(January 9, 2025) When Karsanbhai Patel, an unknown chemist from a small town in Gujarat began making soap in his backyard, selling it door to door on his bicycle on his way to work, Hindustan Unilever, then the reigning Indian giant, only scoffed at him. This soap was priced at Rs 3, and targeted India’s teeming underserved populations in tier 2 and tier 3 cities. The idea was absurd. Hindustan Unilever had ruled the market for decades, after all, with Surf, and sold exclusively to India’s monied elite. Then, in the 1980s, what remains one of India’s most iconic advertisements of all time, hit TV screens across the country. Doodh si safed,i Nirma se aaye Rangeen kapda bhi Khil khil jaaye, Nirma ne baandha sama, Washing powder Nirma…”

In what seemed like no time at all, Nirma took over the Indian market. And the bigwigs at HLL were forced to recalibrate. That marked the start of Operation STING (Strategy to Inhibit Nirma’s Growth), and the launch of Wheel. It worked, but it wasn’t Nirma. Patel had seen something that HUL had simply refused to acknowledge – the fortune at the bottom of the pyramid. In 2002, in his pioneering paper of the same name, co-authored with Stuart Hart, India’s foremost management pundit CK Prahalad would describe Nirma’s journey to becoming the largest selling detergent in India. In strategy + business, the colleagues debuted an idea that was both simple and totally radical: The four billion poor people around the world represented a vibrant consumer market that could be tapped with for-profit models. The poor, they said, need not simply be recipients of charity. They could be partners in profit. “The big challenge for humanity is to get everybody, not just the elite, to participate in globalisation and avail its benefits,” the Global Indian believed.

CK Prahalad

However, by the time the article was published in 2002, it had been rejected for four years by various scholarly journals, as the dominant idea at the time was that the poor were the problem of governments and non profits. It was too risky. What business structure could possibly support the penetration of goods and services to the remote rural corners of a country like India? Granted, these are still valid questions, but many companies did eventually hop on board. “The future lies with those companies who see the poor as their customers,” Prahalad predicted.

Global giants like Loreal and HLL began redesigning products that were affordable to the poorer classes, from shampoos to jams. The underserved populations had access to products they otherwise could not even have aspired to, and major companies found they had an eager, vibrant consumer base. CK Prahalad and Stuart Hill had transformed the way the world did business.

Early life

On his first day at convent school, six-year-old CK Prahalad and his brother went to greet the head mistress, who handed out a chocolate to Prahalad’s older brother, the taller and more handsome of the two. Prahalad waited for his turn, which never came. That evening, he went home and told his father, a judge and Tamil scholar, that he was not going to school. His father, an intelligent and progressive man, saw that his son was truly hurt, and the next day pulled both the boys out of the prestigious convent school. It was a risky move, as convent schools, where students were taught to speak in English, were the surest route to good colleges and jobs. Instead, the two boys were sent to a government-run Tamil medium school. It set the pace for CK Prahalad’s life, which would always be defined by radical ideas, risky decisions and informed by an unshakeable sense of ethics. The race for globalism, he maintained, should leave no man behind.

Through school, CK loved Physics, which he went on to study at Loyola College. He was all set to do his doctorate when his college principal told him that Union Carbide India was looking for a couple of interns. Until the Bhopal gas tragedy occurred in 1984, Union Carbide was one of India’s most prestigious companies.

CK would leave home at 4.30 am every day to get to his internship, which eventually turned into a full-time job. However, the factory floor was an unproductive place, manned by a highly highly unionized and unmotivated workforce. Disillusioned but driven to create change, CK stayed on and earned the trust of the other employees, before going on to address their challenges. By the time he left, his colleagues had accepted his recommendations. “You have to have the humility to go down to the lowest level and not be condescending. Until you actually experience what someone goes through, you should not judge them,” he would say later.

He also impressed his bosses, who sent him to Calcutta to meet the needs of the Indian army during the throes of the Indo-China war. Again, he found a system crippled by Communism, and his biggest challenge was to get through to the workers so he could get the plant up and running. Making people feel like they were part of the system too was the key to progress, he found, and appealed to their sense of patriotism. “Underneath it all is the same theme I was looking for when I was 19 years old: how to integrate the patterns of work with human motivation and excellence,” he told Strategy + Business in 2010.

A passion for management

In 1964, the first IIM had begun operations in Ahmedabad, Gujarat. CK decided to attend, although management was seen as an unconventional career choice in those days. There, he observed that Gujaratis were action and result oriented, unlike his fellow South Indians, who prized degrees and academic prowess over everything else.

He returned to Chennai, got a job at India Pistons, married and had two kids with his wife, Gayatri. He could have built a successful career in engineering, but had returned from Ahmedabad totally smitten by management. He applied at Harvard, and persuaded his wife to do the same. “We had no money at that time, we had two young kids and I said how are we going to manage? He said money is a resource, it’s not a constraint. If you don’t take this opportunity now it’s not going to come back again,” his wife, Gayatri recollects, in the book, CK Prahalad: The Mind of the Futurist. The couple graduated together, and CK had made history at Harvard Business School by finishing his doctorate in under three years.

To India and back

Again, CK Prahalad seemed to have the world at his feet. However, he was determined to return to India. Again, this seemed like a terrible idea – Harvard had offered him a teaching position and the Emergency had been put into effect in India. CK stuck with his decision, he wanted to begin his Impact India mission and taking up a job at IIM Ahmedabad seemed the best place to do so. It wasn’t mean to be. After the unbridled freedom he found in the US, CK was unable to deal with the slow, challenging bureaucracy of 1970s India. And he couldn’t deal with the idea of not making an impact.

However, a temporary opportunity opened up back in America, when a Professor at Ross Business School in Michigan University went on sabbatical. Friends and family questioned the wisdom of this decision but as CK put it, “Ideal opportunity is a rare thing and people get old waiting for it.” He was willing to take what he could get, and build on it from there.

He never forgot his homeland, though, and wanted, in some way to facilitate change. Unlike most economists and sociologists of the time, he believed that India’s population was an asset – it was a marketplace and a workforce in waiting. He also did not believe in socialism. “Let the world judge you for who you are,” he would tell his kids. “You have to make things happen on your terms.”

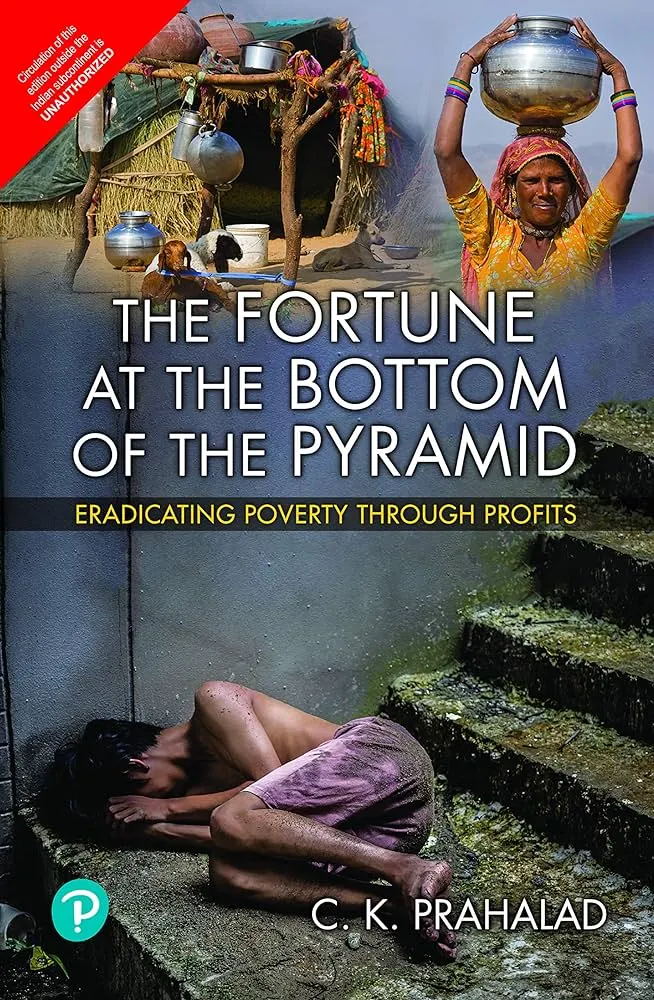

The fortune at the bottom of the pyramid

The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid is available on Amazon.

In the 1980s, CK noticed that a few small Asian firms were threatening the dominance of large MNCs in Europe and America. He began to research this, along with a doctoral student at University of Michigan, which resulted in his bestselling book, ‘Competing for the Future’. “Entrepreneurship is not about fit. Strategy must be about stretch.” It wasn’t about having all the resources of the world at your disposal, CK believed. “You can create resources, you can leverage resources.”

Through it all, the big question he toyed with was the one of global poverty. Management was a tool to turn things around, and CK was always concerned with how to enable the disenfranchised. He came up with the first draft of the Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid and submitted it to the Harvard Business Review, which promptly turned it down. The paper, they said, was simply too radical. Business was for the rich, the poor were the responsibility of the government. CK Prahalad and Stuart Hart suggesting that the teeming middle and lower classes were the world’s biggest market was simply too much for the conventional thinkers to accept.

It lay in waiting for two years before being published in Strategy+Business, a lesser known journal. It was turned into a book and continues to sell copies even now.

Crusader for India’s IT sector

All the while, one Indian titan had been following Prahalad’s work closely – Narayana Murthy, the co-founder of Infosys. In 1996, when Competing for the Future was released, Murthy invited CK to take a master class for a group of business leaders and CEOs in Mumbai.

This class, writes Paramanand, “was of historic significance to the Indian IT sector. It was the first attempt to appeal to the collective wisdom of Indian IT business leaders to project themselves in the global market as one force.” “Sell the India story first to global markets and all other marketing pitches could come later,” he said. CK advised Indian IT leaders to focus on the areas where global IT giants were weak, and to focus on enriching domain knowledge, rather than percentage of growth. “You have a chance to be world class from the beginning,” he said. “This is one industry where we have to be world class to even participate.”

In 2009, CK Prahalad was awarded the Padma Bhushan and the Pravasiya Bhartiya Samman. It was an acknowledgement that the management maverick had accomplished what he set out to do. Make an impact in India. And in the process, he also managed to change the world.

Read a similar story of Raj Echambadi, an Indian American iMBA pioneer.