(December 11, 2024) “What’s the price of tur dal in Gulbarga,” S.M. Krishna asked the district collector of Gulbarga, back in 1999 when he was the Chief Minister of Karnataka. That seemingly mundane question actually marked a new era in government administration. On December 1 1999, the Chief Minister had launched video-conference facilities in the state, bringing nine districts into its network. By working with the Indian Telephone Industries and the Department of Telecommunications, S.M. Krishna was able to speak to officials across the state through his computer. This was decades before words like ‘e-governance’ and ‘digitization’ had come into vogue, and even mobile phones were largely unheard of by the common man. During his five years as the Chief Minister, S.M. Krishna put Bengaluru on the global map as an IT hub, transforming the ‘Pensioner’s Paradise’ into the Silicon Valley of the east.

From there, he went on to serve as External Affairs Minister under UPA 2, and in the span of one year, met 89 dignitaries from around the world. In 2010, he facilitated visits to India by the heads of state from all P-5 countries at the time – Barack Obama, Vladimir Putin, Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao, French President Nicolas Sarkozy and British PM David Cameron. S.M. Krishna, an icon for Karnataka, the Global Indian who brought about the country’s IT revolution and gave India a standing in global politics, passed away at his home in Bengaluru on December 10, 2024.

Early Life and Education

Somanahalli Mallaiah Krishna was born into an agrarian family on May 1, 1932, in Somanahalli, a small village in Mandya district, Karnataka. Krishna’s formal education began in local schools in Mandya, where he quickly excelled in academics and earned himself admission to Maharaja’s College in Mysore, one of Karnataka’s premier institutions. Here, he earned a Bachelor of Arts degree, focusing on history and political science, and developed a keen interest in public service.

S.M. Krishna graduated from Maharaja’s College, Mysore, and then came to Bengaluru to obtain a law degree from the Government Law College. From there, he moved to the US to study humanities at the Southern Methodit University Dallas, and then went to George Washington University as a Fulbright Scholar. He was politically active even as a student in the US.

In 1960, when Krishna was a 28-year-old student in the US, Democratic leader John F Kennedy was running for President. Krishna wrote to Kennedy, offering to campaign for him in areas dominated by Indian Americans. Kennedy went on to win the election, becoming one of the most popular presidents in US history, but did not forget the efforts of this proactive young law student from Mysore. He wrote to Krishna in a letter dated January 19, 1961, saying, “I hope that these few lines will convey my warm appreciation of your efforts during the campaign. I am most grateful for the splendid enthusiasm of my associates. I am only sorry I have not been able to personally thank you for the excellent work which you performed on behalf of the Democratic ticket.”

With the fire for politics already ignited in him, S.M. Krishna returned to India and made his own entry into the political scene. Upon returning to India, Krishna brought with him not only a degree but also a renewed determination to contribute to Karnataka’s development. His early experiences laid the groundwork for his future leadership, combining a rural upbringing with global exposure.

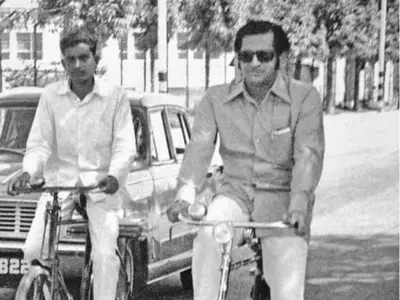

A young S.M. Krishna riding to the Vidhana Soudha in Bengaluru. Photo: The Hindu

Political Career and Rise to Leadership

Krishna’s rise in politics began in 1962 when he was elected to the Karnataka Legislative Assembly as a member of the Indian National Congress. Representing Mandya, Krishna focused on rural development and education, two areas close to his heart. His ability to connect with people and his commitment to development quickly earned him recognition within the party.

In 1971, Krishna was elected to the Lok Sabha, representing the Mandya constituency. During his time in Parliament, he was appointed Minister of State for Industry under Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. This role gave him firsthand experience in policymaking and industrial growth. Krishna’s tenure in Delhi deepened his understanding of the economic policies that could drive India’s modernization.

Returning to state politics in the 1980s, Krishna held several key portfolios, including Finance and Urban Development. He gained a reputation for being a reformist leader who prioritized results over rhetoric. His work in urban planning, particularly in Bengaluru, set the stage for his future leadership.

The CM who transformed Bengaluru

When S.M. Krishna took office as Chief Minister of Karnataka in 1999, the world was in the middle of the dot-com boom, which had begun in 1995. The internet, digital communication, and globalization were reshaping economies across the world, and investors and stock markets alike were bullish about tech startups in California, which included companies like Amazon. While India was just catching on to internet tech, the country had already seen significant economic reforms post the liberalisation of 1991, which opened up markets and positioned the country as a growing power in the global economy. What’s more, while Bengaluru showed great promise, Andhra Pradesh already had a headstart on the tech bandwagon.

“When I assumed office as CM, there was keen competition from Hyderabad under Chandrababu Naidu. He had made tremendous strides in taking technology to the erstwhile Andhra Pradesh. I saw the developments we were making and the growth of the big IT companies, like Infosys and Wipro. So I said why should we not utilise their leadership and their innovative politics,” SM Krishna told The New Indian Express in an interview. Bengaluru had already shown promise as a global IT leader, with two of India’s most successful tech companies, Infosys and Wipro, headquartered here.

S.M. Krishna with Micosoft founder Bill Gates and Infosys co-founder Narayana Murthy

Yet, despite this early success, Bengaluru faced immense challenges in terms of infrastructure, traffic congestion, a nd urban planning. These issues posed a real threat to the city’s ability to handle the rapid expansion of the IT sector. To address these issues, S.M. Krishna recognized the need for bold leadership and strategic reforms.

Krishna’s first call was to Narayana Murthy. “I approached Murthy of Infosys to be on the CM Commitee on IT-BT,” he said. Murthy was more than happy to take up the offer, and wanted to give back to his hometown, Mysuru. After that, Krishna called the founder of Wipro, Azim Premji at his office in Sarjapur, and requested an appointment with him. “He asked where I was calling from and I said I am speaking from Vidhana Soudha. He asked me, “Have you seen the condition of the road in Sarjapur”, and explained I would take half a day to visit his office and come back. Then I asked the chief engineer, Public Works Department, to go to Sarjapur and see that the roads are all set right,” Krishna recalled.

The rapid growth of the IT sector strained the city’s roads, utilities, and urban planning. Krishna’s measures focused on improving connectivity through projects like the Outer Ring Road and flyovers, addressing traffic, and facilitating IT growth.

Krishna’s approach was to bring the captains of the IT industry to the fore in the race to make Bengaluru a global tech hub. He founded the Bangalore Agenda Task Force and appointed Nandan Nilekani as its chairman. “We used to meet every six months. We set targets for Bangalore’s growth, and there was accountability, and accountability became very pronounced.”

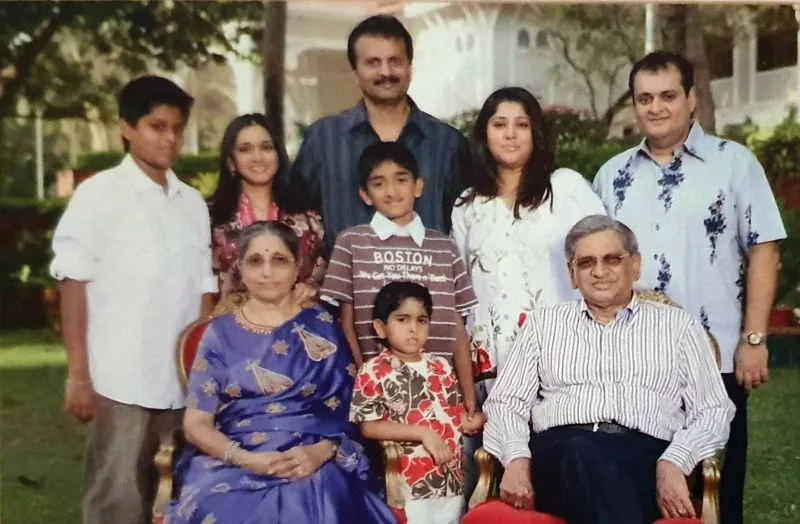

S.M. Krishna with his wife, daughter and son-in-law, VG Siddharth, the founder of Coffee Day

For the first time in a long time, Karnataka had a political class that did not drag its feet over the smallest things, where accountability and growth were front and centre on the leadership agenda. His administration streamlined business processes, providing a conducive environment for IT companies while modernizing Bengaluru’s infrastructure, setting the stage for its future success. “That was how Bengaluru developed, and Chandrababu Naidu himself said Bangalore was the hub of IT-BT,” Krishna said.

Legacy and Continuing Impact

By the time Krishna left office in 2004, Bengaluru had firmly established itself as India’s IT capital. The policies and projects initiated during his tenure laid the foundation for sustained economic growth, transforming the city into a global symbol of India’s technological prowess.

Krishna’s critics have pointed out that rapid urbanization brought challenges such as traffic congestion and uneven development. However, his supporters argue that these are inevitable byproducts of progress and that his vision for Bengaluru created opportunities that outweighed the drawbacks.

After serving as Chief Minister, SM Krishna continued his political journey as India’s External Affairs Minister from 2009 to 2012. In this role, he further championed India’s global engagement, strengthening the country’s ties with other nations. However, his contributions to Bengaluru remain his most enduring legacy.

Photo: Creator: Pete Souza Official White House Photo / Wikimedia Commons

After 46 years, S.M. Krishna left the Indian National Congress in 2017 after a long and distinguished career. His decision was driven by growing dissatisfaction with the Congress leadership, especially after the party’s declining influence in Karnataka. Krishna expressed disappointment over the party’s internal dynamics and its inability to address the state’s concerns effectively. He joined the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in 2017, citing the BJP’s commitment to national development and his belief that the party would be better positioned to address Karnataka’s issues. His move was seen as a significant shift in Karnataka’s political landscape.

‘Visionary’, ‘statesman’, the ‘gentleman politician’—these descriptions became synonymous with S.M. Krishna during his lifetime. They will continue to remain a part of the legacy of the man who reshaped the history of Bengaluru, and India, on the world stage.

Read a similar story of:

Mrutyunjay Mohapatra, building India’s global reputation in meteorology.

Atul Temurnikar, transforming education for Indian expats in Singapore.