(July 8, 2022)

Staying in a run-down hotel in Tripura, near the Bangladesh border, with very poor connectivity, Shivakshi Bhattacharya was surprised to receive an early morning call from Canada. Expecting it to be a spam call, she answered to hear a woman’s voice at the other end, saying, “Congratulations!” Shivakshi was officially a Schwarzman Scholar 2023 – news she received with a shocked, “Are you sure?” Yes, they assured her, they were sure, she was doing “incredible work.” At the end of July, Shivakshi will join a small, very elite group of Indians who have had the opportunity to do a year-long master’s in global affairs at Tsinghua University in Beijing.

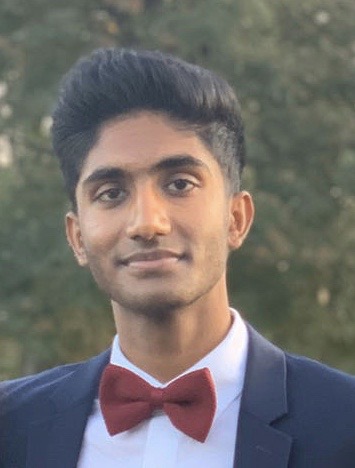

“It’s been a tumultuous journey,” Shivakshi sighs, as she calls me on a rare day off. The 26-year-old lawyer has founded numerous organisations that work with women – something she began in 2014 – as a law student. Despite having doctor parents, she decided against a career in medicine herself, because she “wanted to be in the impact sector,” she tells Global Indian. Today, she runs The Laali Project, teaching entrepreneurship skills to girls from rural areas. Shivakshi is also a campaign manager in Bihar for Prashant Kishore’s IPAC, a heavy-duty assignment, it seems, for it keeps her days full. She has also spent two years as a Teach for India fellow in Tughlaqabad, Delhi.

As the founder of the Hunkaar Foundation, Shivakshi has been instrumental in providing rural women access to high-quality, affordable sanitary napkins, with a business model that helps them work towards financial freedom. Her first initiative, Make India Bold, worked with spreading awareness among schoolgirls on issues like sexual harassment and abuse, impacting thousands of students in rural Haryana, Madhya Pradesh and Jammu and Kashmir.

Shivakshi Bhattacharya. Photo: Instagram

Taking on the system

Shivakshi Bhattacharya spent her early years in Nepal, where her parents were deputed. She returned to India in time for grade eight, “because of the political struggle schools were shut, buses were being burned and there were strikes.”

Her moment of reckoning came on her first day of law school in Haryana’s Sonipat district in 2014. Not long after arriving at one of the country’s top institutions – home to one of the most elite student bodies – Shivakshi dealt with sexual harassment from a fellow student. She posted about the incident on the college social media page and found support among several women who faced similar behaviour by the same student. She decided to fight, becoming the first person to file a case since the school opened in 2009. “It’s very sad, more so since it’s a law school where you’re supposed to create an open and safe space for students.”

Shivakshi soon found that fighting a case, even in such a progressive and top-tier institution was a traumatic experience. Authorities were hostile, and as were her fellow students, including women. “People went so far as to ask if I was making a complaint to get attention.” She recalls men walking up to her to remark, “‘Hey, Shivakshi, if we talk to you, will you file a complaint against us?’ But this was the start of my journey.”

The case was resolved, albeit unsatisfactorily, with the perpetrator being handed the minimum punishment. Still, the University decided to set up a committee to hear complaints of sexual harassment. And as she struggled against the system, Shivakshi decided to work with school children and spread awareness about how to counter the various ills that plague our society.

Make India Bold

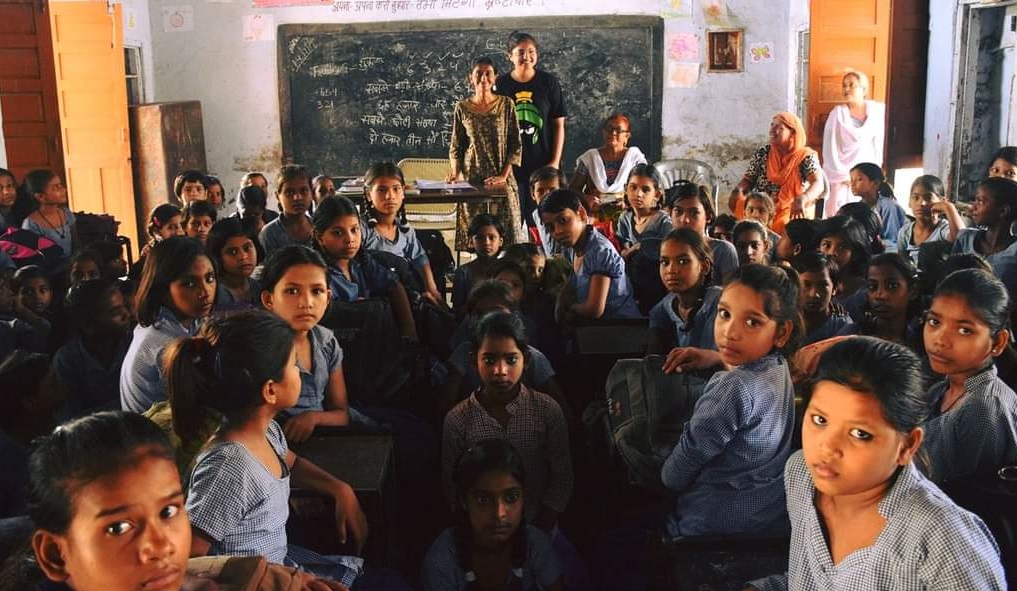

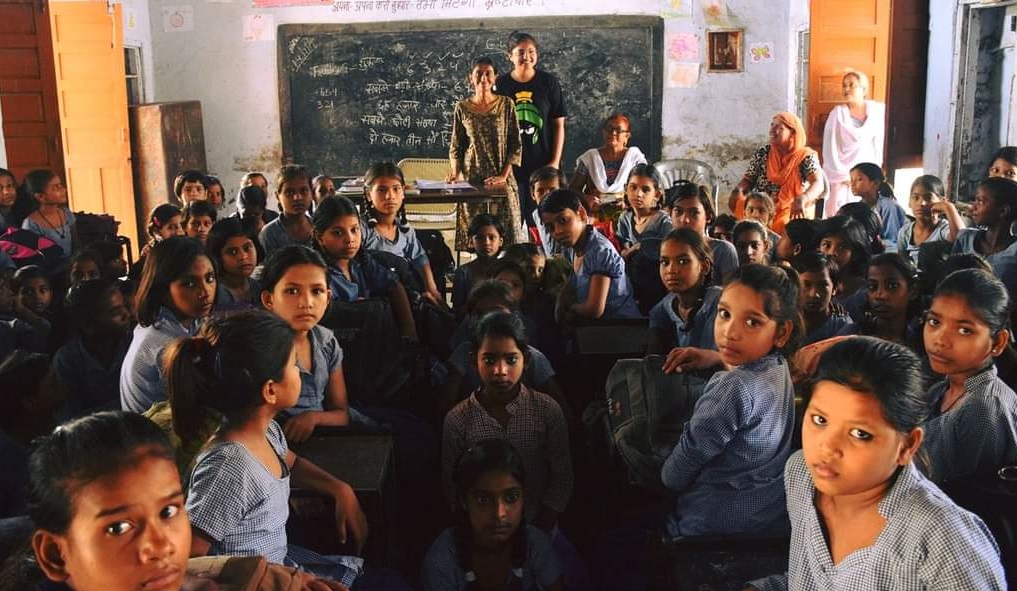

Worn out but undefeated, Shivakshi Bhattacharya visited a friend’s place in Madhya Pradesh, where the latter had contacts in educational institutions. During their morning rounds to visit schools, they discovered the whole gamut of issues, from bullying and neglect to abuse. With a framework of information behind her, she returned to Haryana for college and began working with the 139 villages that surrounded her University town, focusing on private and rural schools.

“The methodology varied but the problems were more or less the same – scandalous videos, sexual abuse, casteism and classism,” Shivakshi says. Surprisingly, the caste divides were greater in private schools than in their rural counterparts. “I had a very biased picture, I assumed that there would be more caste-related problems in rural schools.” Irrespective of whether the school was private or rural, most children had no idea what sexual harassment meant, how to detect problematic behaviour or how to report it. Most weren’t even aware of the child helpline.

Believing that early intervention is key, Shivakshi and her team formulated different training modules – for grades one to five, six to eight and nine to twelve. The programme was a roaring success, almost instantly, with some 500 students in attendance for the first session. Over the next year-and-a-half, Make India Bold impacted up to 30,000 students in and around Sonipat district. “We started getting offers – the Shiv Nadar Schools reached out to us and we signed an MoU with the Haryana government that gave us access to government schools as well,” Shivakshi says.

“Being able to talk to so many people who had suffered for years – the energy drove me. I kept knocking on people’s doors, going to the Ministry of Women and Child Welfare every day for 15 days.” It was a “bottom-up approach,” starting with the students, and then moving up the ladder. In 2015-16, during an internship with the Ministry of Education in Kashmir, she gave training sessions to school principals as well.

Hunkaar Foundation

As she did the rounds of Haryana’s villages, visiting anganwadis was a routine part of the agenda. Most were shut. In one village, Shivakshi Bhattacharya met seven women who had been shunned by the community for undergoing hysterectomies. “They were a group of about 28 women who had become destitute because they couldn’t bear children,” Shivakshi adds.

It led her to consider working with menstrual health in rural areas, an idea that would become the Hunkaar Foundation. The organisation used a microfinance model and collaborated with a biodegradable napkin manufacturer, who helped bring in imported napkins from Korea, for ₹18 instead of ₹85.

After an early round of fundraising for seed money, the Hunkaar Foundation procured the first batch of sanitary napkins which were given to a group of seven girls, who had to drop out of school after they reached puberty. “We wanted to ensure some degree of financial independence for them,” Shivakshi explains. The girls sold the napkins and cultivated a source of income, while the fathers and brothers couldn’t object as “the customers were women and the girls didn’t have to leave their homes.” Her seed fund was returned in full six months later and was taken to the next village.

Staying true to her working model, Shivakshi sets up the process and then steps away. “I want to work on multiple things and besides, these projects belong to the people for whom I started them.”

With 30 women across different villages, hundreds of girls have access to affordable, high-quality sanitary napkins. Another, unintended consequence was the restoration of anganwadis in Sonipat district. “When we first arrived, they weren’t functioning at all.” They filed multiple petitions under India’s Right to Information (RTI) Act, to no avail. However, the children of the now-empowered women began using them as places of learning.

The Laali Project

Although emboldened by the success of the Hunkaar Foundation, Shivakshi Bhattacharya understood that menstrual health is one piece in a much larger puzzle. “I also understand that change is incremental,” she remarks. “You can’t walk in to a village as an alien and tell them to change the way they live. Instead, we enable them to create the change themselves.”

So, The Laali Project was founded, aimed at bringing entrepreneurship models to students. The foundation works with 15 organisations and has also partnered with the Child Support Initiative, Nigeria and Unity Effect, Germany . “I made training a curriculum objective,” she says. The training has a multi-pronged approach – menstrual health, gender sensitisation and sex education make up one module, social and emotional learning is the next. Entrepreneurship skills are a section on their own and include lessons on design thinking and soft policy skills.

The pilot project was run in collaboration with Goonj, a Delhi-based NGO that undertakes disaster relief, humanitarian aid and community development. “The founder, Meenakshi ma’am, helped me a lot,” Shivakshi says. Before she logs off, she makes special mention of one of her most cherished outcomes: “Four grade nine students have their own organisation – a learning centre where they teach men about menstrual health. The founder was the shyest girl in class, afraid to even say a word when she first came in. Today, she’s teaching men.”

- Follow Shivakshi on LinkedIn