people

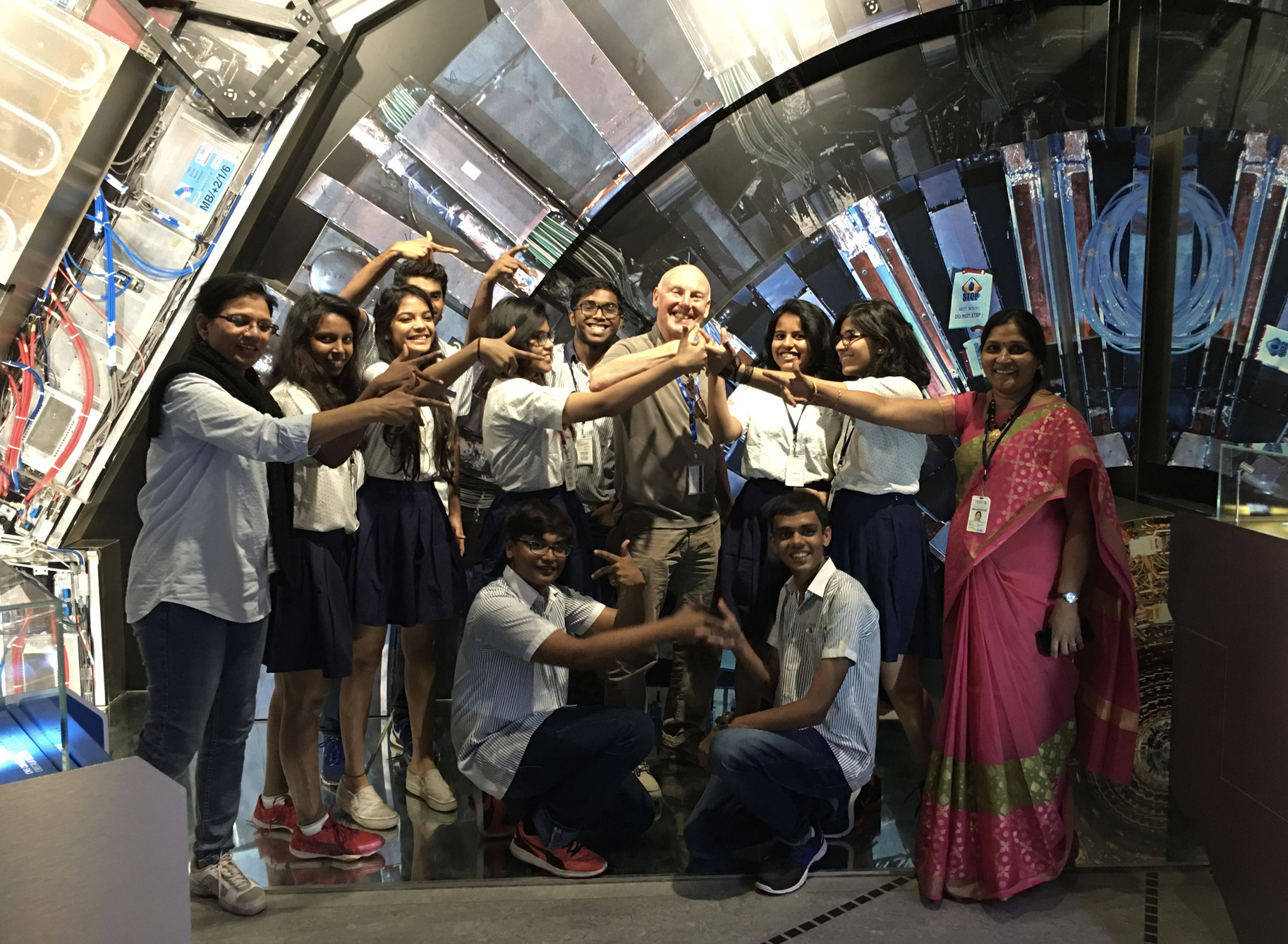

In 2017, India became a member state of the CERN and Dr. Sharma has been coordinating collaborations, and even guiding Indian interns at CERN. Running her own NGO, Life Lab Education and Research Foundation, the scientist is working towards creating partnerships with educational institutions for the benefit of underprivileged students. “I come to India very frequently, giving my time to schools and other science and engineering institutions to give talks and interact with students, teaching them whatever little I can about particle physics, and how technology and innovation can impact society and sustained development goals,” Dr. Sharma says.

Dr. Sharma with Indian school students

Currently working on the CMS experiment in the Large Hadron Collider, developing a new muon system called GEM (Gas Electron Multiplier), which can detect muons in the outermost layer of the CMS, the scientist has mentored a large number of Ph.D. students and has authored or co-authored over 1200 publications. Her dream is to touch the lives of as many students as possible and bring advanced medical applications from particle physics in mainstream education, diagnostics and treatments.

- Follow Dr. Archana Sharma on Twitter