(July 29, 2022) Sitting on the sofa at home and helping his grandmother take dozens of medications every evening to treat her chronic asthma is one of the earliest memories that shaped Syamantak Payra’s outlook on life and his desire to help. Desperate to help, he invented a makeshift breathing machine “out of some straws and balloons” at age four. “It was rudimentary and practically ineffectual, but it came from the same motivation that still drives me: I saw a problem, and I wanted to help,” says the 2022 Hertz Foundation Fellow.

From the same desire stemmed the idea of developing a knee brace that helped the inventor and researcher win the Intel Foundation Young Scientist Award in 2016. “I want to help people. Whether that’s by creating new biomedical technologies that will improve patients’ prognoses, or through literacy outreach that will help create new opportunities for young students, I wish to use my capabilities in the ways that I will best be able to help empower others,” he tells Global Indian.

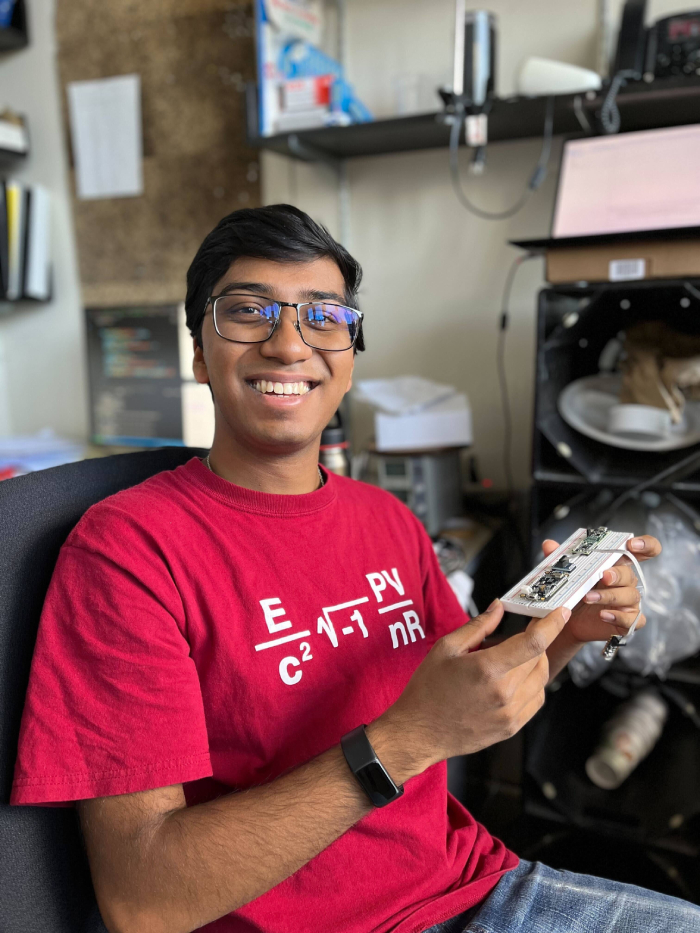

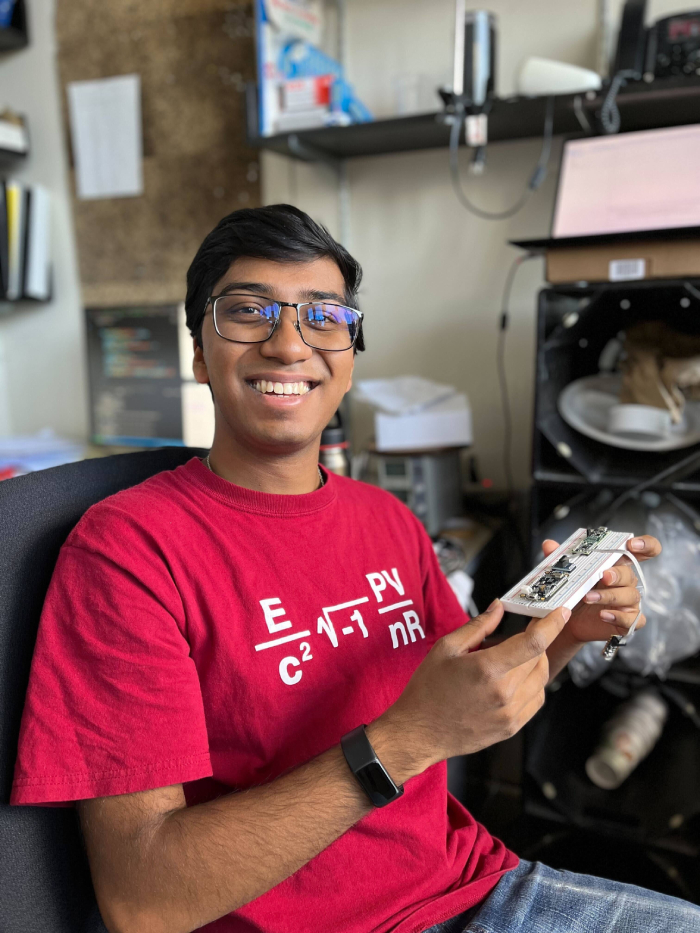

Syamantak Payra

Curiosity, science and innovations

Growing up in Houston, a stone’s throw away from Johnson Space Centre – headquarter for many NASA operations, Syamantak would spend endless afternoons enquiring about the workings of the world from his Bengali grandfather. Curious to know “why the colours in rainbows appeared in that order or how car engines and sewing machines worked or why leaves on trees didn’t all blow the same way”, his inquisitiveness was embraced by his parents, grandparents, and later, teachers. As early as Grade one, he began completing his scientific projects which helped him tiptoe into the world of science “as a method of inquiry.” Over the years, it translated into a love for the subject and many scientific disciplines including “materials science and the physics of photovoltaic cells and biomedical engineering and robotics.”

The following years of experimentation, discoveries, and innovations culminated in his first breakthrough in 2016 when the inventor won big at the Intel Science Fair for developing a knee brace that can help individuals partially disabled by polio to walk swiftly. For someone who always “wanted to help”, he was inspired to take on the project after learning about his teacher’s polio-led partial paralysis. “I was interested in robotics, and wanted to try to use robotics to help restore some of his capabilities: effectively creating a robotic leg brace that would allow him to walk with less effort and pain,” says the inventor who revised and built his prototypes for over two years.

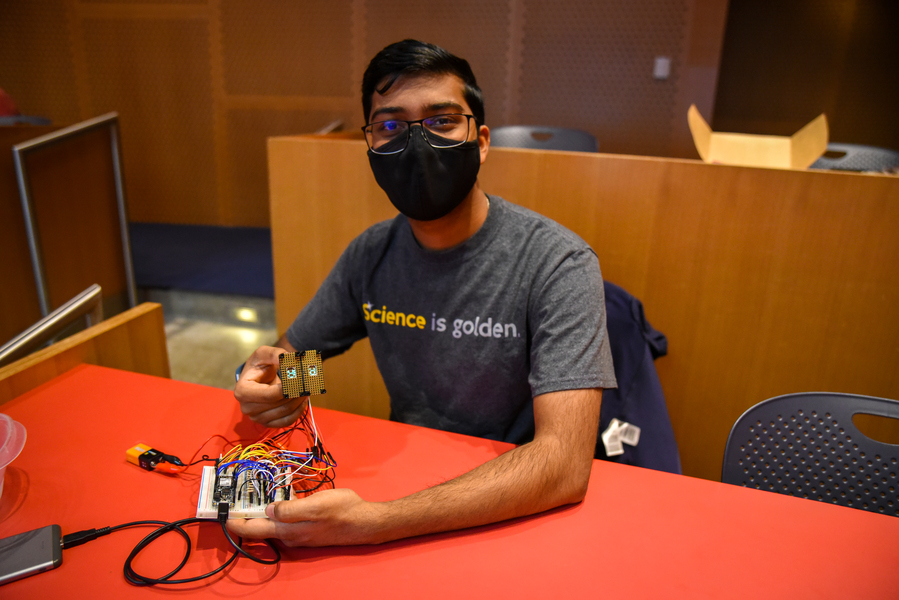

Syamantak Payra showcasing one of his inventions

The power of innovation to transform lives

With no prior experience in programming or biomechanics, the project was nothing short of a “self-guided crash course” for him. “I pored over hundreds of papers analysing prosthetics and anatomy, developed my data equipment and analysis methods, and had my teacher try on the prototypes to evaluate their functionality. My revised version of the robotic leg brace was able to restore nearly 99 percent of his knee mobility, and allowed him to walk with 33 percent less effort,” adds the inventor.

As someone passionate about research, Syamantak is “excited about the potential for innovation and the power it holds to create transformative new technologies” to create positive impacts in the world. Keeping up with his quest to find solutions that create a ripple effect, he made some interesting innovations during his bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering and computer science at Massachusetts Institute of Technology – one of which is digital fibers for electronic garments that can assist in diagnosing illnesses. Explaining his work in the MIT Fibres Group, he says that it has enabled them to “create polymer threads with microchips embedded within the fibers. These fibers can then be woven into fabrics that contain those microchips directly within the textile.” A technology that took over four years to develop, he says, helps create fibers that are capable of sensing, computing, and communicating, such that worn garments will be better able to assist in monitoring, diagnosing, and treating health conditions.

The impactful work

The years at MIT turned out to be fruitful as he ended up making prototypes like temperature detecting shirts that could detect heatstroke and potential dehydration to making spacesuits that help improve astronauts’ situational awareness and their safety on spacewalks. “The spacesuits worn for spacewalks must be pressurised against the vacuum of space; one side-effect is that if something touches or impacts the spacesuit, it is difficult for the astronaut to feel it. In addition, spacesuits are constantly bombarded by space dust, particles that can travel at thousands of kilometers per second and significantly damage textiles. By incorporating sensors and advanced electronics into the spacesuit construction, we can imitate different sensations and reproduce them on the skin,” he beams with pride.

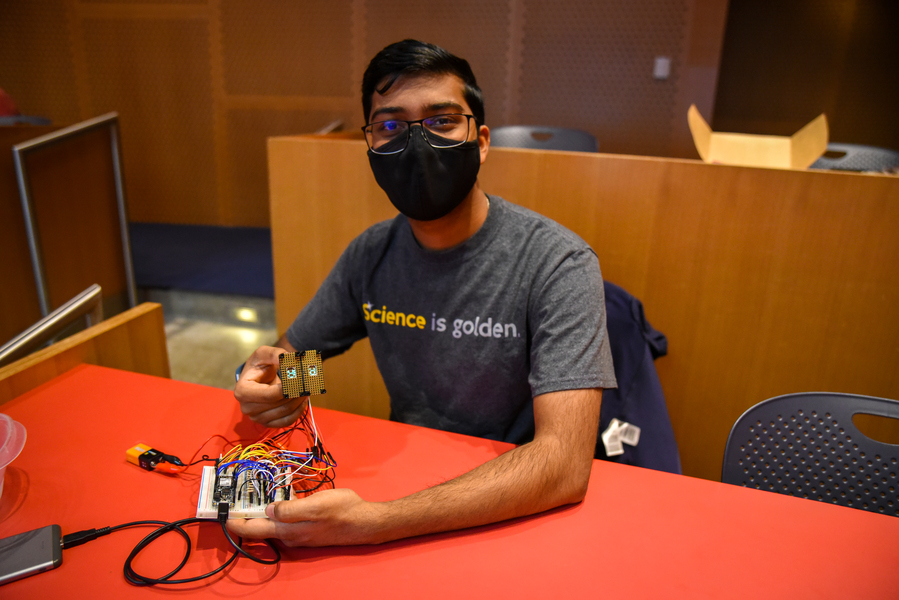

Syamantak in a Nanotechnology class at MIT.

Having walked the corridors of MIT for years and creating some stellar innovations, it holds a special place for Syamantak – as it not only honed his skills as an engineer and a scientist but also as a community leader. “Crucially, it’s shown me how the most important part of engineering isn’t the blueprints, it’s the people: who will use something, how, and why.” The Paul & Daisy Soros Fellowships for New Americans recipient is now gearing up for a PhD in engineering at Stanford and aims to create “new biomedical technologies that can interface more closely with the body and help us address exactly those gaps in healthcare: difficult early diagnoses, complex monitoring in-vivo, and careful post-treatment care.”

A community leader

But it isn’t just his innovations through which Syamantak is creating ripples in society, his zeal for literacy and STEM has helped him extend help to the underserved children in Houston. A spelling bee champ through his middle school, he was keen to share his love for the language and started literacy workshops sharing spelling and vocabulary lessons to young students for which he received the Presidential Volunteer Service Award for outstanding commitment to education twice. Moreover, he launched a STEM outreach program (CORES) at his high school called CORES which has now expanded to more under-resourced schools. “At MIT, I was also part of a group called DynaMIT; every year, we host a summer program aimed at helping underprivileged students in the Boston area gain exposure to STEM fields through experiments and activities that they wouldn’t have experienced within their schools.”

This desire to make an impact helps Syamantak push the envelope with each of his innovations. Years of working in the field have come with their share of learning, and the one that has made the 21-year-old humble is that “part of the joy in scientific research is the discovery that comes from unexpected connections.” The Bengali lad loves poetry, so much so that he spent hours learning Rabindranath Tagore’s songs and poems while growing up, and is now a published poet. A strong believer in the power of music, Syamantak plays violin and piano, produces classical and modern music, and is an avid photographer. “I view the world through a camera lens: filming wide landscapes from aerial drones gives me a sense of perspective, and photographing minuscule wildflowers with a macro lens lets me connect intimately with the smallest details of nature,” he says.

Having received many fellowships and awards including Hertz Foundation Fellowship, the Paul and Daisy Soros Fellowship for New Americans, the Stanford Knight-Hennessy Scholars Program, and the Astronaut Foundation Scholarship, Syamantak feels grateful for them as they have been instrumental in supporting his academic pursuits by funding his studies, he says. However, for him, the ultimate validation would be to create a direct impact on the lives of people with his work. “If I can improve someone’s quality of life, or aid a patient in their treatment or recovery, that is the most direct validation that I have been able to make a difference through my work,” he signs off.

- Follow Syamantak Payra on Linkedin