(November 2, 2022) A chance visit to a market in Mumbai during her India trip some four years led Anika Puri to a shocking visual – rows of ivory jewelry and statues. For decades, the ivory trade has been illegal globally, and elephant hunting is prohibited in India since the 70s. However, coming across a market that had unabashedly displayed ivory products took Indian-American teens by surprise. “I was quite taken aback. Because I always thought, ‘well, poaching is illegal, how come it is still such a big issue?” the New York resident told Smithsonian Magazine. The revelation changed her outlook towards poaching and led the innovator to invent a device that could spot elephant poachers in real time with 91 percent accuracy.

That visit to the Mumbai market led Anika to research and look up statistics on the internet, and the results were startling. She learnt that Africa’s forest elephant population declined by 62 percent between 2002 and 2011. Not just this, the rapidly diminishing habitat and pressures from human activity have had a dramatic effect on the elephant population in India. In 2017, the Union Environment Ministry reported that there were 27,312 elephants on average in India, which was a decline from the 29,576 elephants recorded as the mean figure in 2012. She knew that she had to do something to protect the species from poachers.

Anika Puri invented ElSa to spot elephant poachers in real time

Though drones are currently used to detect and capture the images of poachers, Anika realised that they aren’t accurate enough. It was after watching a handful of videos of elephants and humans that she noticed that the two differed vastly in terms of their movement, especially their speed, their turning patterns, and other motions. “I realised that we could use this disparity between these two movement patterns to increase the detection accuracy of potential poachers,” the innovator added.

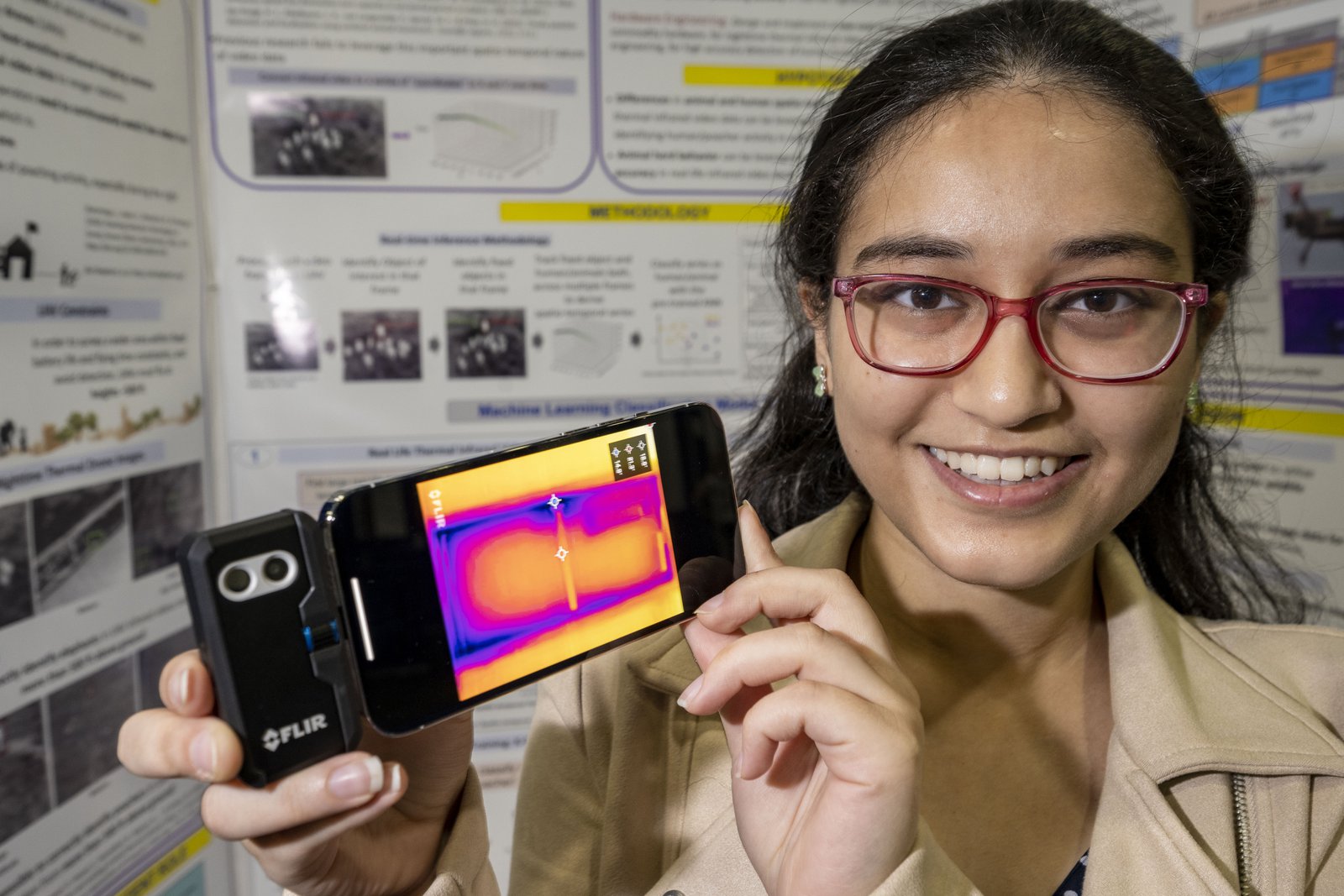

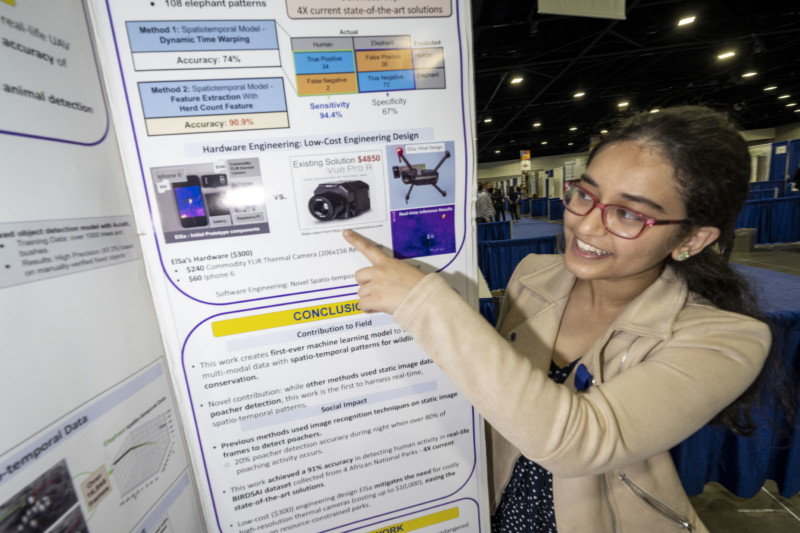

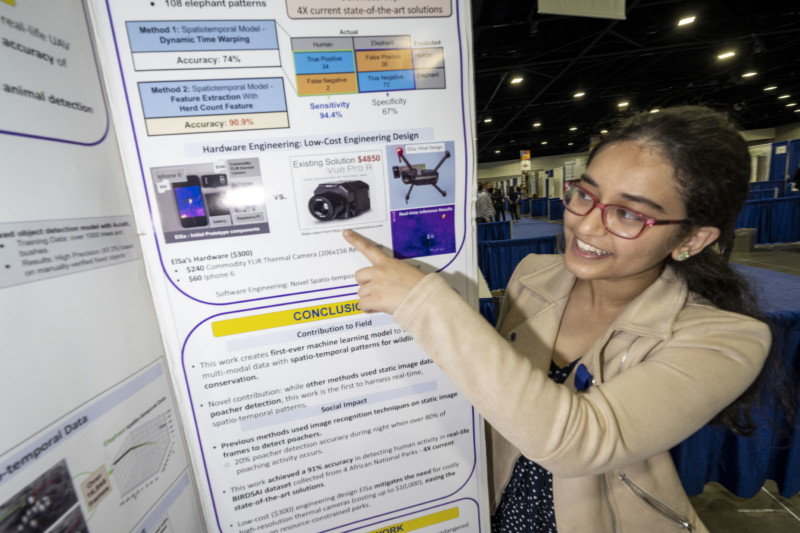

This initiated a two-year-long journey of building ElSa (Elephant Saviour), a low-cost prototype of machine-learning software that can observe and analyse the movement patterns of humans and elephants in thermal infrared videos. The Indian-American teen says that ElSa is four times more accurate than the existing detection methods, and its software is even compatible with low-cost cameras, thus eliminating the need for high-resolution thermal cameras. So how does it work? She revealed to the magazine that ElSa uses a $250 FLIR ONE Pro thermal camera with 206*156 pixel resolution that plugs into an off-the-shelf iPhone 6. The camera and the iPhone are later attached to the drone, which helps the system produce real-time inferences as it flies over wildlife parks identifying if the objects below are humans or elephants.

Anika Puri won the Peggy Scripps Award for Science Communication

This project led her to the 2022 Regeneron International Science and Engineering Fair, the world’s largest international preschool STEM competition, and also won her the $10,000 Peggy Scripps Award for Science Communication. The Global Indian was thrilled and honored to share the stage with teens who “enjoy science and research.”

It was right after her ninth grade that her love for artificial intelligence blossomed when she was selected for Stanford AI Lab’s summer program. Her initial enthusiasm was based on AI’s “limitless possibility for social good” but she soon discovered that since data is collected and analysed by humans, it does contain human biases. “It can reinforce some of the worst aspects of our society. What I realised from this is how important it is that women, people of color, all sorts of minorities in the field of technology are at the forefront of this kind of groundbreaking technology,” she added. As a result, she founded a nonprofit mozAlrt, a nonprofit which inspires girls and other underrepresented groups to get involved in computer science using a combination of music, art, and AI.

During one AI conference, Anika met Elizabeth Bondi Kelly, a Harvard computer scientist, who was then working on a wildlife conservation project using drones and machine learning. The teenager approached her with the idea of catching animal poachers using movement patterns, and soon Kelly became her mentor for the project. It was under her guidance that Anika started working on the prototype which the innovator says has 91 percent accuracy.

Anika, who is currently studying electrical engineering and computer science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, has plans to expand her movement pattern research to other endangered animals, including rhinos. The innovator is keen to implement her software in national parks in Africa.

that was so cool