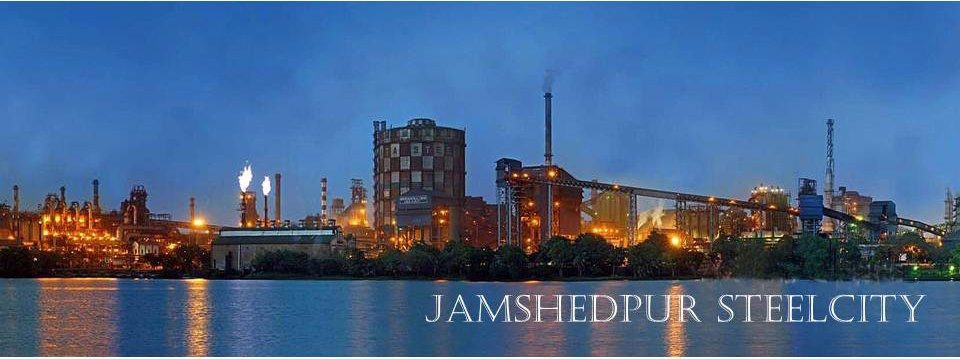

(July 16, 2021; 10 am) It was a regular September afternoon in the New York of 1902 when a strange man in a strange garb strode purposefully into a crowded office. He came to a halt at a table that was covered with books; behind those stacks was a man poring over account ledgers, a job he didn’t particularly enjoy. The seated man looked up with a start to see an Indian staring at him. What the stranger said next, changed the course of India’s corporate history. That stranger was Jamsetji Tata and the man poring over the accounts books was Charles Page Perin, a geologist and metallurgist, who went on to give shape to Tata’s dream of setting up a steel plant in India.

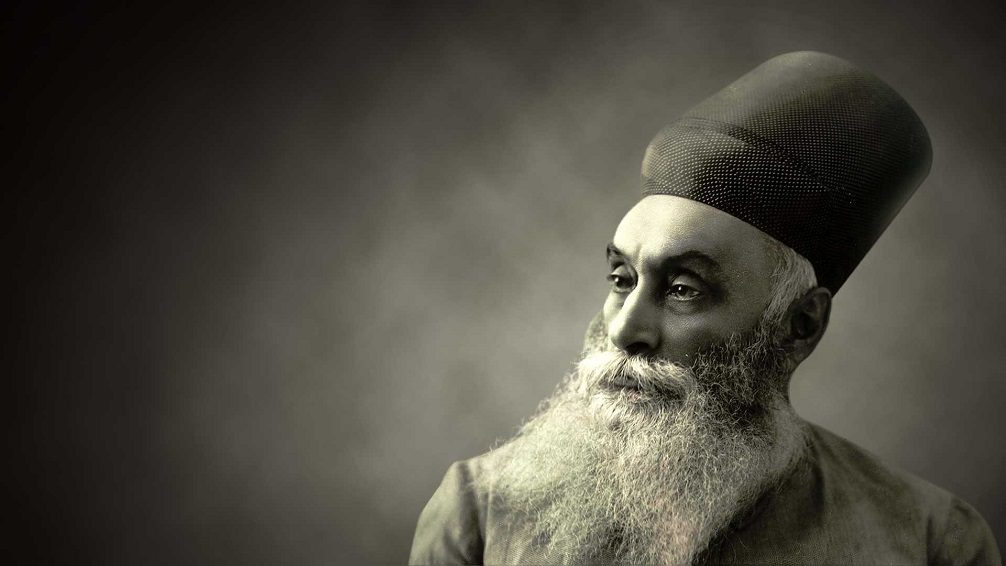

If there was one thing Jamsetji was convinced about, it was that steel production was of utmost importance for India’s development and progression. He relentlessly pursued the dream for years and even drew up elaborate plans. But he knew it was an ambitious venture not without its challenges. People were sceptical of Jamsetji’s dream; most famously Sir Frederick Upcott, the then chief commissioner for the Indian Railways. Upcott dissed Jamsetji’s plans saying, “Do you mean to say that Tatas propose to make steel rails to British specifications? Why, I will undertake to eat every pound of steel rail they succeed in making.”

Jamsetji Tata

Jamsetji was not one to be deterred. He knew that if he were to realize his dream, he would need the best talent and expertise on steel. In September 1902, disregarding his failing health, he set sail for the US which was home to the world’s finest iron and steel industry at the time. There he met Julian Kennedy, one of the best metallurgical engineers. Kennedy then pointed him towards Charles Page Perin, an eminent consulting engineer in New York, as the most qualified to undertake the geological work needed for a steel plant in India.

So, on that fateful afternoon, according to an article on Tata.com, Jamsetji met an unsuspecting Perin and asked, “Are you Charles Perin?” The metallurgist nodded. And Jamsetji said,

“At last, I have found the man I’ve been looking for. I have spoken to Mr Kennedy. He will build the steel plant — wherever you advise. And I will foot the bill. Will you come to India with me?”

As Perin was to recall years later, he was dumbfounded, struck by the character, the force, and the kindliness that radiated from Jamsetji Tata’s face. Perin’s answer was short, “Yes,” he said, “yes, I will go with you.”

From New York to India

American metallurgist Charles Page Perin

Born in 1861 at West Point, New York, Perin was the son of army officer Glover Perin and Elizabeth Spooner (Page) Perin. After graduating from Harvard in 1883, Perin continued his studies at École des Mines in Paris for a year. He then began his career as a metallurgist and later superintendent at a small mine in Massachusetts before working as a general manager for several mining, steel, and railroad companies in the US and Canada.

By 1900 he had opened a consulting office in New York where one of his first assignments took him to Siberia in the winter to search for coal supplies for the Trans-Siberian Railroad.

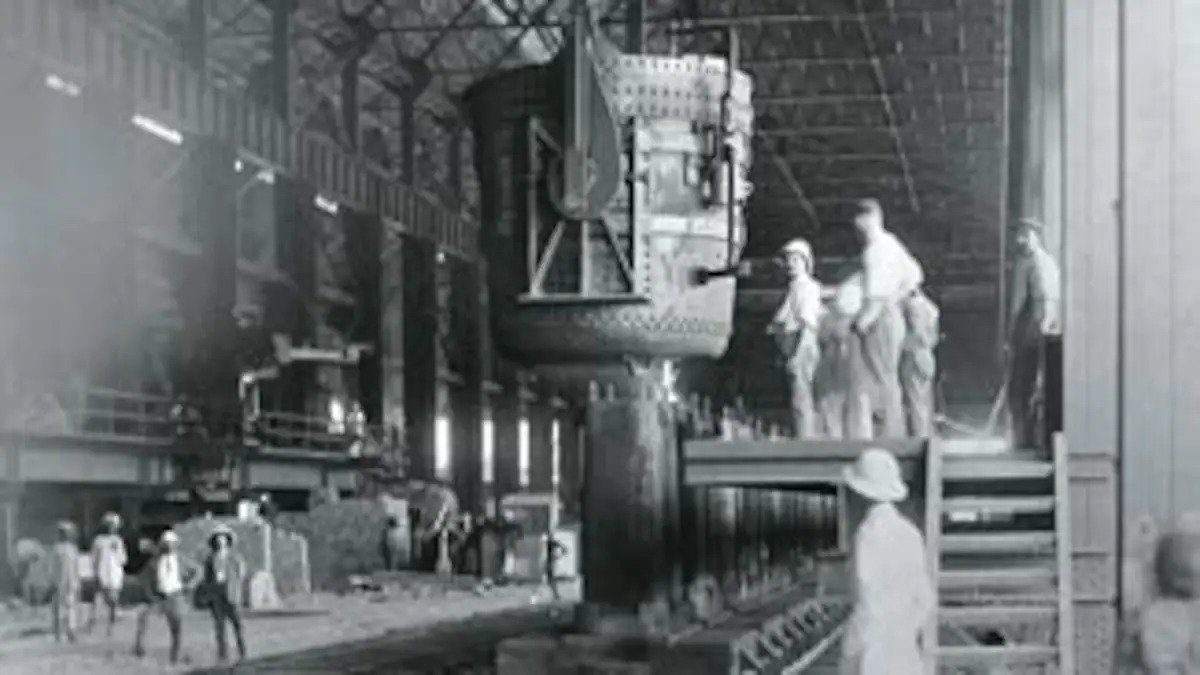

Giving shape to a dream

In 1902, he was roped in by Jamsetji to work on his ambitious iron and steel plant and Perin set sail for India, one of the most unusual adventures of his life. While he was on his way, he received a telegram asking him if he could ride a bicycle. He was stumped at the question, but replied that he could. When he reached the village of Sakchi (now Jamshedpur) he discovered the reason behind the strange telegram. There was no motorable road for miles; no conventional mode of transport could take him to his destination. He found himself pedaling a bicycle for several strenuous hours and found himself in the middle of the jungle till a passing bullock cart rescued him.

There were many more hurdles for him to deal with: the land was harsh and demanding, temperatures extreme, man-eating tigers and road elephants to deal with, and cholera and malaria would sweep the hillside causing workers to flee overnight. But it was here that Perin found more than he and his team had dared to hope for: around 3 billion tons of ore, just 45 miles away from the railway station.

The Tata Steel Plant

Drawn by Jamsetji’s indomitable spirit, Perin worked willingly in the most far-flung places such as Dhalli and Rajhara hills. He helped Jamsetji’s son Dorabji Tata and cousin RD Tata establish Tata Steel in 1907, four years after Jamsetji’s death. When the company faced initial difficulties with its open hearth furnaces, Perin help resolve them too. By 1912 the first ingot of steel successfully rolled out of the Tata plant; it was of the finest quality. And it was all because of the American metallurgist who followed Jamsetji to the other corner of the world to help him chase his dream.

Editor’s Take

Today, Tata Steel is one of the top steel producing companies in the world and the Tata Group itself has spread its branches much like a Banyan tree. But India was a different place in 1902 and can imagine how many naysayers would have dissuaded Perin from journeying to India. The story of the lone American metallurgist who decided to follow a man who inspired him to the ends of the world and work under extremely inhospitable conditions needs to be shared in business schools. One has to admire Jamsetji’s conviction in selling his vision to Perin. It tells us that leadership is all about finding the right man for the right job, even if it means handpicking someone from another continent.

- RELATED READ: Jamsetji Tata was the world’s top donor of last century