(March 31, 2025) Only Dalí could ask for a baby elephant as payment for designing a limited-edition ashtray for Air India, flown all the way from India to Geneva in Switzerland, and then trucked from there to Spain. Decades later, recently over 200 of his surreal wonders arrived in New Delhi for an exhibition. Read on to discover fascinating insights about the artist, shared by the exhibition’s curator:

One day in the summer of 1963, renowned Spanish surrealist painter Salvador Dali found a magnificent octopus on the shore of the Mediterranean Sea, right in front of his house.

Working on the theme of Greek mythology back then, he immersed the dead animal in acid and placed it on a copper plate. The animal imprinted its shape and served as the basis for the Medusa engraving, to which he added a magnificent profile face and a seductive body.

“He created this masterpiece for my father. Salvador Dali was an artist who constantly experimented with new techniques and ideas,” smiles Christine Argillet, curator and caretaker of the Argillet Collection, in a chat with Global Indian.

Salvador Dali

Christine recently brought to India one of the largest exhibitions of Salvador Dali’s works which gave art aficionados a peek into the deep temperament of the Spanish surrealist painter.

An expansive collection of more than 200 of his original sketches, etchings and water colour paintings, were on display at Masarrat Gallery, New Delhi. “I had been thinking of showcasing this collection in India for a long time. It took about 10 years to organise the exhibition,” informs Christine, the daughter of Pierre Argillet, a French collector who was also Dalí’s friend and publisher.

Known to be eccentric, quirky and whimsical Salvador Dali, a supremely gifted artist created some of the most well-known surrealist works between 1929 and 1973, including his most famous masterpiece The Persistence of Memory. There are two major museums devoted to Salvador Dalí’s work: the Dalí Theatre-Museum in Figueres, Spain, and the Salvador Dalí Museum in St. Petersburg, Florida, U.S.

Designing the Swan-Elephant ashtray for Air India

Dali’s most celebrated connection with the country is a 1967 commission for Air India — The Swan-elephant ashtray. He designed limited edition ashtrays for the airline’s international first-class passengers.

The ashtray is mostly unglazed porcelain with a glazed serpent around the lip of the ashtray. It is supported by two surrealist elephant-heads and a swan. These supports are based on Dali´s double-image effect. The reflection of an elephant’s head looks like a swan and the reflection of a swan appears to be an elephant.

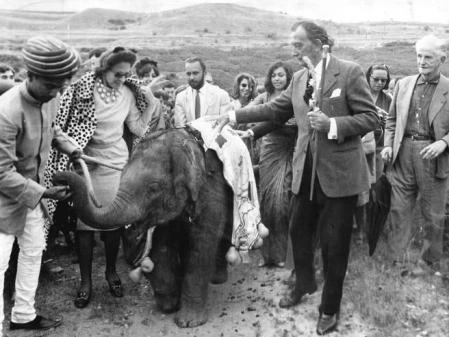

“For this artwork, he was remunerated with a baby elephant at his request,” says Christine. The two-year-old elephant was flown from Bangalore, accompanied by a mahout, to Geneva. The “big baby” as it was called, was trucked to Cadaques, Spain and cleared through customs. The Mayor of Cadaques had declared a three-day holiday to celebrate the arrival of the elephant. An Indian astrologer was flown from Bombay to take part in the festivities.

Ashtray designed by Dali for Air India

It was the first time that an artist of such world stature had designed an “objet d´art” for an airline. The unusual piece of art was presented to art lovers and friends of Air India globally. One such piece was also presented to Prince Juan Carlos of Spain (now King of Spain) in 1967.

It was in 1930 that Dali began developing his “discovery of the ‘double image’ effect through a ‘paranoia critical method’ by which, without the slightest figurative modification to its anatomy, an object can take on an entirely different appearance.

Dali’s India

Christine says though Dali never visited India, there are more links to India in Dali’s oeuvre.

Some of the sketches in the collection are based on photographs Pierre Argillet had taken during a trip to India in the 1970s, when the hippie movement was at its peak and young Americans visited India on spiritual quests.

Dalí’s India features elephants and temples but they’re not always easy to spot, having been rendered in the artist’s trademark surrealist style.

Dali with the baby elephant and its mahout after their arrival in Cadaqués, Spain

Dali, Pierre and Christine

Christine’s father, Pierre Argillet, was a great art publisher and shared a special bond with Dali. “He was Dali’s close friend. When he did not like certain works, Dali would tell him that the artwork was not for him and that he would do something different for him,” says Christine, adding that their relationship was unique.

Recalling the humorous side of Dali, she says once, when she was at the hotel Meurice in Paris where a crowd (of his admirers) had invaded Dali’s suite, the telephone rang. Dali’s secretary informed the genius that a lady wanted him to sign a petition against torture.

“A few minutes later, an unpleasant old lady came and told Dali to sign this petition against torture. A silence followed and then Dali replied “But Madame, I love torture” and she ran away from the room while the people had a hearty laugh,” recalls Christine.

She feels Dali was often misunderstood and his humour would sometimes give the contrary effect to what was expected. “Dali used to read a lot and when he was ready to work, he would do it at once, rapidly,” says Christine, adding that his personal life to his professional endeavours, Dali always took great risks and proved how rich the world can be when you dare to embrace pure, boundless creativity.

Christine Argillet

Respect for cultures

Christine says Dali had immense respect for all cultures to such an extent that when he married Gala in 1934, he took her to eight different places of worship. “In the late 60s, beginning of the 70s, Dali had this uncommon vision of a Western interest for the spiritual Eastern (the Hippy movement among them) and vice-versa, he would see the interest of Easterners for Western culture,” she says pointing out that this cross interest was new at the time and Dali would be fascinated by this encounter of both cultures.

Dali touched upon a wide range of subjects. He even wrote a cookbook and a book on wines (Les Diners de Gala and Les Vins de Gala), says Christine. Dali often met scientists and closely followed research on DNA. “Like Leonardo da Vinci, Dali was a complete artist.”

Dali’s artworks in Delhi

Speaking of the recently concluded exhibition, Christine says she was pleasantly surprised by the increasing number of visitors each day, collectors, artists, teachers with their classes, families. “It was very impressive. The visitors had specific queries about Dali and his art work, which demonstrated a great knowledge of contemporary art, which delighted me.”

Known for exploring subconscious imagery, Dali’s technical skills, precise draftsmanship and the striking images in his unusual pieces of artwork was a treat for the eyes.

The inquisitive visitors spent hours gazing at the intriguing pieces of artwork — human bodies sprouting flowers from their heads; eyeballs dancing in a matrix of squiggles and strokes and dismembered body parts interacting animatedly with the world around them.

“Some people visited the exhibition several times,” smiles Christine, who describes Dali’s collection on display as intimate. Artwork based on Greek Mythology, the Faust illustrations, the Poems of Apollinaire and the Hippies were among the most appreciated series of original copper etchings.

“This last technique, which Salvador Dali mastered perfectly, like Goya or Picasso, shows something more spontaneous, more immediate and which has to do with intuition, which shows the deep temperament of the artist,” she says.

Over the last two decades, large exhibitions have been organised across the globe which highlighted Dali’s diverse work. One was at the Los Angeles Museum of Art which displayed his work related to films L’Age d’Or and Le Chien Andalou by Luis Bunuel and Spellbound by Alfred Hitchcock.

Christine had a great time in New Delhi. “I made a habit of visiting an exhibition, a monument, a museum every morning,” she says, adding the rest of the time was spent at Dali’s exhibition.

ALSO READ: Waswo X Waswo: The ‘evil orientalist’ reviving Indian miniatures