(December 1, 2023) Five years ago, Atreya Manaswi was on a fishing trip with a friend and his grandfather. The friend’s granddad, who was an experienced beekeeper, was entertaining the two eleven year olds with stories about his bees. “He was telling us about how, decades ago, he would get dozens of barrels of honey and how that season, he’d gotten merely three,” Atreya told Frederick Dunn, Cornell University’s Master Beekeeper, in an interview. “He was describing this almost tearfully.” Atreya was so moved by the story that he came home and began to do some research. It was the start of a new interest and profound breakthroughs for the young scientist. Five years on, the young Global Indian, who began his university-level research at the age of 12, has a slew of awards to his name, the most recent being the Barron Prize 2023.

Now an eleventh grader at Orlando Science High School, Atreya has been conducting research in collaboration with the US Department of Agriculture and the University of Florida since the age of 12. He has developed a novel, eco-friendly, low-cost organic pesticide that acts against small hive beetles and varroa mites, some of the leading causes of hive collapse and the decline in honey production. He is also the author of The Bee Story, a children’s book about bees, environment and agriculture, meant to raise awareness about the pollinator crisis. That apart, Atreya is an active public speaker and has spoken at numerous international conferences, with the support of the UN and the World Food Forum. He is a Top Honors Awardee at the BioGENEius Challenge US, made it to the top 30 at the Broadcom MASTERS, won third place at the Regeneron Pharmaceuticals & Society for Science and is a published author in the Journal of Applied Entomology.

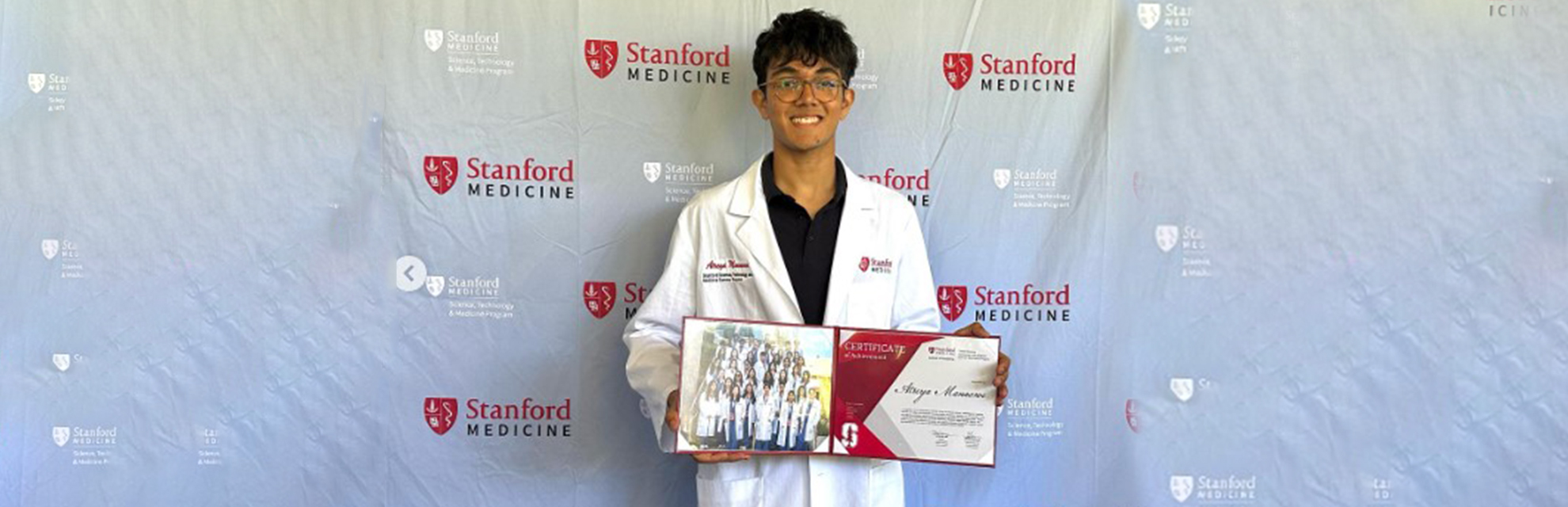

Atreya Manaswi

A young researcher is born

Atreya’s research led him to the South Florida Bee College‘s bi-annual conference, where he first crossed paths with Dr Jamie Ellis, a world leading entomologist. “That’s where things really took off and I began my honeymoon research journey,” he says. Dr Ellis would go on to become his first mentor. “After the seminar, I went up and asked him a question and we started speaking,” Atreya recalls. He made an elevator pitch, daunting as it was for an elementary school student to approach a world class scientist. His other mentor is Dr Charles Stahl, at the US Department of Agriculture, and his ninth grade Chemistry teacher, Mrs Bright, he says.

Born to scientifically-inclined parents in Gainesville, Florida, Atreya’s interest in STEM had been encouraged right through his childhood. His father is a physician and he was exposed to science always. “My parents would buy me chemistry kits and tools to play with, like different skeletons I could put together, and Legos, that fostered my interest in science,” he said. Although he didn’t get early access to labs, he learned early on how to use the cold call approach, which worked out well for him with Dr Ellis. “That’s what the real world is like,” Atreya remarks, showing remarkable wisdom for his age. “Nobody is going to hand you an opportunity.”

Atreya’s work and his elevator pitch impressed Dr Ellis, who invited him to take a tour of his labs at the University of Florida. That’s where Atreya’s own research began, really. During his first year, at the age of 12, he studied nutrition management with pollen substitutes. It was a laboratory study, with ten honeybees in ten different cages. “I was looking at different diet substitutes that can be given by beekeepers where there is a dearth of pollen or if the pollen isn’t diverse in the natural environment,” he explains. He experimented with wildflower pollen and three forms of commercially made substitutes to see what the bees preferred. He found that the bees preferred wildflower pollen, followed by a substitute called AP 23. He went on to co-author a research paper with his team, which included Dr Ellis, which was peer reviewed and then published in the Journal of Applied Entomology.

Researching hive beetles

In his second year, he began studying hive beetles, which colonise the hives. Found in over 30 states in the US, mostly in places with warmer, more humid climates, these tiny beetles eat and defecate in the hives, leading to the fermentation of honey and in extreme cases, force the bees to abandon the hives completely. There are plenty of treatments available but many are chemical-based. “These chemicals pose a severe risk to wildlife, aquatic organisms, honey bees and humans – and are also extremely expensive, costing anywhere between USD 16-22,” Atreya says. Moreover, traces remain in the honey, the wax and the royal jelly, which are either eaten by humans or used in the pharmaceutical industry.

Atreya decided to look into organic substitutes. Apple cider vinegar is the most popular option among beekeepers but is also fairly expensive, leading to very high costs for beekeepers with large apiaries and several hives. “We tested seven organic agents in the form of field trials,” he says. “I got stung a lot, and I learned about the hardship and determination that goes into beekeeping. Atreya and his team used seven organic agents – yeasts, scented oils like peanut, grapeseed, cantaloupe puree, mango puree and beer. “They are all odorous, basically. And our control was apple cider vinegar,” he says. The beetles are naturally drawn to these substances and are known to feed on sap and rotting fruit. The strategy was to use things that the beetles like, making it easier for beekeepers to lure and trap them.

The beer-loving hive beetles

What they found was transformative. The beetles loved the beer – they had used Miller’s High Life because it was inexpensive and readily available. In fact, it worked several times better than the control, apple cider vinegar. “That was the second year of research,” he said. “Then we worked to refine that.” Beer is up to 95 percent water, and a lab made concentrate would be far more effective. So they got to creating a synthetic blend, that was affordable and also attractive to the beetles.

The process is fascinating. It involves a polymer resin placed in a glass tube, which is attached to a vacuum and placed in a beer bottle. “Air from the beer container is pulled and trapped inside the polymer,” Atreya explains. The chemicals trapped on the polymer are then analysed and “the compounds that weigh less are selected.”, he says, adding, “Then we take beetles under a microscope and extract their antennae. The antennae can function on their own for up to five minutes and were made to respond to different chemicals on a forked electrode. “The electrode picks up what they’re sensing. It’s very interesting and fun to try in the lab,” he smiles. The beer was 33 times more effective than apple cider and the blend they created is only half the cost of the best known chemical substitute.

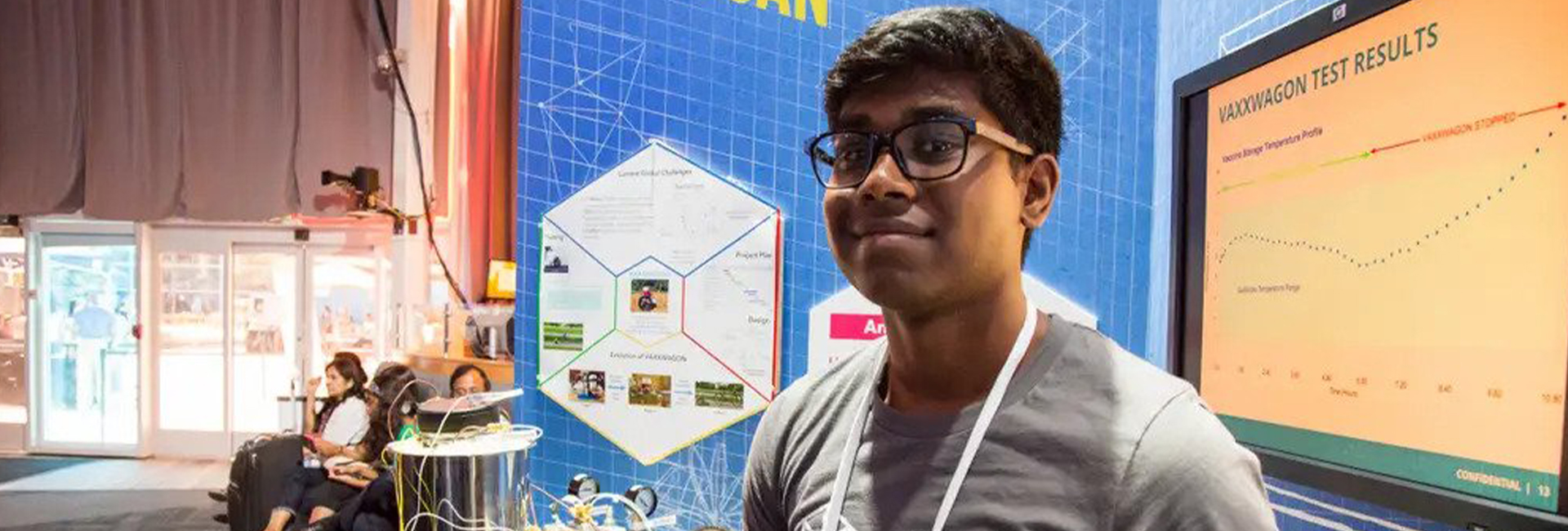

Finding recognition

It’s game changing research, and since it could provide beekeepers everywhere with cost-effective, eco-friendly solution to a significant problem, Atreya’s work has generated a lot of interest. At the International BioGENEius Challenge US, where he was named the Global Highest Honors Awardee, Atreya interacted with other brilliant young researchers as well as top pharma companies who set up stalls and scouted for talent. He’s a regular in the STEM competition circuit in the US and Canada, which comes with a lot of benefits, apart from substantial cash prizes. “The most important thing is the critical feedback you get at the regional and national levels,” Atreya says. “There’s also recognition and building a great network, it’s an inner circle of like-minded people.” Learning to take feedback, he says, is the most important thing. “If you can’t do it, you won’t get better.” It’s vital, he says, because at the national and regional levels, everyone is so exceptional.

All this and Atreya Manaswi is still only in the eleventh grade. When he’s not studying bees, he practices Taekwondo and holds a second degree black belt. “I also really enjoy theatre,” he says, adding with a smile that he enjoys antagonistic roles! He has also started a non profit that conducts workshops on STEM learning for students in local schools. “My aim is to host an international workshop for students around the globe, focussing on different STEM topics, tools and technologies,” he adds.